On the evening of July 6, 2020, Sina Corp (NASDAQ: SINA), the company behind microblogging platform Weibo, announced on its website that it had received a non-binding offer of privatization from New Wave MMXV Limited, a holding company held by Sina’s chairman and CEO Cao Guowei.

Sina is not alone in going private. Over the last three months, a total of five listed Chinese companies have officially expressed or indicated an intention to go private. On April 15, Chinese beauty e-tailer Jumei Youpin (NYSE: JMEI) announced that it would be privatized too. Later, on June 15, 2020, Tencent and Black Horse Capital announced that entered into a privatization agreement with Bitauto (NYSE: BITA), a deal that has been in the works since late 2019.

Financial magazine IFR also reported earlier in June that hotel operator Huazhu Group (NASDAQ: HTHT), is planning to take itself private in a bid to return and relist on the Hong Kong stock market, according to the Nikkei Asian Review. When probed by 36Kr at the time of this article, however, Huazhu Group’s spokesperson indicated that it would not comment on market speculations.

In this piece, we take a closer look at what is driving this trend and steps down the road for these newly-private companies.

The logic of privatization

What does it mean to take a company private? Simply put, it means that a majority shareholder raises a sum of money to redeem shares of minority shareholders. Following the redemption of minority shareholdings, the company becomes completely owned by the major shareholder and is therefore delisted from the public exchange.

This is not the first time that Chinese companies have decided to go private en masse and with such stealth.

In 2013, there was a similar flurry of privatizations by listed Chinese companies. This involved giants such as Focus Media, Giant Network, Shanda Games, Perfect World, Qihoo 360, alongside numerous other smaller Chinese companies listed in the United States.

However, Chen Zunde, the general manager of Fande Investment, believes that the round of privatizations that occurred back in 2013 was driven by a slightly different impetus.

“The previous round of privatizations was mainly driven by overall low valuations (in the market) resulting in adjustments to financing structures. Currently, however, privatizations are driven by increasingly stricter regulation in the US markets and the gradual opening-up of domestic capital markets.”

There is clear logic in this reasoning in the face of growing antipathy towards Chinese stocks on US exchanges. For instance, the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, which was passed by the US Senate in May, is a key source of concern. Under this Act, companies may be banned from listing on US exchanges if they fail to comply with audits by the local Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) for three years in a row.

However, compliance with new US oversight laws may pose difficulties to many Chinese companies.

“Critically, after the Luckin Coffee incident, all companies listed in the US need to comply with the compliance and auditing systems of the PCAOB in order to be compliant with the law. However, [such disclosure] is not allowed under China’s own confidentiality regulations,” Huang Lichong, CEO of Huisheng International Capital, explained to 36Kr.

On the other hand, the maturation of domestic capital markets is proving a strong pull factor for companies wishing to relist domestically following privatization.

Hong Kong’s capital markets, in particular, have been historically attractive due to their ability to access global capital with the possibility of a dual-class share structure.

In anticipation of a slew of future listings by returning Chinese companies, Hong Kong’s listing mechanisms are also undergoing further reform to expand the scope of potential shareholders with special voting rights from individuals, and to also include corporations and corporate entities.

Following in suit, mainland capital markets, such as the Shanghai Stock Exchange Science and Technology Innovation Board (STAR) and Growth Enterprises Market (GEM) have started to allow companies with A-class share structures to list as well. In addition, the Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange’s ability to accept variable interest entity (VIE) structures, a commonality among US-listed Chinese companies, can further integrate Chinese exchanges with the international capital market.

Privatization is favored by mid-size companies

Most company’s looking to go private are mid-sized companies. It is simply too costly for majority shareholders to take giant companies private.

“When Alibaba, JD.com, and NetEase returned to China, they chose dual-listings. Because of high capital requirements, it would be difficult for existing shareholders to find sufficient funds to realize a stock redemption (and going private),” said Xu Minsui, a partner at Chenglu Capital.

“However, relatively less capital is required by mid-sized companies when going private. In addition, the US capital markets may no longer be a good source of financing for midsized companies. Listing in two locations also increases fees for the companies, so it may be better to delist (from the US) directly.”

58.com and Bitauto’s privatization deals were said to be worth USD 8.7 billion and USD 1.1 billion respectively. In contrast, if NetEase (NASDAQ: NTES) were to hypothetically de-list and re-list domestically via a privatization route, this would cost its majority shareholders upwards of USD 60 billion (based on the price of its stock at the market close on July 15, at USD 472.21).

