On March 29, a Xiaomi SU7 barreled into a concrete divider in Tongling, Anhui. The impact ignited the car, reducing it to a charred shell. All three people onboard were killed.

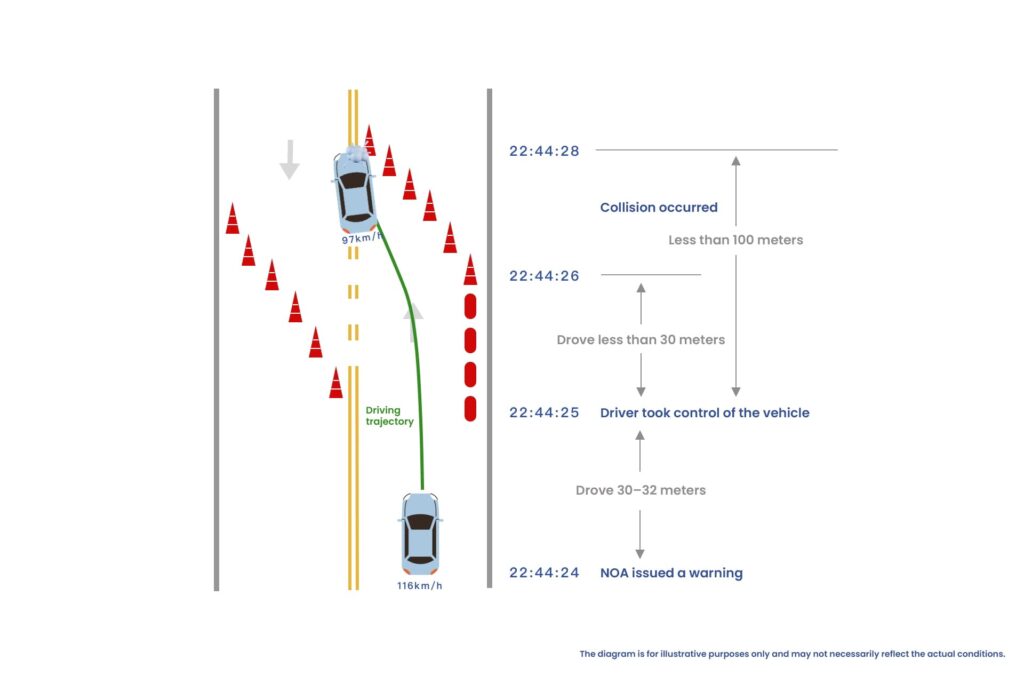

Two days later, Xiaomi confirmed the incident and released partial driving data from the vehicle. According to the logs, the SU7 had been traveling at 116 kilometers per hour with its navigate-on-autopilot (NOA) feature engaged. The system, meant to assist with highway driving by automatically managing speed, lane changes, and ramp navigation, issued a warning about an obstacle ahead. Within a second, the driver took over. But just three seconds later, the crash occurred. The car was still moving at 97 km/h when it hit the barrier.

Xiaomi said the accident took place in a roadwork zone, where traffic had been diverted into an oncoming lane. A day after the crash, the company formed a task force to assist with police investigations. Authorities in Tongling have also opened an inquiry.

The car involved, Xiaomi’s SU7, is the company’s first serious foray into the automotive space—and a hit. Nearly 186,000 units were sold in its first year, and the backlog is so long that wait times now stretch up to a year. Much of that demand is driven by brand trust and the personal appeal of Xiaomi founder Lei Jun, who has reinvented himself as an automotive industry personality.

Lei has claimed that nearly 30% of SU7 customers placed their orders without even seeing the car in person. For him, that’s proof that consumers believe in the brand—and in him.

But the Tongling crash has cast a shadow over the trust Xiaomi has worked so hard to build.

Smart driving has become a defining theme in the auto industry’s evolution. BYD, the sector’s dominant player, has been aggressively promoting its own systems—spurring rivals like Geely and Chery to keep pace. As a result, highway navigation assist features are now showing up in vehicles priced below RMB 100,000 (USD 14,000), making advanced driving tech accessible to a wide slice of the market.

