On July 25, a torrential downpour swept through Beijing just as Taiwanese rock band Mayday took the stage for their first concert in the capital. The skies opened, drenching fans and performers alike. Lead vocalist Ashin, unfazed, joked that their bond with the audience was a kind of “twisted fate.”

“Snagging a ticket? Exhausting. Traffic? Even worse. And on top of it all, you get dumped on by this huge storm the moment the show starts,” he said. “Tired yet? That rain hit you, but it hit me straight in the heart.”

For longtime fan Baiying (pseudonym), the weather barely registered. The concert joy had started long before the first note. A month or two ago, Beijing had already turned into a “Mayday pain city,” she said, referring to the city’s transformation into a shrine for avid fans.

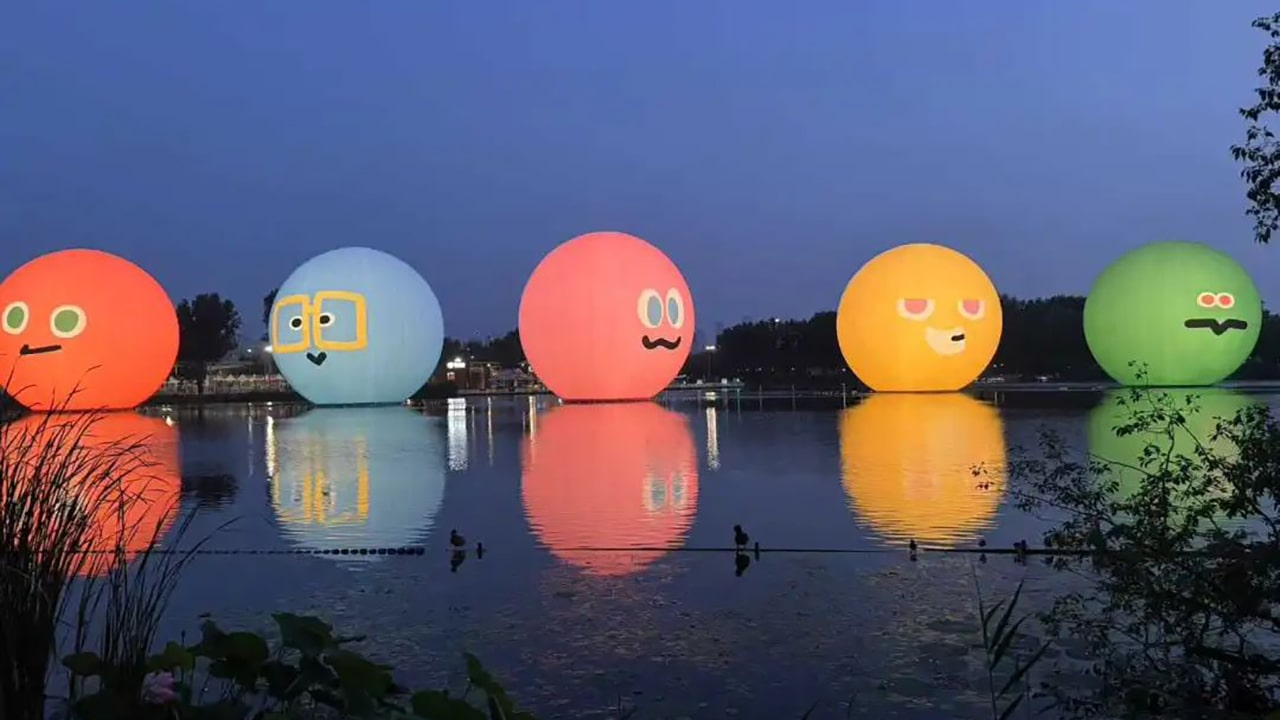

Around Chaoyang Park, public installations resembling five spheres, likely a nod to the band’s five members, lined the grounds. Along the Liangma River, fans built paths and bridges inscribed with lyrics. At a pop-up exhibition in the Xidan commercial district, stores displayed signs that read “WMLs welcome,” using a fan-created acronym for Mayday fans. On the subway and in the streets, plush carrots—a reference to a band character—dangled from bags, signaling quiet membership in a shared subculture.

“It’s strangers bringing strangers a very specific kind of happiness,” Bai said.

Scalper Yongjia (pseudonym) found happiness of a different sort. Mayday tickets sold easily, achieving a rare success in a year when many big-name concerts underperformed. High-priced tickets for Jay Chou, Wang Leehom, David Tao, and JJ Lin no longer guaranteed profits. Instead, niche and older acts surged in popularity.

The concert economy, like its audience, was shifting.

No longer confined to teenagers and young adults, the scene now includes middle-aged professionals, retirees, and parents. Outside venues, parents wait for their children to exit. Inside, seniors wave glow sticks and sing along.

