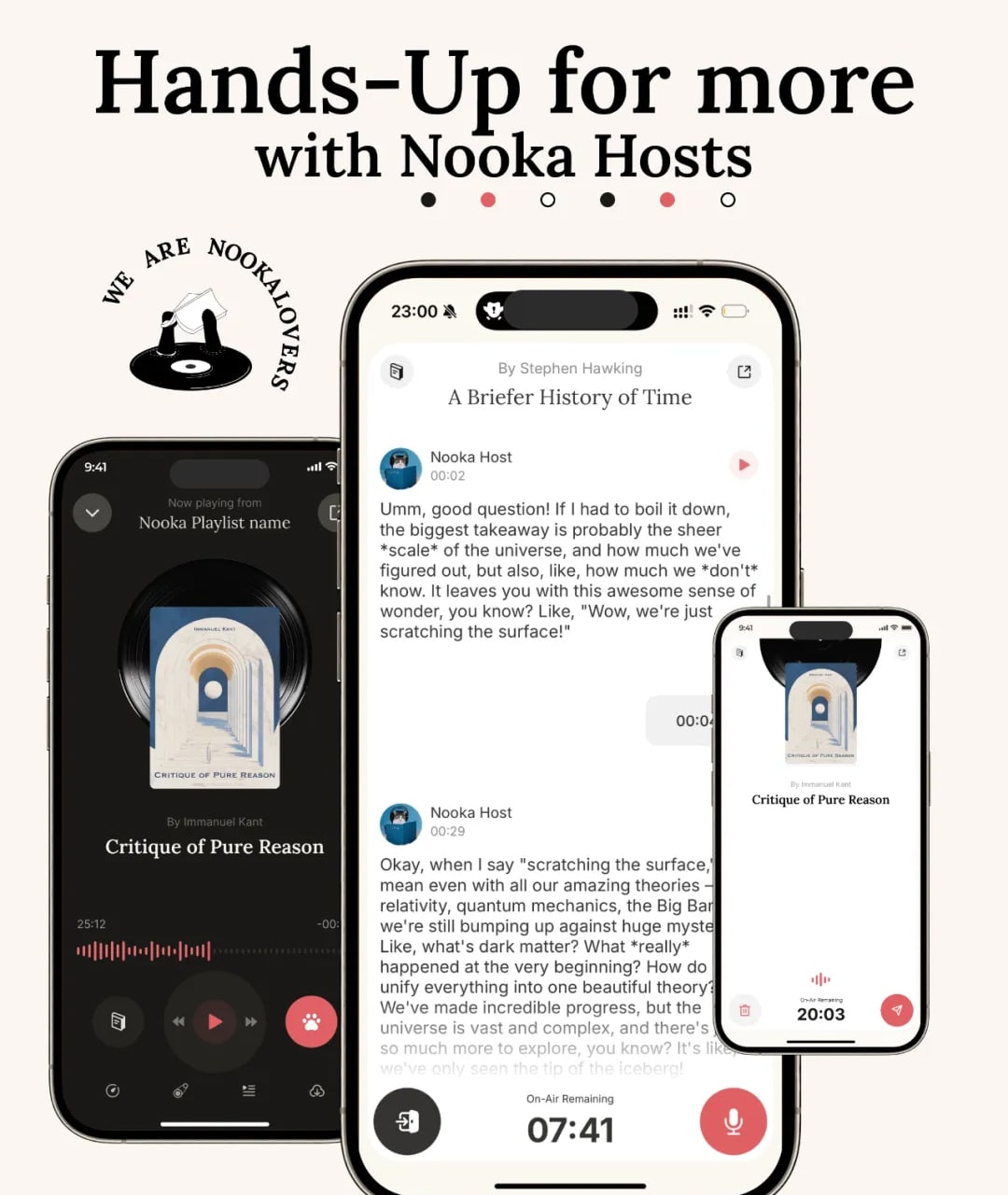

Header image source: Nooka.

100 AI Creators is a weekly series featuring conversations with China’s leading minds in artificial intelligence. As technology evolves, their perspectives shed light on the ideas driving the AI era across borders.

99.9% of people will never read Immanuel Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason.” But Tang Kaixin still wants to give it a shot.

Now, a new app called Nooka has emerged. In just 20 minutes, it can drop you straight into Kant’s universe, one where “the subject’s experience constructs the objective world.” Nooka doesn’t summarize or skim through the 800-page tome. Instead, it uses artificial intelligence to reimagine it as a trendy podcast.

Imagine a host styled after Joe Rogan, a popular talk show personality in the US, explaining Kant’s transcendental dialectic with The Matrix as a metaphor. Another voice chimes in with a rebuttal:

“So… are you saying Kant was the first true believer in the metaverse?”