Automakers like Li Auto, Xpeng, Nio, and brands under the Harmony Intelligent Mobility Alliance (HIMA) have also staked their identities on smart driving. This year alone, nearly 10 million cars in China are expected to ship with highway-level navigation—a figure that would represent almost half of all new passenger vehicles sold nationwide.

Against this backdrop, the fatal SU7 crash has hit a nerve. Xiaomi’s high profile, combined with the breakneck expansion of smart driving tech, has reignited public concern about just how safe these systems really are.

A critical two seconds

Driving logs released by Xiaomi show that the SU7 was traveling at 116 km/h with its navigate-on-autopilot (NOA) system engaged at the time of the crash.

Prior to the incident, the system had issued a series of minor driver alerts, including a warning about hands-off driving—triggered when it detected the driver’s hands were not on the wheel. These alerts only clear once the wheel is firmly gripped again.

After eight minutes of smooth travel, the system suddenly flagged an obstacle ahead and began to decelerate. From that alert to the moment of impact, just two seconds passed.

In that brief window, the driver took control. The vehicle was still moving above 100 km/h. The driver steered 22 degrees left and applied the brakes at only 31% pressure—well below the 60% typically needed for hard braking. The combination of an aggressive turn and soft braking made it difficult to reduce speed or maintain control, increasing the likelihood of hitting roadside structures.

An automotive R&D engineer told 36Kr that at 116 km/h, a 22-degree steering input causes a major shift in wheel direction. Since the SU7’s standard model uses rear-wheel drive, such a maneuver at high speed could easily trigger a skid. “Making a sudden steering move at high speed is extremely dangerous,” the engineer said.

Photos from the crash show that the vehicle struck the concrete barrier on its front passenger side.

According to another expert, the divider had been placed along the median between two lanes. As the driver attempted to veer left, the car failed to fully clear the obstacle, resulting in a front-right collision. “This is a classic offset collision,” the expert said—one that’s commonly used in industry crash tests.

In September 2024, the China Insurance Automotive Safety Index (C-IASI) crash-tested the SU7 under similar conditions, simulating a 25% passenger-side offset impact at 64 km/h. The car received the highest safety rating, and the crash test dummies were unharmed.

But the Tongling crash happened at far greater speed. “The car was still going 97 km/h when it hit,” the expert added. “No vehicle is built to withstand that.”

The impact sparked a fire that engulfed the car. Images from the scene show it burned down to its frame.

Despite Xiaomi’s efforts to go beyond industry norms in battery safety, even LFP (lithium iron phosphate) cells—which are more stable than other chemistries—have limits. A battery industry source told 36Kr that Xiaomi uses aerogel insulation to contain thermal spread. Still, at nearly 100 km/h, a collision can crush battery cells and rupture the electrolyte layer.

“LFP batteries generally don’t ignite under minor impact—they might smoke, but fires are rare,” the source said. “But once the cells are torn open, ignition is almost guaranteed.”

“Most battery packs are designed with thermal protection for crashes up to 80 km/h,” the source added. “Designing for higher-speed collisions would require far stronger structures up front, and most automakers won’t take on that cost for what they see as edge cases.”

Ultimately, the root cause appears to be a dual failure—both the smart driving system and the human driver failed to detect and react to the obstacle in time.

Smart driving’s rise—and its safety blind spots

Smart driving engineers interviewed by 36Kr said the conditions surrounding the SU7 crash expose a scenario that’s difficult for the entire industry—common in the real world, but still technically complex to handle.

The standard edition of the SU7 is built with an entry-level smart driving stack. On the hardware side, it uses a single Nvidia Orin N chip capable of 84 TOPS of compute, one millimeter-wave radar, 11 cameras, and 12 ultrasonic sensors. There is no LiDAR. Xiaomi’s in-house software provides features like highway navigation assistance.

According to an industry insider, the system is based on two widely adopted techniques: bird’s eye view (BEV) perception and occupancy networks (OCC)—approaches popularized by Tesla and now used by many EV makers.