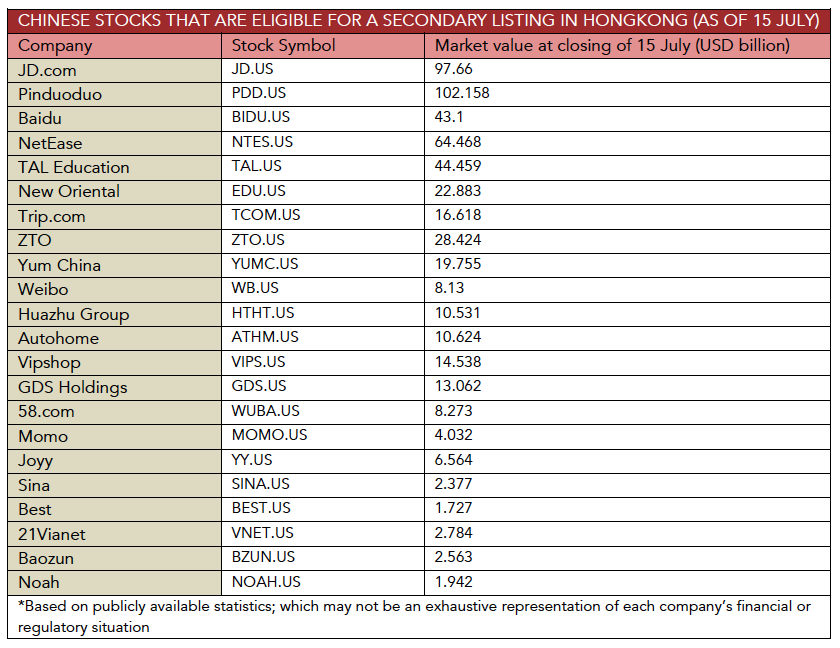

In addition, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange stipulates that companies seeking a secondary listing on its bourse need to fulfill a stringent set of criteria that none but a select set of Chinese companies may be able to fulfill.

Companies seeking a dual listing need to have a good record of compliance for at least two full financial years on a limited number of qualifying exchanges (namely, the New York Stock Exchange, Nasdaq, or premium listing on the London Stock Exchange’s Main Market). In addition, they need to have an estimated market capitalization of at least HKD 10 billion (USD 1.29 billion) at the time of the secondary listing.

If it has an expected market capitalization at the time of secondary listing of less than HKD 40 billion, a company with a weighted voting rights structure, or which has a “center of gravity” in Greater China is also required to have generated revenue of at least HKD 1 billion in its most recent audited financial year.

“Only around 30 (overseas-listed) Chinese companies meet these conditions. If over 250 other listed Chinese companies seek a homecoming Chinese capital markets, going private (first) is the most probable course of action,” said Xu Minsui.

The road ahead is far from smooth

When companies go private, they could either be bidding a complete farewell to the equity capital markets or seeing this as an option for a future relisting in Chinese markets.

Through interviews, 36Kr gathered that future listings in Hong Kong, however, remain the primary reason for this wave of privatizations. However, it will also depend on the particular business needs of each enterprise and the tide of the Hong Kong capital markets system.

It has become almost mainstream for overseas-listed Chinese companies to seek homecoming in Hong Kong’s stock exchange, especially after its reforms.

“At this stage, there is a lot of hot money entering the Chinese market from both domestic and overseas sources. Everyone seems to be speculative and stocks are hot right now. Even if a company’s fundamentals are not good, they still might be able to be listed,” said Huang Lichong.

From an operational perspective, Chinese companies that operate globally and mainly deal in foreign currencies may also be more structurally inclined to a listing in Hong Kong. It is also easier to issue additional shares on the Hong Kong capital market, which may be more appealing to companies that have more frequent refinancing needs.

However, seeking a local listing after going private may not be quite as quick and easy, especially if companies seek a dual-share structure for their future listing.

“There are many Chinese companies that want an A-share structure. In terms of numbers alone, over 200 companies are currently queuing up (for this privilege) on the Growth Enterprise Market. For example, the whole process of Qihoo 360 going private, its application for and return to the A-share market, the demolition of its VIE structure, and then its backdoor relisting took about two years,” cautioned Chen Zunde.

Companies with dual-class share structures, or more commonly known as “A-share companies,” have two designations of common stock with one class having more powerful voting rights than the other. This is commonly preferred in family-run or tech companies where the founding team desires to retain greater control over company decisions, even when economic rights are distributed more widely. Before the recent reforms, such share structures were disallowed in Chinese capital markets.

Despite the optimism over local listings, yet, companies with poor fundamentals may face the ire of investors even upon listing. For instance, a firm’s stock price could fall below its issue price on the very first day of its IPO.

Chen Zunde believes that this may become a norm, as this phenomenon has happened multiply times in the Hong Kong capital market. According to data from Oriental Wealth Choice, of the 165 new listings on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2019, 86 of these new listings had stock price slumping below their issue price on the inaugural IPO day. This accounted for a sobering 52% of listings in that year.

Of course, seeking a relisting is not the only option for newly private companies. Some firms may also choose to go private for other strategic reasons. Elon Musk, for example, has flirted with the idea of taking Tesla (NASDAQ: TSLA) private due to his continued frictions with Wall Street over hitting earnings goals, as well as compliance pressures from ongoing disclosure and reporting requirements.

Alternatively, the stock market may prove counterproductive to companies facing profitability or asset undervaluation concerns. Jumei Youpin, for example, has not publicly conveyed an intention to list again following its privatization in April 2020, seemingly due to its struggles to remain competitive in the face of cutthroat competition.

The original article was written by Chen Zhuo for 36Kr. The English version was adapted by Lin Lingyi.