Hundreds of venture capital firms from around the world are investing in India for the first time, suggesting a breakout moment for the country’s startups but also raising questions about whether the boom will be sustainable.

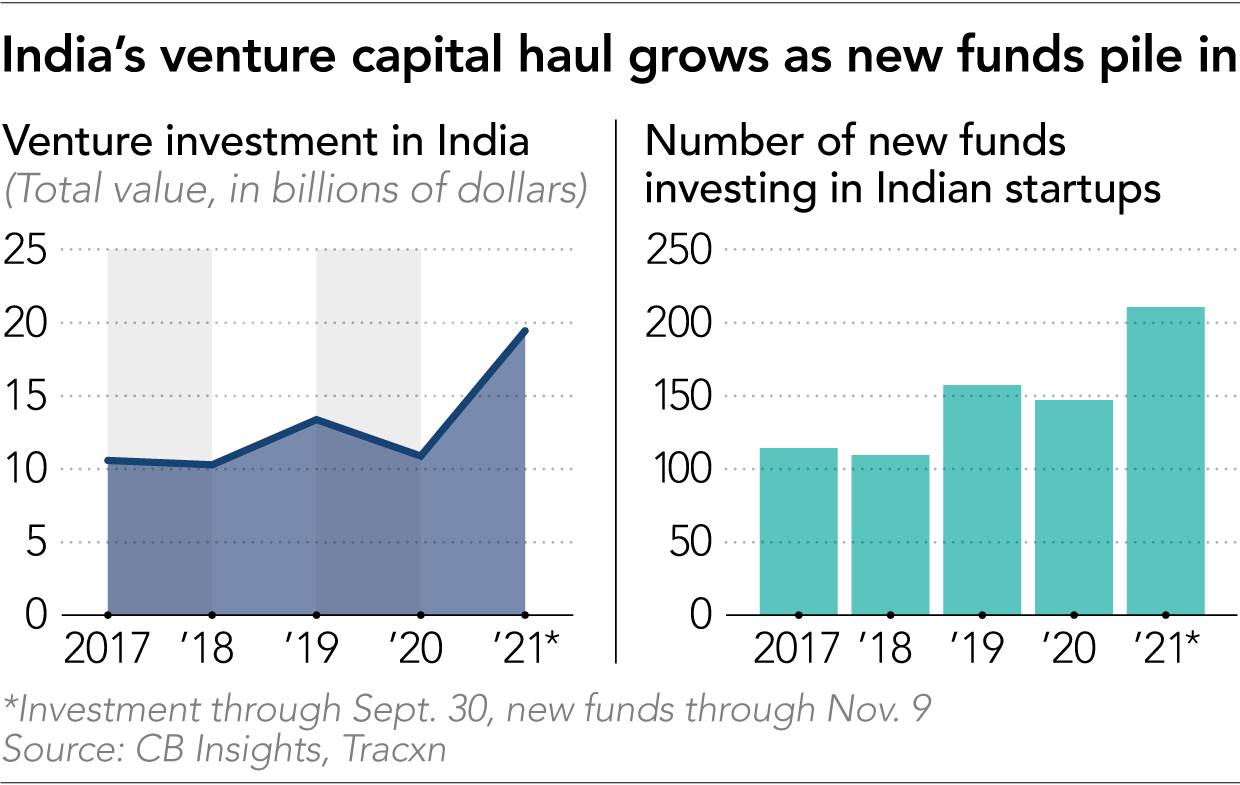

Some 211 funds made debut investments in India this year, about 64 more than the previous year, according to Tracxn, a startup data tracker.

Among the firms to have taken the plunge, after waiting in the wings through a decade of startup boom in India, are Andreessen Horowitz, TCV, Vitruvian Partners, and GSV Ventures. Kleiner Perkins, the Silicon Valley fund that quit India in 2014, is back in the fray.

In all, Tracxn identified 2,284 deals by 597 different VC funds so far this year.

