For Vietnamese fintech startup MoMo, the key to winning the battle against Grab, Sea, and other rivals for the country’s 100 million consumers may be a simple cup of coffee.

Before Vietnam’s latest COVID lockdown, the Ho Chi Minh City-based company ran promotions with some of the country’s biggest coffee chains, including Highlands Coffee, a fast-growing brand with more than 300 outlets. MoMo users got a discount for using the app to place and pay for an order that they then picked up at a scheduled time. The promotion was designed to give them a taste of the convenience of the all-in-one app.

Nudging Vietnamese consumers to use MoMo for even small purchases is part of the company’s strategy to get the app “on the first page of their iPhone,” according to a person close to the company. The thinking is that, in a country where 80% of commerce is still offline, buying a cup of coffee is an affordable and common enough transaction that it will encourage users to open the app daily—or even multiple times a day. That, in turn, could increase the chances of their using MoMo’s other offerings, such as buying movie tickets, ordering food delivery, booking flights, or playing games.

The diverse portfolio of services helped drive revenue at MoMo even during the current COVID wave, CEO Tuong Nguyen said in an interview on Thursday.

“We built a pretty balanced business … so we were confident that even in the very worst case, we will maintain at least 70% [of revenue] of a normal month,” he said. “But of course we wanted to keep growing, so we focused on changing the risks to opportunities.”

MoMo, short for Mobile Money, launched in 2013 and has become Vietnam’s biggest e-wallet. Being an early mover gave it time to cultivate relationships with tens of thousands of offline stores and connect them with the technology to transfer money between bank accounts. Today, it claims 60% of Vietnam’s mobile payments market, processing an annualized USD 14 billion worth of transactions for more than 25 million users, according to the company.

The rise of MoMo, however, has drawn in overseas rivals, helping turn Vietnam into one of Asia’s most competitive fintech markets. Dozens of players, including Southeast Asian tech giants Sea and Grab, have entered the space and are burning cash to acquire users. Analysts predict very few will survive the battle, not just against each other but also against similar services from banks and telecommunications firms.

“The market may eventually consolidate into two or three players,” said Takahiro Suzuki, managing partner at Genesia Ventures and a longtime investor in Indonesia and Vietnam. “But the investors behind them have very deep pockets. As long as the money keeps flowing in, many companies can coexist. It is a painful battle.”

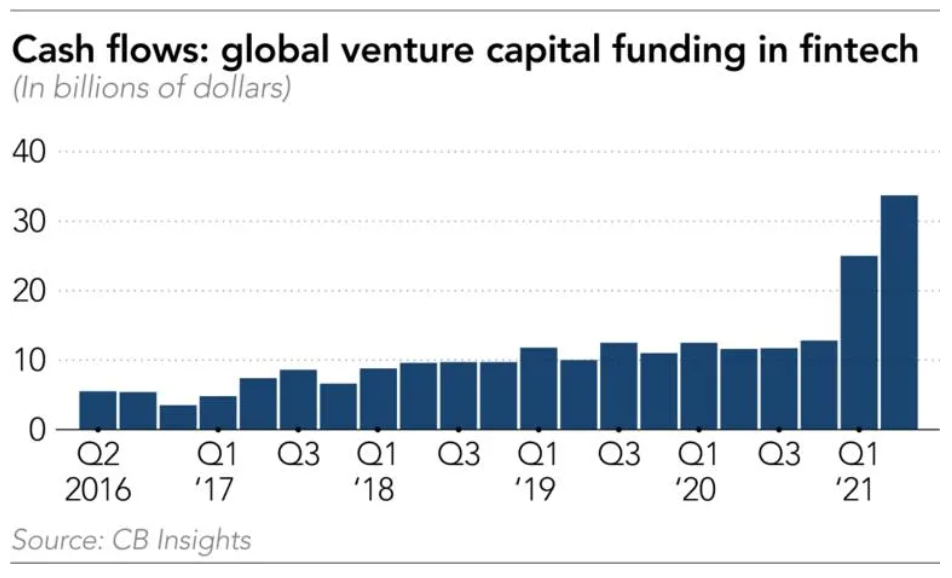

That battle looks set to intensify. VNLife, an operator of mobile wallet VNPay backed by SoftBank Group’s Vision Fund, said in July it raised USD 250 million from General Atlantic, Dragoneer Investment Group, PayPal Ventures, and others.

