Cryptocurrency entrepreneurs lured to Singapore by its apparent openness to the burgeoning industry are discovering just how difficult it is to legally operate in the city-state.

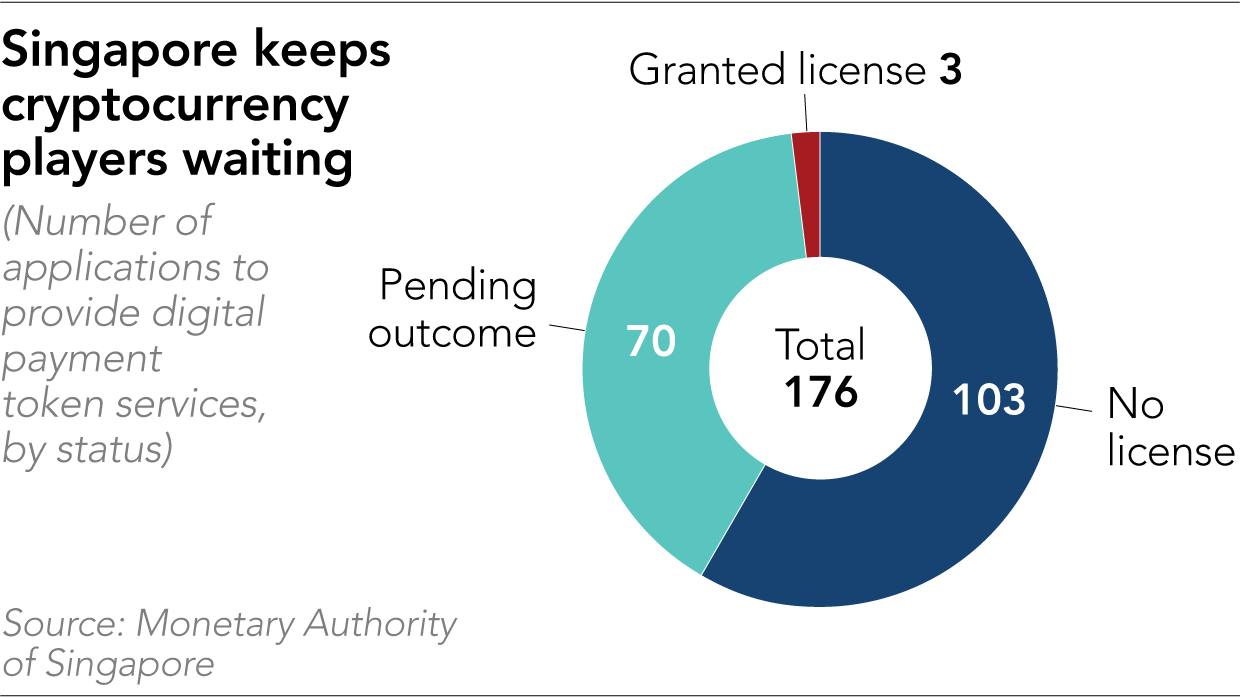

More than 100 of the around 170 businesses that applied for licenses to offer “digital payment token services” have now been turned down or withdrawn their applications, according to the latest figures from regulators.

And scores more face an uncertain future, operating under exemptions but amid a darkening mood over the approval process.

In early September, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) ordered Binance, one of the world’s largest crypto exchanges, to stop providing services to residents in the city-state, and last week Binance’s Singapore-only affiliate announced it also was shutting down its trading platform for the city-state. Dozens are confronting a similar fate.

Dubai-based crypto exchange Bitxmi is one of 103 companies that appear on the latest MAS list of entities whose exemptions allowing them to operate have been removed. Having set up in Singapore in late 2018, it was unsuccessful in securing a license, chief executive officer Sanjay Jain told Nikkei Asia.

“We can’t operate in Singapore,” he said. “We have an office there, but it’s just more or less—there’s one person for our accounting and legal issues.”

Jain declined to speak about why his outfit did not manage to secure a license from regulators. “That, you need to ask them,” he said.

The introduction of the licensing regime in January was cast as the next step in building a thriving crypto sector and set up a contrast with Singapore’s rival Asian financial hub, Hong Kong, which had taken a more skeptical approach to crypto businesses.

