As much of the world went into lockdown last year, most people turned to online shopping, which accelerated e-commerce adoption and increased its share of total US retail sales by 75% last year, growing from 8% penetration in 2019 to 14% in 2020.

Retail giants such as Walmart, Best Buy, and Target saw their market capitalization nearly double in 2020 on the back of enormous e-commerce sales growth. Industries that power the e-commerce ecosystem also heavily benefited from this trend, with companies like FedEx and Shopify seeing incredible growth.

In particular, one industry was a significant beneficiary: “buy now, pay later” (BNPL) solutions saw a massive surge in popularity during the pandemic, as the prospect of delayed payment became more attractive in light of the financial uncertainty resulting from the spike in unemployment.

What are BNPL solutions?

BNPL solutions allow customers to spread out the cost of their purchases into interest-free installments, creating value for both customers and merchants.

Customers: Instead of immediately paying USD 2,000 for a new TV (or paying it a month later in your credit card bill), you can now pay USD 335 a month over six months at 0% interest and no fees, through a seamless checkout experience (fast and straightforward sign-up process, with one-click checkout for returning customers) and flexible payment options (three, six, or 12 months).

Merchants: They witness an improvement in conversion rates, an increase in basket sizes (AOVs), and enhanced repeat purchase rates.

According to Worldpay’s 2020 Global Payments report, BNPL became the fastest growing e-commerce payment method globally, projecting this category to account for 9% of e-commerce payments by 2023 in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

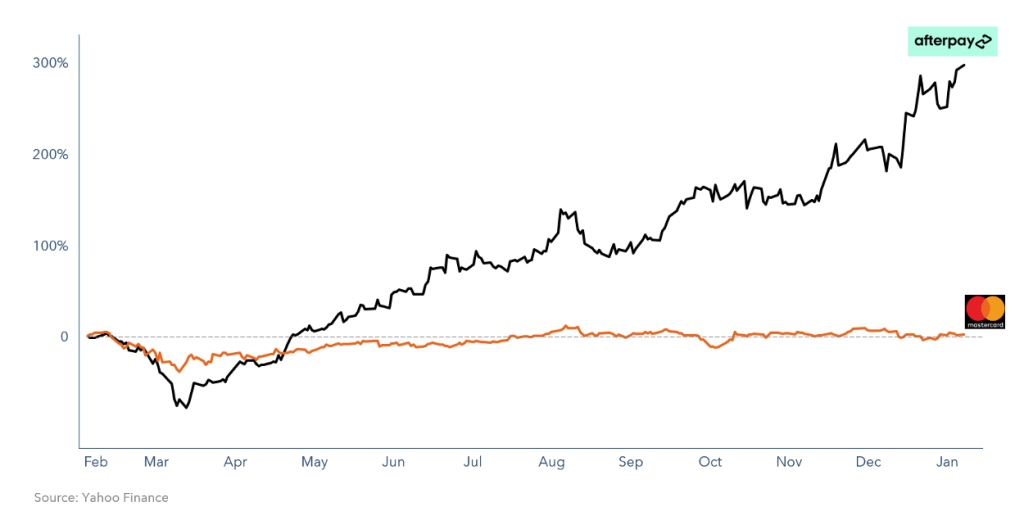

As investors acknowledged the solution’s potential, BNPL providers had a great year, with Afterplay tripling its market cap. Affirm’s value soared by 132% since it began trading in mid-January.

Credit card disruptors

The concept of delayed payment is not new. We all have credit cards, which are de facto “buy now, pay later” tools. Unfortunately, credit cards have remained unchanged for the past 30 years, even though consumers (millennials) developed an aversion to them following the financial crisis and horror stories of extravagant interest rates, like 29% APRs on the outstanding balance.

In essence, credit card providers have gotten lazy and are being disrupted by BNPL players. I wrote about disruption theory last year:

Disruption takes place when smaller, more agile players introduce a lower performing, cheaper product with a structurally different business model. Initially targeting a niche set of customers (lowest value consumers or unserved consumers), they are ignored by incumbents, who instead focus on defending their legacy business model (historically a source of competitive advantage).

As new entrants gradually improve their product, they move up the food chain targeting more attractive customers and stealing market share from incumbents, who, unable to disrupt themselves, see their business models become obsolete, and gradually die.

Compared to a credit card, BNPL solutions are indeed inferior. They can only be used with merchants that integrated into their checkout page. Besides, high spenders can generally cover their credit card expenses and won’t be attracted to BNPL solutions. However, ignoring this trend can be as deadly a mistake as Blockbuster ignoring Netflix at the turn of the century, and we all know how that story ended.

It remains to be seen whether companies like Affirm and Klarna will overtake MasterCard and Visa one day. Given the recent surge in adoption, the macro tailwinds (growth of e-commerce and the millennial consumer), and the growing disinclination towards credit cards, this might happen sooner than we think.