Beijing’s regulatory crackdown on its tech sector has taken some of the sheen out of China’s appeal as the first-choice investment destination for global venture capital in Asia, while in India, buoyant public markets and the rapid adoption of online services in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, have added to the ebullience around Indian startups.

“There is a lot more liquidity sloshing around the ecosystem and some [has] of course been redirected from China to India,” said Armaan Kapoor, an investor at Singapore-headquartered venture capital firm January Capital. “But it will be a great disservice to India to just say that’s the primary reason for so many new funds coming in.”

January Capital first invested in India in October last year, taking part in the USD 2.5 million fundraising by education startup Kyt. Other recent debuts include Andreessen Horowitz backing the crypto startup CoinSwitch Kuber, Vitruvian Partners backing logistics startup Porter, and TCV investing in fantasy sports startup Dream11.

Venture capital inflow into India, home to 850 million internet users, was at an all-time high of USD 19.5 billion in the nine months to September, estimates CB Insights. The July-September quarter accounted for half the corpus, with USD 9.9 billion raised across 519 deals.

In comparison, venture investments in China in the July-September period were USD 25.5 billion, rebounding after two consecutive quarters of decline. Total venture investment in China in the nine months to September totaled USD 67.4 billion. Both India and China, however, pale beside the USD 210 billion invested in US startups in the nine months ended September.

“Investors in venture funds have received billions of dollars in payouts in the past couple of years following a series of bumper public listings in the US,” said Shivakumar Ramaswami, founder and director at Indigoedge, an investment bank. “In a low-interest market such as the US, they redeployed the capital in venture firms. Many of those had a China strategy and when China tightens the screw, markets like India benefit.”

Sensex, India’s benchmark index for public equities, is up 25% since the beginning of the year, on a par with the US Nasdaq thanks to investor excitement over tech stocks, while the Hong Kong Stock Exchange is down 8%.

A number of startups such as ride-hailing service Ola, logistics company Delhivery, hospitality startup Oyo, online pharmacy PharmEasy, and used car marketplace Droom are expected to list on Indian bourses through the first half of 2022.

The openness of the IPO market has addressed concerns over a lack of liquidity in India, as has a flurry of mergers and acquisitions activity, which promises another exit route for VC investments. M&A deals worth USD 90 billion were struck in the nine months to September, up 35% from the year ago period, according to research firm Refinitiv.

“In India, public listings are now a reality, unlike a few years ago, when it was a promise,” said Neeraj Shrimali, executive director, digital and technology, at Avendus Capital, an investment bank.

With a record number of investors buying in, lofty valuations are back. At least 35 Indian startups, all loss making, breached the USD 1 billion valuation mark this year, and several more are waiting on the fringes, just one funding round away from achieving unicorn status.