Tony (pseudonym), a veteran concertgoer, has watched this evolution. “Before the pandemic, I’d already seen all my favorite artists live,” he said. “When lockdowns ended in 2023, I thought concerts were over. No one was organizing them anymore.”

He rushed to see Rene Liu in Hangzhou, believing it might be his last chance. He didn’t expect the tour to last three years, or for ticket prices to surge beyond his limit. That’s when he realized: the concert boom was just beginning.

During the same period, ticketing platform Damai entered its golden age. Its revenues rose from RMB 228 million (USD 31.9 million) in 2023 to RMB 2.06 billion (USD 288.4 million) by 2025. Fans began to voice frustration at the platform’s dominance. At concerts, artists thanking Damai would be met with crowds chanting for it to go bankrupt.

Yet the demand persisted. People exchanged hundreds or thousands of RMB for a few fleeting hours of music and euphoria, before returning to daily life as parents, employees, or students.

Few experiences in China offer such total detachment from social roles.

A century ago, Austrian author Stefan Zweig wrote “Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman,” in which a reserved aristocrat abandons decorum for a brief embrace of passion. For many today, a concert provides a similarly radical escape.

A spreadsheet for joy

Tanhuo (pseudonym) works at a major tech firm. After becoming a devoted fan of singer and actor Tan Jianci, she began posting concert photos and video edits on WeChat. Friends thought she’d switched careers to join the entertainment industry.

“I told them I just really liked him,” she said. “They were shocked as I never seemed interested in pop culture before.”

But everything changed. She has logged into Tan’s fan forum for 653 consecutive days. She bought a RMB 10,000 (USD 1,400) “Samsung concert gear” phone to capture better videos. Her most expensive concert ticket: RMB 20,000 (USD 2,800), from a scalper.

She tracks all her transactions in a spreadsheet, budgeting RMB 20,000–30,000 (USD 2,800–4,200) per show to hire multiple agents. Each booking can cost RMB 3,000–5,000.

Even with that preparation, she missed the artist’s debut concert. None of her agents secured a ticket. She eventually paid RMB 9,800 (USD 1,400) on the secondary market.

“These deals aren’t protected by law,” she said. “But I calculate the risk. I can afford to lose a few thousand RMB, but I can’t afford to miss the show.”

Many in China still see concerts as a luxury. In 2024, the average per capita disposable income was RMB 40,000 (USD 5,600), with only RMB 3,189 (USD 446.5) allocated annually for education, culture, and entertainment. Even the cheapest seats for Jay Chou or JJ Lin can cost RMB 400 (USD 56).

Getting a ticket without paying extra? That’s harder than winning the lottery.

Many turn to scalpers, but that route depends on knowledge and connections. Not all scalpers are equal. Their “level” in the supply chain determines the price and reliability.

“Scalpers make money based on where they sit in the chain,” Yongjia explained. A ticket bought for RMB 2,000 (USD 280) by a top-tier scalper might sell for RMB 4,700 (USD 658) after passing through several hands.

Yongjia finds half his clients through Douyin and Xiaohongshu live streams to prove he’s legitimate. The rest come via referrals and private groups.

“High-net-worth clients bring others like them,” he said. “If someone drives a Maserati, they are not giving a referral for someone with a rusted hatchback.”

Tanhuo doesn’t drive a Maserati. For her, those three hours are a reward for her work and efforts. “That joy makes everything else worth it,” she said.

Still, the shows pass quickly. “My face aches from smiling,” she said. “And after it ends, it’s like a blackout. I try to hold on to every memory.”

Living as oneself for three hours

Tanhuo laughs at most concerts. She has cried only once, when Tan handed the mic to a 70-year-old woman who shouted, “I’ll always love you, Tan Jianci!”

“That word is something I’ve never said out loud,” Tan said. “She reminded me of my grandmother.”

Getting older fans through the ticket gauntlet is no small feat.

Nicole (pseudonym) got her parents into a Phoenix Legend concert. Her mother, a longtime fan, had never seen them live.

“They tried to stand and dance but eventually sat down,” Nicole said. “Still, they waved glow sticks and recorded everything.”

On the way home, her mother couldn’t stop talking. Nicole learned for the first time that her mother had once dreamed of becoming a singer.

“She used to clean while singing Han Baoyi. She was so young back then, just like me now.”

For Nicole, it was a reminder: “I need to take them out more. She said afterward, ‘I feel ten years younger.’”

Yifan (pseudonym) bought her father a ticket to see Andy Lau for RMB 680 (USD 95.2), not because she couldn’t afford more, but because he’d feel guilty if she did.

After the show, he proudly showed her videos. Outside the venue, men his age sang Lau’s hits before the show even began. “That’s our generation,” he told her.

Yifan hopes her parents, by experiencing their own joy, will better understand her pursuit of independence.