And if you pose a question, the AI jumps in. Under the Elon Musk episode, one listener asked whether Musk and a prominent Eastern figure shared similar leadership styles. The AI picked up the thread with ease, finding deep connections where most people wouldn’t, and the user, ostensibly feeling inspired, kept the conversation going.

A few exchanges later, a new episode emerged: Musk and Stalin: Mirroring Tech Utopias and Mass Mobilization. If your chat with the AI gets interesting enough, Nooka might even feature it on the app’s homepage.

Born in 1995, Tang is building a new kind of content platform powered by AI. He believes each generation of media redefines who gets to be a creator.

Kuaishou turned county youth into live streamers. Douyin found hidden actors. Bilibili championed obsessive video editors.

Now, Tang is reinventing what it means to be a “questioner.”

On Nooka, you don’t need a script, or editing chops, or even a well-thought-out story arc. All you need is a compelling question, and the AI will run with it.

That’s the genesis of an episode. In this world, creators are no longer born from technical skills, but from curiosity. Tang believes that building a next-gen content platform isn’t about expanding the creator toolkit. It’s about redefining where creation begins.

Tang doesn’t fit the typical profile of a tech founder.

He has worked at ByteDance and Kuaishou, two of China’s fiercest AI battlegrounds, and even joined the early founding teams of several large model startups. But he doesn’t carry the usual traits of a growth hacker or platform-obsessed product person.

His first job out of college was at Kuaishou. When he joined in 2017, the company had fewer than 1,000 employees but was already nearing 100 million daily active users. The engineering culture ran deep. Many of his colleagues had backgrounds from Tsinghua, Peking University, or other elite research institutions. Yet the audience they served came from an entirely different expressive universe:

“In the office, you saw these Silicon Valley-style engineers with elite system architecture skills. But the most explosive content in the algorithm’s feed came from small towns, construction sites, and rural villages.”

Like many of his peers, Tang admits he didn’t understand that world at first. It was the algorithm that decoded their language and made their voices the most widely heard.

At ByteDance, he led a project that broke from the usual mold: the digitization of ancient Chinese texts. It all started with a simple reason: the founder liked reading them. But many classics were only accessible through overseas archives, with longstanding gaps in China’s own public digital resources. Tang took it upon himself to systematize and publish the material, making 20,000 classical works freely available online.

“This project didn’t make money for ByteDance, and no one saw it as strategically important,” he said. But Tang said he followed through anyway, completing something he saw as “unnecessary, but worthwhile.”

Tang studied architecture at Tongji University and once spent over half a year working with a non-governmental organization in one of China’s least-developed rural regions. In the Xiangxi mountains, there were no blueprints or automated planning tools. Feedback came slowly: three months to build a house, six to bury a water pipe.

These scattered experiences left a deep impression. They convinced him that in spaces untouched by data or algorithms, there are still things worth building.

In a sea of eccentric, hoodie-clad AI natives, Tang comes across as the clean-cut overachiever in a button-down shirt and trench coat. He doesn’t wear his ambition on his sleeve. He’s not chasing the next big trend.

Instead, he operates by a quiet principle: understand the full extent of both technical and personal limits, then make the best decision possible and go all in.

The following transcript has been edited and consolidated for brevity and clarity.

“Carving a boat to find a sword”

AI Now! (AN): Nooka is your first startup. Why a content platform? And why focus on audio instead of text or video?

Tang Kaixin (TK): I started thinking seriously about this in late 2024 and officially launched in February. Two shifts caught my attention.

First, the leap in TTS (text-to-speech) tech. For the first time, state-of-the-art models could produce voices that were genuinely listenable, not robotic or uncanny. In other words, AI-generated audio became actually consumable.

Second, the growing sophistication of large language models (LLMs). With more affordable access to thinking-level models like Gemini 2.0, LLMs can now engage in thoughtful, idea-rich discourse. They can pull in external references rather than just output shallow summaries.

Combine those two, and I realized: audio was ready. It wasn’t just that AI could make content, but that it could now make high-quality, listenable content.

AN: That’s an interesting angle. Most founders start by asking what they want to create, whereas you started by defining what the models can actually do.

TK: Because I’ve learned that lesson the hard way.

Before launching Nooka, I was at SenseTime, leading a team building a consumer-facing AI product. We were trying to create a design agent that resembles what Lovart is doing now. But even state-of-the-art models like Claude 3.5 couldn’t deliver usable output at the time. We bet that our in-house model would catch up, but the progress kept stalling.

To meet deadlines, we had to patch over model flaws with product hacks. But that’s just carving a boat to find a sword. The moment a better model comes out, whether that’s Claude 3.7 or Gemini 2.5 Pro, all your patches become obsolete. The only elegant approach is one that co-evolves with model capabilities.

