In the world of artificial intelligence and robotics, there’s a well-known principle called Moravec’s paradox. It captures a counterintuitive reality: tasks that appear intellectually demanding for humans, such as logical reasoning or playing chess, are relatively easy for machines, while actions people perform instinctively, like holding a screwdriver and passing it to a teammate, remain extraordinarily difficult for robots.

That paradox is on full display again at this year’s CES in the US, running from January 6–9. Humanoid robots can be seen drawing crowds as they pour coffee, scoop ice cream, and wave for cameras. Behind the spectacle, however, sits a quieter question: when the lights go out and the booths come down, how do these robots move beyond demos and become useful machines in factories, warehouses, homes, and other real-world settings?

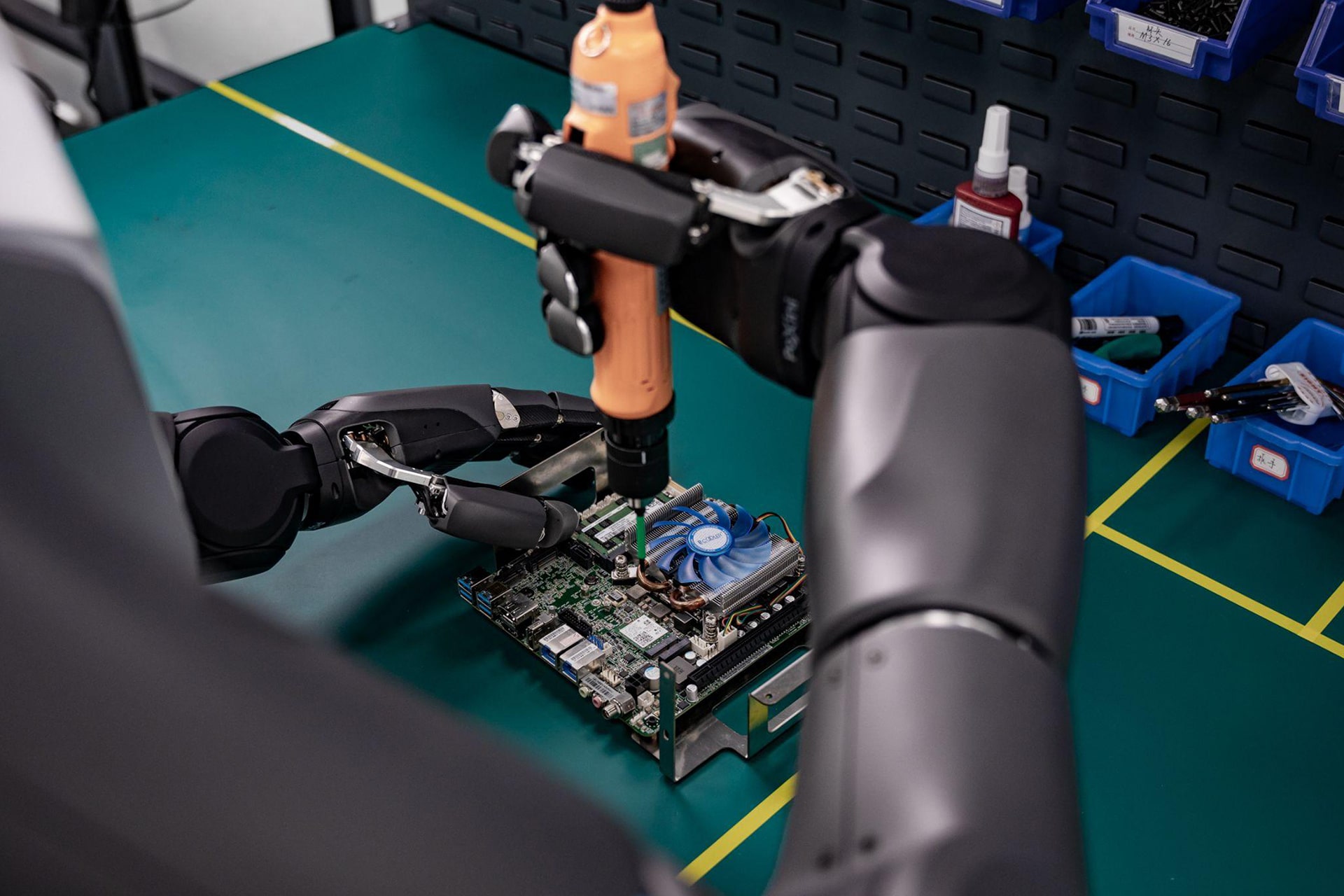

For PaXini Tech, an internationally recognized company best known for its tactile sensing technology, the answer lies in what it calls “full-stack infrastructure” for embodied intelligence. The company is building a foundation that links sensors, data, models, and robot bodies into a single deployable system.

More than a sensor manufacturer

Founded in 2021, PaXini traces its roots to the Sugano Laboratory at Waseda University, often cited as the birthplace of the world’s first humanoid robot. Drawing on what it describes as a pioneering six-dimensional Hall array tactile sensing technology, the company has developed high-precision sensors capable of detecting up to 15 tactile dimensions, including six-axis force, texture, and elasticity. The aim is to give robots something approaching humanlike tactile perception.