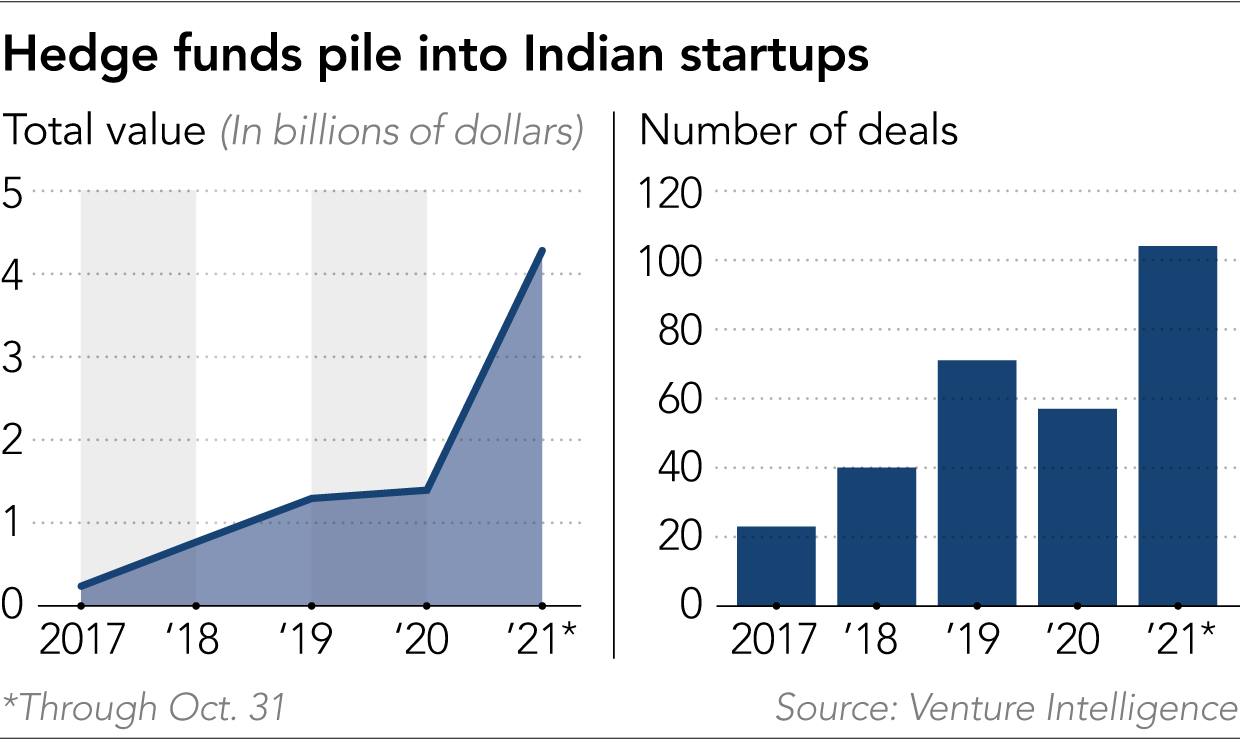

The exuberant valuations are also a function of some frantic deal making by hedge funds led by Tiger Global Management, which struck 46 deals, and Falcon Edge, which participated in 26. Hedge funds invested approximately USD 4.3 billion in Indian startups across 104 deals this year, almost three times the USD 1.4 billion invested in 2020, according to Venture Intelligence, a data firm.

The heady days are reminiscent of the funding boom in 2014 and 2015, when investors including Tiger and SoftBank poured billions of dollars in Indian startups at frothy valuations, enabling them to spend benevolently on customer acquisition. The euphoria turned into dismay in the following years when investors turned off the funding tap, baffled as companies piled up losses, with profitability nowhere in sight.

Much may hinge, therefore, on the financial performance of a new generation of startups, particularly those that have recently floated.

Shares of food delivery firm Zomato and beauty products retailer Nykaa continue to soar despite a weak performance in the July-September quarter. Zomato shares are trading at more than double the issue price of INR 76 (USD 1.02), despite losses swelling to INR 3.1 billion in that quarter, from INR 1.7 billion in the preceding three months. Its revenues during the period surged 22.6% to INR 14.2 billion from the quarter before.

But shares of the digital payments business Paytm, which completed the country’s largest initial public offering last week to raise INR 183 billion, at a valuation of INR 1.5 trillion, tanked 27% from their issue price of INR 2,150.

“It’s all about pricing it right,” said Rutvik Doshi, managing director at Inventus Capital India. “Just one underwhelming debut doesn’t change the India story. But, if the other tech stocks also plummet on Paytm’s cue and continue to remain low, it may impact the subsequent listings.”

Investors aren’t yet calling it a bubble akin to the rah-rah days six years ago, but they have questions.

“Are funds entering India because they have a long-term thesis, or they are sitting on extra dry powder and chasing some opportunistic return?” said Kapoor of January Capital. “If it’s more of the latter, then it’s definitely a problem.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.