You see this clearly with Devin and Cursor. Devin raised more money early on and aimed to be a fully autonomous AI programming assistant from day one. But it overshot model capacity, so completion rates tanked. Cursor played it smarter by focusing only on what models could actually handle well. When the models improved, it didn’t just stack new features. It rethought what new experiences those models could support. That’s why Cursor has pulled ahead while others still struggle.

The key is: don’t build products in defiance of model limits. It’s the surest way to fail. You need a system that evolves alongside model development.

AN: So why use books as your content form? There are many ways to do audio.

TK: More accurately, we reconstruct books, not summarize them.

On the production side, our AI agents are already capable of generating high-quality audio. What matters more is the quality of the source material we produce them from.

Books, especially timeless classics, offer more enduring informational and intellectual value than news or hot topics. They come with built-in structure, dense information, and cultural capital. And when we rework them using AI, we can often sidestep most copyright concerns.

At the end of the day, books offer a strong foundation for content quality. We’ve trained the model to the point where it can riff for eight minutes on just a single word, full of punchlines and callbacks. But that kind of output doesn’t actually hold much value for listeners.If we want a real content loop, quality has to start at the source.

AN: But why not just read the book?

TK: I think deep reading and format innovation can coexist. A 20-minute audio version of Kant will never replace the full 800 pages. But most people will never read “Critique of Pure Reason” anyway.

Modern attention spans have been rewired by short videos and bite-sized content. That’s a structural shift. If knowledge compression is here to stay, then a 20-minute version that brings Kant to more people—well, that’s a win too.

Bring books to life, not summarize them

AN: You don’t sound pessimistic about these trends. About Nooka’s book reconstructions, what do they actually look like?

TK: It means bringing knowledge to life, not just compressing or narrating.

Take Kant’s theory of transcendental idealism. If you throw the original jargon at someone, 99% of listeners will tune out instantly. But if you say: “Imagine wearing a virtual reality headset you can never take off. Everything you perceive as reality is actually rendered by your brain.” Suddenly, the idea clicks.

That’s what we’re aiming for. A user hears that and thinks, “Wait, that sounds like The Matrix.” And they’re right, because that’s the modern cultural shorthand for what Kant proposed 200 years ago.

That’s what our English version does. For Japanese users, we might swap in Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell as the reference point. It’s all about making it click within different cultural frames.

AN: How did you train the model to interpret like that? Most AI models would probably compare Kant to Descartes or Schopenhauer, not The Matrix.

TK: That’s where character-based scripting comes in. I’ve listened to a lot of AI-generated podcasts. You can usually tell they are scripted. The topic is introduced, followed by a question, then a counterpoint, and so on. It’s formulaic. It’s formulaic.

What we do is create hosts with distinct personas. One is like Lex Fridman, thoughtful and analytical. The other is more like Joe Rogan, a punchline-loving, open-ended talker.

AN: So it doesn’t feel like AI forcing weird analogies. It feels like two hosts talking within their personalities and worldview.

TK: Exactly. We trained the models on their voices and styles, and fine-tuned the behavior. They have now “covered” over 1,000 books, and we’re pushing toward 10,000. We’re currently rejigging the content.

AN: Going from 1,000 to 10,000 sounds ambitious. How do you choose what books to do?

TK: We started with 1,000 books to gather feedback and fine-tune generation quality. The selection includes bestsellers like “Steve Jobs,” “Elon Musk,” and “The Nvidia Way,” alongside foundational works like “Critique of Pure Reason.” People assume no one reads Kant’s books, but they still consistently show up on top sales charts.

AN: Why use “Critique of Pure Reason” to go viral on Xiaohongshu. Why not try using Musk’s bio to draw in users?

TK: That was purely personal preference. One of our team members has a PhD in philosophy. She studied computer science as an undergrad, then went on to do her doctorate in AI and philosophy at Tsinghua.

With consumer products, your values and aesthetics inevitably bleed through. For me, Critique of Pure Reason is one of the most influential books I’ve ever encountered—even if I’ve never finished it cover to cover.

Internet-era product managers won’t survive the AI era

AN: Before Nooka, you moved between big tech firms, startups, and leading AI companies. Why leave ByteDance? At 28, you were already running a division.

TK: It’s true that I climbed pretty quickly during those years, but retiring at ByteDance was never the plan. In 2023, I was already working on AI-related products, and I could feel firsthand how fast the LLM wave was progressing.

That shift was exciting for me. I wanted to get closer to the technical core. So after leaving ByteDance, I joined 01.AI.

AN: Isn’t ByteDance already close to the tech?

TK: Only once I joined a model lab did I really understand the difference between working with AI and actually building it.