At concerts, Tanhuo sees fans of all ages. “Some parents wait outside while their kids go in,” she said. “Other times, it’s the kids cheering while their parents sing along.”

On Xiaohongshu, she sees teens swapping concert tips. “When I was their age, I was just happy to buy fried chicken,” she said. “They are already living fully.”

Intergenerational support is increasingly essential, and increasingly common.

Scalper Yongjia saw the trend first. His bestselling act last year wasn’t a young idol but Andy Lau.

Tickets weren’t heavily marked up initially. Yongjia paid RMB 5,000 (USD 700) for seats with a face value of RMB 2,000 (USD 280), then sold them for RMB 6,000–7,000 (USD 840–980). The returns were strong.

“Andy Lau fans are over 40. They’ve got spending power,” he said. A woman over 60 insisted on a seat in the front row, at the center. “I don’t want anyone blocking my view,” she told him.

iiMedia Research found that most Chinese consumers budget RMB 1,001–3,000 (USD 140–420) per concert. Among those aged 36–45, about 30% are willing to spend RMB 3,001–5,000 (USD 420–700). This one-child-policy generation was the first to grow up immersed in pop culture.

Three golden hours, fourfold returns

Last year, Baiying (pseudonym) attended 15 concerts: ten by Mayday, and five by JJ Lin. Her favorite wasn’t in a major city but in Taiyuan.

Taiyuan, a second-tier city in northern China, delivered far more than just a concert. Fireworks and drone shows lit up the sky. Each fan received a gift bag of local specialty treats at their seat. The rail system added fan-only train routes. For three days, concertgoers could ride any city bus or visit local attractions for free with their ticket.

“Everywhere you went, you’d run into other fans. There was so much to do, so much to talk about,” Baiying said.

Behind this spectacle was strong municipal support. Taiyuan’s local government embraced what’s become known as the concert economy. Cities like Xi’an, Hainan, Shenzhen, and Shanghai have followed suit, rolling out policies to attract major performances.

Why? Because concerts do more than fill arenas. They fill hotels, restaurants, shopping centers, and train cars. A single show becomes an engine for citywide spending.

The ripple effect extends far beyond music. In June, during China’s 618 shopping festival, singer Zhou Shen’s merchandise line sold out in a single second, racking up sales in the tens of millions of RMB. Last year during Singles’ Day, Mayday’s “Mojo Carrot” plush toy ranked third on Tmall’s bestseller list for stuffed toys, just behind Jellycat and Disney.

Ahead of Mayday’s Beijing performance, Baiying queued for 90 minutes on a weekday at StayReal’s pop-up store in Xidan just to snag merchandise. “I heard the weekend line takes four hours,” she said.

Merchants have learned to ride the wave. In the two weeks before the concert, every storefront in Xidan’s The New had a sign: “WMLs welcome.” Flash your ticket or show your plushie, and you’d get a discount. In Taiyuan, vendors printed Mayday characters onto old-school yogurt bottles to entice fans.

Every poster of celebrity Tan’s concert includes a “dress code hint,” a specific color theme fans use to coordinate outfits, fueling retail fashion sales. Tanhuo and her circle hunt down matching pieces for every show.

The electronics sector is tuned in too. Aside from the Samsung phone Tanhuo bought, Vivo, Oppo, and Xiaomi have each released models optimized for long-zoom, low-light concert recording.

And then there’s hospitality. Platforms like Trip.com and Klook now bundle concert tickets with flights and hotels. Outside stadium gates, Didi-labeled buses wait for fans headed home.

Taiyuan alone hosted 32 concerts in 2024, generating RMB 4.1 billion (USD 574 million) in consumption. Ticket sales made up just RMB 1.04 billion (USD 145.6 million), a quarter of the total. The rest came from everything else: the travel, food, shopping, and memories built around the event.

According to the China Association of Performing Arts, every RMB 1 (USD 0.14) spent on a ticket fuels an additional RMB 4.8 (USD 0.67) in related local spending.

Three golden hours onstage, and a whole economy is set in motion. Artists, managers, promoters, local governments, platforms, scalpers, food stalls, hotels—everyone gets a cut. Behind the scenes, it’s a story of timing, culture, and people.

The roots of today’s concert boom lie in the legacy of Mandopop’s golden era. And few artists represent that legacy more clearly than Stefanie Sun. In 2025, she returned to the stage after a decade-long hiatus. She had changed. Her fans had changed. So had the entire industry.

Yifan and Tony attended her Shanghai concert. Yifan cried during the crowd’s singalong. Tony, who’d brought tissues just in case, ended up smiling the whole time. For both, the concert stirred memories from the past decade, ones they hadn’t realized they’d been holding on to.

KrASIA Connection features translated and adapted content that was originally published by 36Kr. This article was written by Wang Yuchan for 36Kr.