A spokesperson for MAS told Nikkei that it is supportive of innovation in the use of blockchain technology, which underpins cryptocurrencies, while also recognizing the risks.

“Cryptocurrencies could be abused for money laundering, terrorism financing, or proliferation financing due to the speed and cross-border nature of the transactions,” the spokesperson said. “Digital payment token service providers in Singapore … have to comply with requirements to mitigate such risks, including the need to carry out proper customer due diligence, conduct regular account reviews, and monitor and report suspicious transactions.”

Rahul Advani, Asia-Pacific policy director at blockchain company Ripple, said Singapore’s stance on digital assets has resulted in the city-state being one of the most advanced and mature nations in the field, helping foster development and innovation in the emerging industry.

“It’s very clear where digital assets and related activities lie on the risk spectrum, so you mitigate the potential of developing and investing in technology that is unregulated,” he told Nikkei.

Crypto players that raced to set up in Singapore run the spectrum from exchange platforms for trading bitcoin, Ethereum, and other tokens, through investment managers and financial advisers looking after digital asset portfolios for the wealthy, to business-to-business outfits helping corporate clients accept cryptocurrency payments.

Outfits that were operating in the country prior to the introduction of the licensing regime were granted exemptions until the outcome of their license application is known. Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam told parliament in July that there were 90 companies operating under such exemptions.

The MAS website showed that the group had shrunk to about 70 as of December 14.

So far, only three players—DBS Vickers Securities, a unit of Singapore and Southeast Asia’s largest bank, DBS Group Holdings; digital payments startup FOMO Pay; and Australia’s Independent Reserve, which offers crypto exchange services—have been listed on the MAS website as licensed entities.

Two others—Coinhako, which operates a crypto exchange platform, and TripleA, a payments company—have put out announcements themselves saying they have acquired the necessary approvals to operate.

Anndy Lian, chairman of Netherlands-registered crypto trading platform BigONE Exchange, told Nikkei that his outfit does not intend to apply for a license in Singapore presently.

“The whole process of selecting who to give the license to is not very transparent,” he said. “It gives the impression that the government is favoring big players and foreign exchanges.”

MAS has not publicly disclosed why specific crypto players were unable to obtain a permit.

But Nikkei understands that some of them did not have the capacity or infrastructure to meet the high compliance standards set out by the financial regulator to deter money laundering and financing of terrorism.

“Cryptocurrencies are currently being used to channel the earnings of everything from ransomware proceeds, the sale of narcotics to some of the most horrific crimes, including human trafficking,” said Rachel Woolley, head of financial crime at client management solutions provider Fenergo.

“Regulators have now entered this space in an effort to protect the financial services industry from illicit activity in much the same way that activity involving fiat currency must be monitored.”

MAS pointed to comments from its managing director, Ravi Menon, who has said that Singapore does not need 160 players in the crypto sector and it may be better to have “half of them” operating at very high standards.

TripleA told Nikkei that in securing its permit, it had to ensure that its operating procedures for risk assessment, customer due diligence, record-keeping, suspicious transaction reporting, auditing, and training were up to snuff.

But its CEO, Eric Barbier, said TripleA gained little insight into what exactly made the difference between success and failure.

“MAS never talks. MAS asks questions and questions and questions,” he said. “You can ask questions but they will not answer, and most regulators are like this.”

Barbier reckoned that being a business serving other businesses may have helped secure a license. “Especially for consumer-to-consumer, like consumer exchanges and so on, the risk of money laundering is very high, so they need to demonstrate to MAS that they are able to mitigate all those risks accordingly,” he said.

Peiying Chua, financial regulation partner for Singapore at the law firm Linklaters, said it is unlikely MAS is specifically favoring big, incumbent financial players: “Likely reasons for unsuccessful applicants may include a lack of track record or key personnel without adequate experience, a lack of a sustainable business model or serious adverse records relating to directors and key individuals.”

“The regulatory approach by MAS may to some degree stifle innovation in smaller entrepreneurs and sift out smaller virtual asset service providers that may not be able to comply with the regulations,” said Quek Li Fei, partner at law firm CNPLaw.

But he added it “provides a more forward-thinking approach toward encouraging legitimate innovation and entrepreneurship in cryptocurrency and digital asset businesses, with a reasonable level of protection to investors.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.