At ByteDance, our workflow was straightforward. As product managers, we defined problems, like whether a certain feature can lift retention by 1%. Then a roadmap is laid out for engineers to implement. I thought I understood the tech. I’d studied computer science, could write some code. But in reality, I was still working with an internet-era mindset. Technology was treated as a black box. We focused on inputs and outputs, not the complexity inside.

Model companies are different. Model behavior is unpredictable and evolves fast. Even building a simple chat feature depends on whether you’re using GPT-4o, Claude 3.7, or Gemini. Prompting strategy, fallback logic, error handling—every decision shifts the experience.

You can’t figure that out in a few meetings. You need to build benchmarks, run experiments, and feel each model’s quirks. Now I might spend an entire day fine-tuning temperature settings. You can’t learn that from reading papers.

AN: So what happens to product managers in the AI era?

TK: I think the role will change completely. You can’t just be someone who identifies user needs. You need to understand how models behave, and how they’ll likely evolve. At the same time, you still have to think like a product designer and analyze what kind of experience this tech enables, and how users might interact with it.

In the AI era, this all-rounder perspective is essential. The old, siloed product manager role won’t survive. You simply can’t build relevant products without understanding the tech. If you try, something will break.

At Nooka, I write a lot of the code myself. I spend probably half my time programming.

AN: Let’s go back to the origin of Nooka. You chose book reconstruction because of the twin leaps in TTS and LLMs. But in this system, what role is left for humans?

TK: It’s true. AI can already handle a large portion of content creation: structure, tone, pacing, even the rhythm of a conversation. But there are two things it can’t do: determine what’s “good,” and generate the seed, or the initial idea that kicks things off.

By design, large models output the most statistically likely sequences of tokens. They are inductive engines, not creative ones. Without external input, they can’t decide whether to pursue a strange angle or explore an unusual leap. But once you feed in a novel idea, they are great at developing it, sometimes even building it out into something surprisingly coherent.

So what we’re really doing isn’t letting AI do the creating. We’re building a system that continuously surfaces people’s tiny questions and curiosities, and letting AI unfold them into something bigger.

AN: In other words, you want to activate a new kind of creator through the system itself.

TK: Exactly. In this structure, you don’t need to write a script, record audio, or host a show. If you can offer one interesting angle, that’s enough to become the starting point for an episode. Creation happens in the act of consumption. Just by listening, you’re already shaping what comes next.

AN: There are some brilliant comments on Bilibili too. How is your approach different?

TK: Bilibili does have great comments, but they don’t feed back into anything. They stay at the level of expression. They don’t become productive inputs, so they don’t form a closed loop of creation.

The same goes for Douyin. You’ll find thousands of insightful comments under a video, but none of them are organized, surfaced, or reused. So is it content creation? Sometimes yes, but not in a way that can power a platform.

What we’re trying to do is see if those light expressions—a sentence, a stray thought—can be caught by AI, expanded, and turned into new, consumable units of content. If that works, the viewer becomes the creative spark.

It’s not just making creation easier. It’s a different starting point. AI becomes the tool that catches those fleeting sparks of thought and builds them into something that could inspire others.

AN: So you believe that just triggering a spark can unlock a new kind of creative productivity?

TK: Kuaishou and Douyin both started as tools. Eventually, they became massive content and social platforms. I believe whoever redefines what a creator is, defines the next generation of content platforms.

Quick takes

AN: What’s shocked you most in AI since 2025 began?

TK: The fact that AI agents have actually become viable.

It’s not just that the product format finally works, it’s reshaping how we build teams. At Nooka, we’re testing whether a team of 5–10 people plus 100 agents can outperform a setup of 50–100 humans.

We now run editing agents, synthesis agents, and tons of small AI tools. Think of them as freelance contractors. If they are cost-effective, they stay.

AN: What did you misjudge in AI last year?

TK: I underestimated general-purpose agents like MindOS and ChatDev.

I thought anything with less than 90% task success was useless. But users proved more tolerant. For slide decks or web builders, even 50–60% success is fine. People learn to work around the flaws.

So I’ve moved from thinking it needs to succeed broadly to recognizing that doing just one thing well might be enough for it to endure.

AN: What are you most looking forward to in 2025?

TK: My wedding!

Also, I’m excited about self-improving AI systems. Projects like Sakana AI’s Darwin Godel machine or DeepMind’s AlphaEvolve suggest that models may soon evolve themselves without needing pretraining data.

It’s fascinating, and a little terrifying. Like the start of a sci-fi apocalypse novel.

AN: Lastly, recommend three books you love.

TK: First would be Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason.” I haven’t finished it yet, but I’ve been reading it for years. Every time I return to it, I understand something differently.

The other two would be “Steve Jobs” and “Zhuangzi.”

100 AI Creators is a collaborative project between AI Now! and KrASIA, highlighting trailblazers in AI. Know an AI talent we should feature? Reach out to us.