Economics of the BNPL business

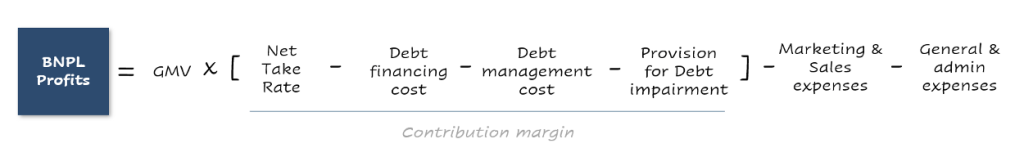

Profitability for BNPL companies depends on seven main metrics and looks something like this:

Net take rate represents the commission charged to merchants (take rate) minus payment processing fees that the BNPL company pays.

Debt financing cost corresponds to the interest BNPL providers pay banks for liquidity (to provide loans to their customers).

Debt management cost equals the credit check costs plus payment collection costs minus late fee payments collected from customers.

Provision for debt impairment equals the weighted average percentage of loans that are not paid back, i.e. bad debt.

The four above components represent the contribution margin. In their early days, BNPL companies tend to have a negative contribution margin as losses incurred from debt impairment wipe out any income generated. However, over time, BNPL players use data to improve their algorithms and remove “bad customers” from their platform, reducing such losses.

Let’s look at an example: Suppose your net take rate is 5%, assuming merchants pay you 6% and you pay 1% in payment processing fees. If you pay 1% interest on your loan, and it costs you 1% to manage consumer loans, the percentage of your non-performing loans can’t exceed 3%; otherwise, you lose money. Unfortunately, this figure is generally higher in the early years and remains so for a while.

GMV refers to gross merchandising value, the sum of all payments conducted on the BNPL platform.

Marketing and sales expenses are expenses incurred as BNPL providers acquire and bring on board merchants and customers to their platform.

General and administrative expenses include team salaries, technology, and other infrastructure costs.

Turning profits in BNPL is very tricky, and the model relies heavily on economies of scale, i.e. a high GMV, which enable companies to:

- Negotiate better terms with financial institutions (banks) and infrastructure providers (payment systems).

- Access more data to improve their algorithms and reduce losses from debt impairment.

- Balance out the high fixed costs of the business (marketing, salaries, technology, and infrastructure).

Consumer-merchant flywheel

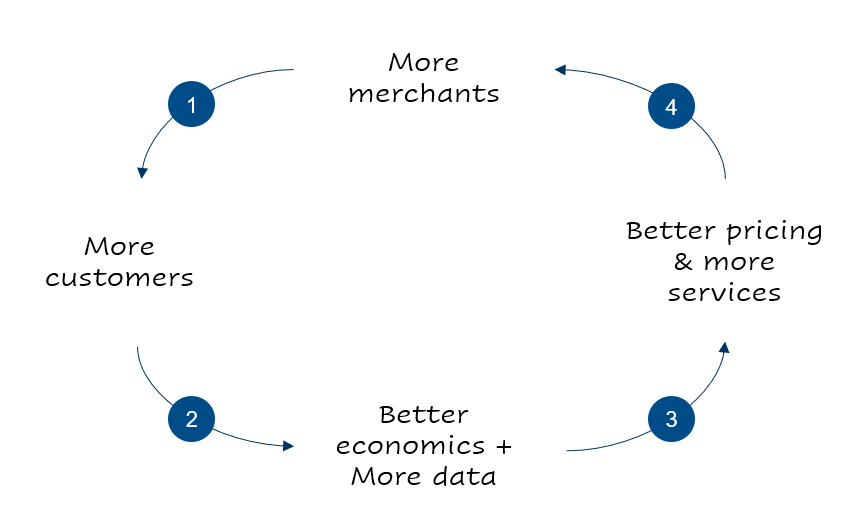

Beyond profitability, the BNPL economic model relies on a positive feedback cycle (flywheel) that helps winners keep winning.

As more merchants join a BNPL provider, more consumers have the opportunity to use the service. As these consumers see the service across multiple platforms, they trust it more and are more inclined to try it, leading to more transactions.

More consumers lead to more transactions and higher GMV. As a result, BNPL providers increase their profitability (economies of scale) and improve their risk assessment capabilities and algorithms, thus dropping their loan losses (debt impairment).

Improved economics enables BNPL companies to offer more attractive deals and better services to merchants, i.e. conversion optimization and other services based on data collected.

Better deals and services make the BNPL value proposition more attractive to merchants, increasing overall adoption and attracting more merchants.

