Key Takeaways

- Last-mile delivery matters to e-commerce success

- Grocery sector is yet to be better digitized

- Digitization comes with a cost that not everyone could afford

With the pandemic lockdowns taking a significant toll on the economies in the region, the general euphoria towards Southeast Asia’s rapid digitalization has quietened a little, giving all of us a pause—amidst a grueling test—to assess how far we have really progressed since the mobile internet revolution in Southeast Asia.

The face of traditional retail and services has changed drastically in the past two months, with business survival crucially tied to the success of the digital transformation of the businesses. As we consider how we can leverage technology to shape the future through digital business, we have identified three main lessons during this period of physical-digital upheaval in Southeast Asia from observing how consumers and businesses have interacted. We have laid them out so that we can all better prepare for the “next normal” in the region.

Lesson One: Last-mile logistics is a critical path to e-commerce success

In the week of 22 March, when a state of emergency was announced in Thailand, shopping app downloads grew 60% in the country, according to data from App Annie. Indonesia, Singapore, and Vietnam, which also had stay-home orders enforced, reported 10% increases respectively.

What ensued was not exactly the triumph of the digital over the physical, but angry customers and workers faced with demand spikes and supply crunches, forcing retailers to suspend deliveries as they were scrambling to catch up on their order back-logs. According to the Malaysian Digital Association, during the third week of March, demand growth rates surged up to 600% for main grocery delivery companies in the country.

Such issues continued through to the usual peak periods, such as the recent Mothers’ Day in Singapore. Failed deliveries, smashed cakes, and cold meals resulted in brands having to apologize to their customers. E-commerce may have hastened the process of digitalization for the region, but the COVID-19 situation poses more problems than online sales channels alone can solve.

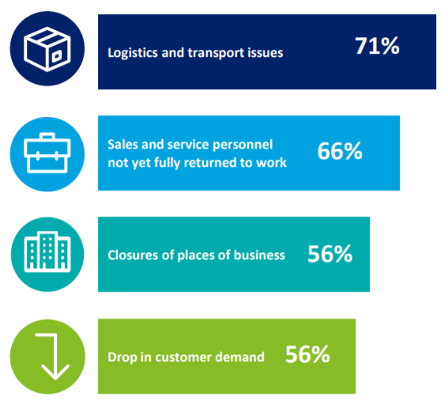

China’s retail scene is a forerunner in this pandemic. Deloitte China and the China Chain Store & Franchise Association’s March 2020 report “Survey on the COVID-19’s Impact on Chinese Retail’s Finance & Operations” may shed some light on the conclusions that Southeast Asian retailers may themselves soon come to: transport and logistics issues are seen as more crucial factors that lead to declining sales revenue during the pandemic than the closure of business places or the drop in consumer demand.

This was especially the case for supermarkets and convenience stores in China. This means that e-commerce businesses must ensure that they have ramped up logistics if they want to continue to build on the opportunities that this disruption has brought about.

Figure 1: Responses from retailers in China on main factors for sales revenue declines, taken from “Survey on the COVID-19’s Impact on Chinese Retail’s Finance & Operations” (March 2020)

Lesson 2: Collective efforts are required for an inclusive digital society

Amidst the frenzy of e-commerce, old-school grocery trucks made a comeback in Thailand. In Singapore, leading supermarket NTUC Fairprice rolled out a new “Fairprice on Wheels” service, bringing supply vans to neighborhoods with a higher elderly population who need easier access to groceries. For all the advancements that a burgeoning e-commerce sector before COVID-19 had brought to consumer habits, logistics, and the payment infrastructure, these vans were basic and accepted only cash payments. Indeed, the urgency of the pandemic requires that we must respond, first and foremost, to fundamental consumer needs.

In a public health crisis, the significance of digitalization is no longer just about keeping up with the times. The potential for subsequent waves of community spread of COVID-19 means that bringing offline segments of the population into the digital order will allow for more flexible contingency measures to be imposed, if necessary. Digitally enhanced operations (when properly executed) can reduce physical human contact to a more situationally appropriate level, allowing everyone to carry on with business with minimized risks of exposure.

Access to groceries is not the only area where we have seen inequalities between population segments surface. With physical schools shut, access to education is now contingent on having smart devices and internet connectivity. In Singapore, as part of our WorldClass commitment to empowering individuals through education and skills, Deloitte worked with local charity Engineering Good to provide laptops for needy students who would need a device to do home-based learning. The use of technology for better education and outreach is a topic that has been discussed for years. What the pandemic has shown us is that while digitalization may break down some barriers, it is still an unlevel playing field and it will need ongoing collective efforts to remedy.

Lesson 3: The economics of digitalization must make sense for all

Between governments and the tech companies that had brought the region into the digital age, much more can be done to help other physical retailers digitalize. Tokopedia’s Satu Dalam Kopi initiative with the government is to promote the coffee industry through online retail; Lazada’s US$2.3 million (RM10 million) fund to help 50,000 local small and medium enterprises in Malaysia embrace digitization; and the Singapore government’s lineup of enterprise assistance packages, all point to an awareness of the hardship for smaller businesses and their corresponding need for assistance. The key to success depends on whether or not these digital arrangements are sustainable in the longer term, after the period of grants and assistance comes to an end.

For digitalization to work, the price must be worth it for all the stakeholders, but this is especially relevant for merchant-users. This issue came to a head with a viral post from a restauranteur who had scrutinized the cost for merchants to use food delivery apps. This was followed by a petition by the Restaurant Association of Singapore that called for lower commission rates from the tech companies operating such apps. This prompted Grab, which offers the food delivery service GrabFood, to respond with a breakdown of costs and commissions to justify its pricing model.

While the pandemic has led to more eateries joining these platforms, others are still not onboard, especially the street food vendors and hawkers who cannot afford to pay the commissions to such platforms. Ground-up efforts are trying to make the economics work for this segment of merchants. From a Facebook group promoting all hawkers in Singapore, to a new crisis startup Locall.bkk using popular messenger service LINE to connect Thailand’s street food vendors with customers and drivers, local initiatives continue to explore cheaper platforms to keep these smaller businesses alive in these difficult times and to enable them to join the digital sphere.

An unprecedented opportunity for long-lasting change

Consumer retail activity has long been a barometer for economic health, and may even be a pulse on societal health. Retail activity under pandemic conditions points to gaps that would need to be filled in order to make the digital economy more inclusive. In these unprecedented times, businesses big and small need to respond fast. For them to thrive over the long run, we posit that the above three lessons present necessary areas to be addressed, even as the region recovers from this economic shock.

About the authors:

Richard Mackender leads Deloitte Southeast Asia (SEA) Innovation, a cross-function, cross-country unit dedicated to driving innovation as a long-term value creator across Deloitte’s Southeast Asia operations. This article was co-written with Chen Liyi and Lim Shu Jun, who are members of the team.