According to PaXini founder Hsu Jincheng, meaningful real-world deployment of robotics is not just about vision or planning. It depends on whether robots can make precise judgments and respond in real time during physical interactions involving contact, grip, force, and slip. By continuously interpreting real-time data on mechanics, texture, and motion, Hsu believes robots can develop an understanding of what he described as the essence of interaction. Only when robots are able to “learn” from contact and dynamically adjust their actions on the fly, can embodied intelligence truly evolve from a laboratory concept into a source of reliable, deployable productivity

At CES, PaXini is displaying nearly its entire product lineup, including the PX-6AX series of tactile sensors, six-axis force sensors, dexterous hands, and wheeled robots including TORA-ONE and TORA-DOUBLE ONE. The presentation feels like a physical map of the embodied intelligence supply chain, laid out component by component.

In live demos, the DexH13 dexterous hand, equipped with roughly 1,140 ITPUs, PaXini’s intelligent tactile processing units that function as multidimensional tactile sensors, performs flexible gripping tasks. Nearby, TORA-ONE, a humanoid robot with 53 degrees of freedom and an adjustable height ranging 146–186 centimeters, demonstrates its ability to carry out the full ice cream-making process on-site, showcasing human-like dexterity in tasks such as cup handling, dispensing, and picking up and placing cones.

The message is clear: when a robot can perceive the real physical world, stably control force, and perform various delicate and complex tasks, only then can it leave the lab and enter real environments.

Hsu is careful, however, not to position PaXini as merely a sensor manufacturer. Sensors, he said, are only the starting point. What is far scarcer is the high-quality tactile and force data those sensors generate, data that is needed to train and deploy embodied intelligence systems. Unlike visual data, which scales easily through cameras, or language data, which is widely available online, tactile and mechanical data can only be collected through physical contact. That process is expensive, slow, and complicated by the lack of industry standards.

“What we’re building is infrastructure for embodied intelligence,” Hsu said. PaXini’s strategy is to bridge sensors, data, models, and robot bodies into a single stack designed for real-world deployment.

PaXini positions its products as part of a closed-loop ecosystem built around customers’ needs at every stage of development.

Building a data factory for embodied intelligence

PaXini has built what it calls the world’s largest embodied intelligence data acquisition and model training base, known as the “PaXini Super EID Factory.” The facility reportedly spans about 12,000 square meters and includes more than 150 standardized data acquisition units covering over 15 core application scenarios. The site can reportedly generate close to 200 million lines of omni-modal embodied intelligence data each year, which it plans to make available to global partners through its OmniSharing DB platform.

Yet the company’s advantage isn’t just data volume, but reusability, iteration quality, and multimodal depth.

Most existing datasets are collected through teleoperation, with humans remotely controlling robots while recording motion and sensor states. As robots evolve, adding new joints, actuators, or grippers, older datasets often need to be remapped, reducing accuracy and shortening their useful life. Many robots also lack tactile or force sensors altogether, resulting in datasets that are broad but shallow.

PaXini flips this approach by centering data acquisition on the human body. Operators wear motion capture equipment and generate tactile and force data through natural movement. Because human anatomy does not change the way robotic platforms do, this data remains reusable over time. As humanoid robots increasingly mirror human proportions, the alignment between human and robotic control spaces strengthens, increasing the long-term value of human-sourced data.

This method is also faster and more cost-efficient than robot-based collection, and it captures motion closer to natural human speed.

PaXini focuses heavily on upper-body data, particularly for seated or fixed-position tasks. “Over 90% of industrial work is done sitting or at a station,” Hsu said. “Legs add cost, power consumption, and instability. What determines task success is the upper body, especially the hands and force control.”

At CES, the company has even turned data acquisition into a live exhibit. Staff can be seen performing physical tasks while wearing PMEC, PaXini’s self-developed data acquisition equipment, with real-time motion and tactile data being mapped and displayed on screens behind them.

Expanding the robotic body business

As a global leader in tactile sensors, PaXini initially positioned itself around its sensor capabilities. At the same time, the team began developing humanoid robot platforms early on, in step with the growth of its sensor business.

Hsu said PaXini has incorporated the robot body as a key part of its “infrastructure closed loop,” with the goal of allowing data to drive systems more efficiently while ensuring models can be deployed and run more reliably. Within this framework, sensors and robot platforms operate in close coordination, forming a complete technical chain from perception and decision-making to execution. The company’s humanoid robot platforms are already being validated in real-world scenarios, including large-scale logistics warehouses and automotive manufacturing facilities.

Exporting to the world

PaXini’s presence at CES also highlights its international ambitions. “By tapping world-leading infrastructure and capabilities in embodied intelligence, our strategy is to embed ourselves deeply into global industrial systems,” Hsu said.

The company’s priority markets are the US, Japan, and South Korea, chosen for both scale and structural fit. PaXini sees opportunities in the US, where manufacturing depth and hardware supply chains have thinned, and in Japan and South Korea, where aging populations and slower innovation cycles contrast with strong industrial foundations. The company plans to lead with hardware, embedding its sensors and critical components into customers’ systems, before expanding into data services and model deployment to support automation upgrades.

Looking ahead, Hsu expects that within two to three years, a meaningful number of robots will be operating in real production environments.

As robots move beyond exhibition floors and demonstrations to become reliable sources of productivity in factories and warehouses, the “physical contact modality infrastructure” PaXini is investing in may begin to reveal its true value in reshaping the physical world.

This article was published in partnership with PaXini.