MoMo, which said in January that it raised USD 100 million from a group of investors including US private equity fund Warburg Pincus, is already considering raising additional capital, according to people familiar with the matter.

In addition to expanding its network of stores that accept the app, MoMo is racing to expand its suite of services, branching out into areas like motorcycle insurance and consumer loans. It has acquired a software company to speed up product development. More deals may be on the horizon if, like other fintech giants in Asia such as China’s Ant Group and India’s Paytm, it pushes to evolve from a payments business into a full-fledged digital bank.

Vietnam has one of Southeast Asia’s oldest startup industries—online gaming company VNG, which now runs the country’s most popular messaging app, was founded in 2004. But the country was eventually overshadowed by its bigger neighbor, Indonesia, where SoftBank and other investors are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into local startups. The surge in Sea’s share price and the upcoming US listing of Grab, which plans to go public via a merger with a special purpose acquisition company, have helped draw broader investor interest to the region.

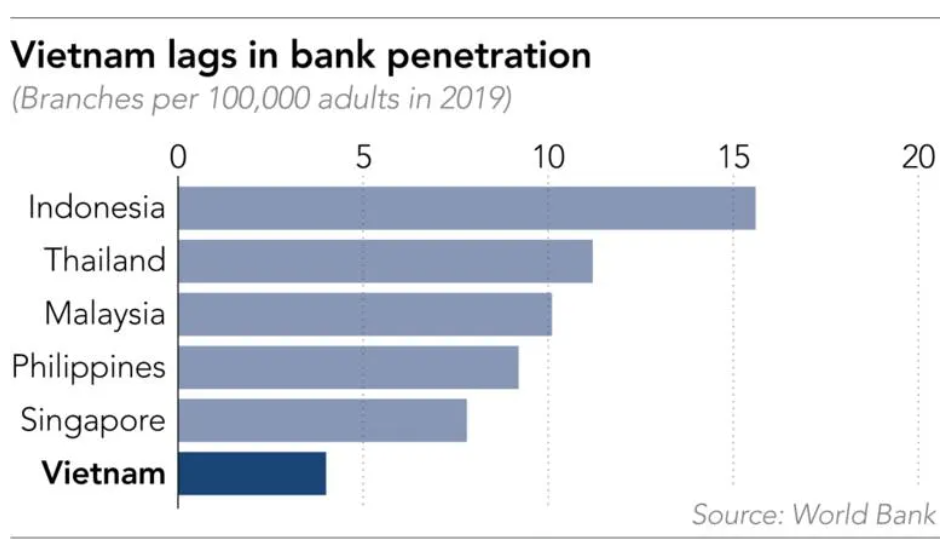

Vietnam’s USD 340 billion economy is also smaller than that of Indonesia, as well as those of Thailand and the Philippines. But investors say its fintech sector is particularly appealing for several reasons. Vietnam has one of the region’s highest mobile phone penetration rates at around 80% of the adult population, but a relatively low number of bank branches per capita. Regulators have shown support for fintech, handing e-wallet licenses to dozens of companies. That combination has created fertile ground for startups looking to deliver financial services via smartphone.