BEV-based systems can detect objects up to about 100 meters away on a highway, but detection reliability drops significantly beyond 60 meters. “At 100 km/h, that gives the system roughly 3.6 seconds to react,” the insider said.

“Long-range detection of static obstacles is a known weak spot,” the person added. “LiDAR would help—it’s better at picking up objects early.”

Another engineer pointed out that poor visibility or unclear road layouts make it even harder. “In real-world driving conditions, slowing from 100 km/h to zero isn’t always technically feasible. Reducing speed to 60 km/h is much more realistic.”

In the SU7 crash, Xiaomi’s logs show that the system issued its obstacle alert just two seconds before impact. The barrier could have been a concrete divider, cones, or water-filled barricades at the construction site. Based on the vehicle’s speed, it may have been 60–130 meters away when the system registered the obstacle.

At that distance, another safety layer should have been activated: automatic emergency braking (AEB).

“AEB should be able to cut speed to 30 or 40 km/h if it detects something within 100 meters,” one expert said. But with the car still traveling at 97 km/h at impact, it appears AEB didn’t engage.

Xiaomi had previously claimed that its AEB could detect stationary vehicles and stop safely from speeds up to 135 km/h. But industry insiders told 36Kr that AEB remains far from foolproof. Many systems, especially vision-based ones, struggle to identify irregular or low-profile obstacles like cones, water barriers, or debris.

A review of Xiaomi’s user manual reinforces that point. Under its collision warning system limitations, the company lists several objects that may not be detected—fallen rocks, prone pedestrians, animals, and construction materials among them.

“That’s a legal disclaimer, essentially,” one engineer said. “But out on the road, most drivers don’t recall which scenarios the system might fail in.”

Complaints about AEB not reacting to stationary objects—especially at construction sites—aren’t unusual. Even high-end vehicles with top-tier smart driving stacks receive frequent support tickets related to low-speed collisions with temporary road features.

So while companies continue to market smart driving systems using phrases like “end-to-end” and “large model architecture,” the technology is still grappling with basic detection challenges. Real-world edge cases remain a hurdle—and those gaps are starting to show.

The race to democratize smart driving may be outpacing safety

In 2025, smart driving is being sold as a mainstream feature. Automakers are aggressively marketing it as something for everyone—even as much of the underlying software is still in development. With technical parity still elusive, the hardware race has become the next best way to capture early mindshare.

For many consumers, smart driving has come to represent not just convenience, but status—an emblem of tech-savviness and modern living. Those who opt out may be seen as behind the curve.

That perception came into sharp focus in the case of the SU7 crash. According to Qingdao-based outlet Zhengzai News, the young woman behind the wheel had often assured her mother that the car’s smart driving system was “convenient and safe.” Her mother, wary of overreliance on automation, had urged caution. “I told her she would regret it one day,” she recalled. “She told me the technology was proven.”

But the reality is more complicated. Even engineers who work on these systems say they avoid using them at night, aware of their blind spots. For everyday drivers, it’s even harder to assess which systems are reliable, what chipsets matter, and where the risks lie.

One engineer told 36Kr that a leading automaker faced over 100 smart parking demo failures in its showrooms—hurting sales. The company is now reportedly handling more than 20,000 support tickets tied to smart driving glitches.

There’s no doubt the technology can offer real benefits: reduced fatigue, sharper environmental awareness, and faster reaction times. But overmarketing these features—or rushing to outdo competitors—can backfire. When expectations outpace performance, safety risks and product quality issues aren’t far behind.

Automakers have a responsibility to clearly communicate what their systems can—and cannot—do. Being called an “industry leader” or having a “tier-one stack” doesn’t change the fundamentals if the tech can’t hold up in real-world conditions.

For Xiaomi and others, a surge in orders may reflect consumer trust. But in an industry under the spotlight, public attention cuts both ways. Staying grounded, setting realistic expectations, and pacing product development accordingly may be the only way forward in a market where buzz alone won’t keep you ahead.

KrASIA Connection features translated and adapted content that was originally published by 36Kr. This article was written by Xu Caiyu for 36Kr.