BNPL in the Middle East

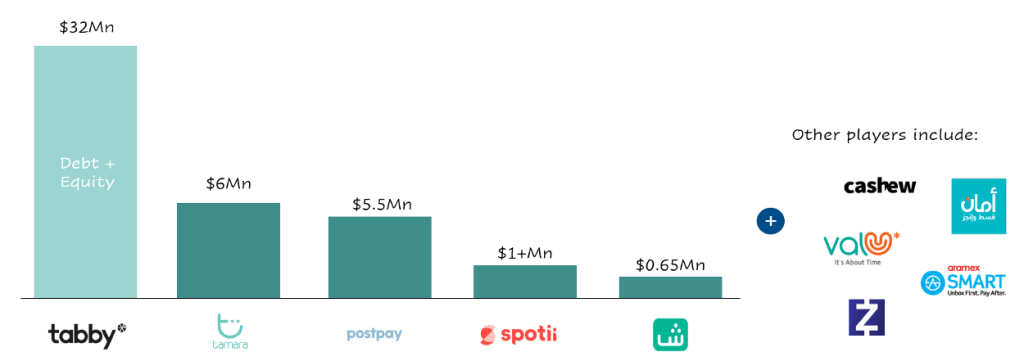

The Middle East region has witnessed an explosion of BNPL solutions in the past year, with 10+ providers emerging, many of whom have already raised significant funding to explore the space.

Beyond improving conversion and sales, regional BNPL providers offer something extra: partial relief from cash-on-delivery (COD) issues. Cash-on-delivery, which accounted for more than 60% of payments for e-commerce sales pre-pandemic, has been a major obstacle for e-commerce growth in the region and a headache for merchants. BNPL solutions allow customers to pay after delivery, thus partially driving some of them away from COD and removing the collection burden from merchants.

As a result, I expect this service to rapidly gain traction in the Middle East. However, the industry is likely to undergo some major shifts over the coming years as we see four key changes taking place:

1) Not everyone will survive.

As discussed above, the economic model or flywheel effect in BNPL means that succeeding in this business depends on your ability to:

- Grow GMV and achieve economies of scale.

- Raise enough money to cover losses in the early years of growth, as you work to yield a positive contribution margin and cover your fixed costs.

As a result, we will see consolidation in the market, as smaller players fail to achieve the required scale or raise enough money and thus exit the space (or are absorbed by some merchants). Eventually, two to three independent players would survive and grow, each picking a specific category or geography to focus on.

Given all players offer roughly the same core product, distribution will be the core driver predictor of success in the first phase of growth: Whoever secures the highest number of quality retailers first will build an advantage.

2) Taking the battle to the consumer.

As merchants start offering more than one BNPL solution, providers will very soon look to the other end of the marketplace—the consumer—to capture the transaction.

They will redirect their marketing budget toward offerings aimed at keeping the consumer loyal to their platform. As a result, expect to see more customized products and value-added services for consumers. Eventually, BNPL providers will turn their websites into shopping and discovery platforms with merchant discounts to attract first-time customers. In that respect, BNPL apps and websites become a mini-version of The Entertainer, which runs buy one get one free offers for luxury and high-value purchases.

Shahry is a pioneer in this area and has already taken steps in this direction as it enables customers to browse various products and checkout on the Shahry app itself, providing a seamless experience and ensuring you capture the consumer before they get to the checkout page. ValU, the first in the region to offer BNPL, is owned by EFG Hermes and has also embarked on the same journey.

Also, similar to what western companies are doing, regional BNPL providers will offer virtual cards, where consumers pre-add money to use in their online and offline purchases, thus keeping them loyal.

3) More regulatory scrutiny.

Consumer lending is one of the most regulated sectors in our region. As they grow, expect BNPL providers to attract a higher level of scrutiny. Regulators will specifically be worried about the adverse selection effect of the business:

Many BNPL consumers opt for the service as they can’t afford to pay for their purchase fully. These consumers will be at a higher risk of defaulting on their loans and getting burdened by debt. Regulators will look for ways to protect them and won’t look lightly at BNPL providers using tactics that incentivize impulse purchases.

4) Some response from traditional players.

Given the low barriers to entry, there is no reason why big e-commerce players, like Amazon or Noon, and big retail conglomerates, like MAF, Chalhoub, and Al-Futtaim group, can’t start offering their own BNPL upon checkout. They may even buy the smaller players in the space as I mentioned in trend (1) above.

Similarly, banks might learn a thing or two from disruption theory and start providing a credit card suite with a similar structure. In the US, JP Morgan Chase has recently entered the BNPL space, offering consumers the option to pay for purchases over multiple months at 0% interest and a small monthly fee.

Regardless of how things play out, the future looks bright for fintech players in the region—especially for BNPL providers.

This article was written by Imad El Fay. It was first published by MENAbytes.