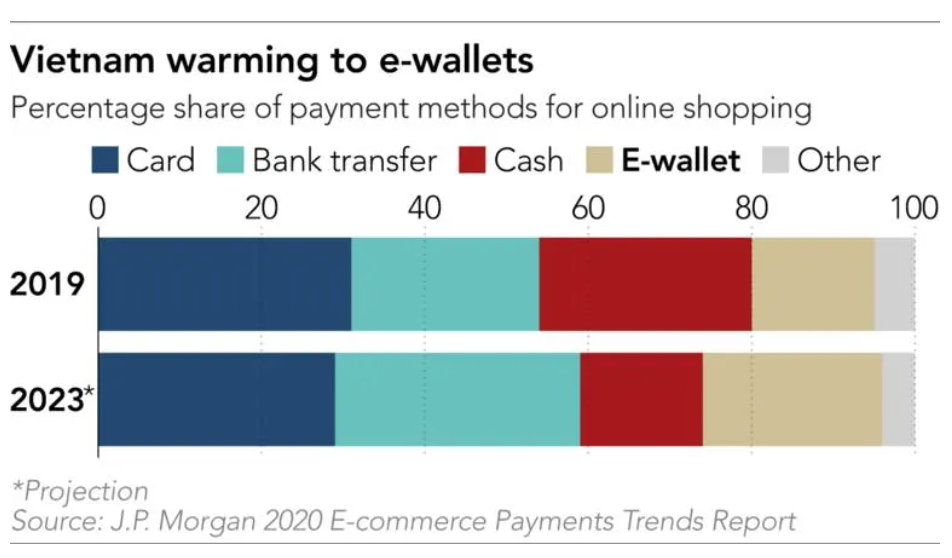

Advocates also say the COVID-19 pandemic has eased a major bottleneck for fintech to take off. Persuading stores to embrace mobile wallets has been a tough task because owners are skeptical about having to pay a fee to mobile wallet providers rather than accepting cash. But Vietnam’s lockdown restrictions have prompted them to look for ways to reach consumers through the internet.

“We’re just at this inflection point, and our view is it’s going to happen much faster than people think,” said a US fund manager. “Smartphone penetration is high, so there is a base of consumers. Now, there are merchants who are coming online.”

MoMo was well-positioned to capture the windfall. Founded in 2007, it was a distributor of mobile phone top-up cards until it saw an opportunity to take advantage of rising mobile phone penetration. The company launched a money transfer app for feature phones and reassigned a part of its agent network, which previously sold the top up cards, to its payments business. The app eventually grew popular among young urban consumers as more of them swapped their feature phones for smartphones.

The problem now, which MoMo executives acknowledge, is that the app’s success has helped attract a flood of formidable competitors into the market.

The biggest rivals include Tencent Holdings-backed VNG, which has been expanding its payment service ZaloPay.

ZaloPay’s “very big competitive advantage” is its link to Zalo, the country’s most popular chat app, said Huy Pham, coordinator at RMIT University Vietnam’s FinTech-Crypto Hub. In China, Tencent used its large WeChat user base to roll out a payment service, which quickly grew into one of the two dominant e-wallets in its home country.

Grab, meanwhile, has partnered with Moca, a local mobile payments company, and made it the main payment option for its ride-hailing and food delivery services. Singapore-based Sea, the gaming and e-commerce company, has launched payments services in Vietnam, too. Sea also operates Now, one of Vietnam’s most popular food delivery apps.

MoMo believes it can beat competition by locking in coffee chains and convenience stores. Young consumers use them more frequently than shopping online or hailing a car, said a person close to the company. “You want to go from someone who is using monthly to weekly to daily, to two to three times a day, because the minute you go to weekly, you become a loyal user that does not churn,” said Manisha Shah, MoMo’s CFO.

Loyalty is low, Pham said. Many Vietnamese download multiple wallets, pulling up whichever has the best discount for the store where they are shopping. The challenge is getting users to continue using an app without lavish promotions. Is that possible? Pham thinks not. He asked his 40 students in one fintech class if they would keep using e-wallets without discounts. All said no.

So he is highly skeptical that any but the biggest e-wallets will be around in five years.

“We have to question why they exist,” he told Nikkei Asia. “They exist because a few years ago the mobile banking system was not well-developed.” But now banks offer most of the same services as e-wallets, which will have to find a way to differentiate themselves, Pham added.

Adding to the threat is a telco pilot program begun in 2021 that lets citizens add money to their phones and then make purchases without needing a bank account.

Analysts say a major potential risk for the entire sector is regulation. Fintech startups have grown partly thanks to a favorable regulatory environment. The central bank says there are 34 e-wallets in Vietnam, though just five have a meaningful level of traction. But sensing a growing threat from fintech companies to the financial system has led some countries to step up scrutiny. Chinese regulators have cracked down on Jack Ma’s Ant Group. In Indonesia, the central bank temporarily stopped issuing new e-wallet licenses, resulting in the most well-funded companies buying companies that already have one.

Another hurdle comes from Vietnam’s rules on initial public offerings. Vietnamese companies listing overseas need approval from the Vietnam securities regulator, while the domestic stock market is small and caps foreign-ownership percentages. In 2017, VNG signed a memorandum of understanding with the US stock exchange Nasdaq to explore a listing there, but VNG has been silent on its progress since. Investors say VNLife may be among the first e-wallets to list, with MoMo following suit, but the path remains unclear. Both companies say they have no plans go public in the near future.

The next few months likely will be key in determining who will survive the shakeout.

“You’re fighting for that space on your iPhone on the first page, right?” said one investor. “Because no one uses five wallets.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.