When Indian online education platform Byju’s became a USD 1 billion company in 2018, it made global venture capital (VC) firms sit up and take notice of the rapidly growing edtech market in the world’s second-most populous country. Till then, edtech was an underdog in the Indian startup ecosystem.

Getting the much-coveted billion-dollar valuation was just a beginning for India’s first edtech unicorn that started as an offline tutoring institute in 2011 by a locally famous teacher, Byju Raveendran.

In a meteoric rise, Byju’s valuation jumped from USD 1 billion to USD 10.5 billion in mere two years. To date, it has raised about USD 1.5 billion from global investment firms like Sequoia Capital, Lightspeed Venture Partners, Qatar Investment Authority, Tiger Global, General Atlantic, Naspers, Tencent, and Bond, among others.

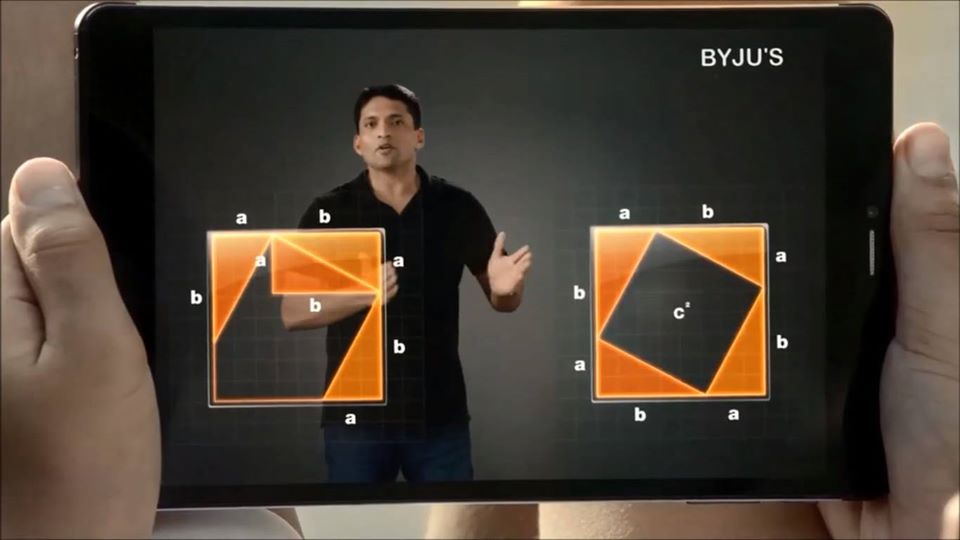

Over the years, the company that currently offers online learning courses for grades 1 to 12 (or K-12) and preparation courses for competitive exams, went through multiple changes, the biggest being shifting from physical tutoring to online courses.

Read this: Byju’s acquires coding tutoring startup WhiteHat Jr for USD 300 million

Along the way, the Bengaluru-based company has emerged as the world’s most valuable online education company, well ahead of the most-talked-about American edtech company Coursera that started at about the same time by two Stanford professors to offer online courses by top universities.

However, Byju’s journey hasn’t been without bumps. Time and again, the company has been criticized for its alleged sales-centric approach, toxic work culture, badgering parents into buying courses, and poor customer service. Despite all that, the company remains undeterred and is aiming to replicate its success in the domestic market in other countries.

To achieve its grand vision, Byju’s has raised USD 400 million this year alone and is reportedly in talks with DST Global for an additional USD 400 million.

The accidental entrepreneur

Over the last 15 years, Raveendran has pivoted from being a mechanical engineer to a teacher to a hard-core technology entrepreneur. People who know him do not shy away from calling him a genius. For a person who has cracked CAT, the common assessment test for entering India’s elite management school (IIM), with 100 percentile, without any preparation, he is undoubtedly more than just hands-on smart.

Hailing from Azhikode, a small village in the Southern state of Kerala, Raveendran comes from a family of teachers. In the early 2000s, he landed a cushy job at a multinational shipping firm, which required him to travel around the world as a service engineer. During one of his vacations in Bengaluru in 2003, he helped some of his friends prepare for CAT. Many of them ended up clearing the test with flying colors, along with Raveendran who took the test for fun.

Two years later, when he came back to the city, a larger pool of students came to study under him. The number kept growing, and the venue of this study group moved from the terrace of a friend to a classroom, to an auditorium.

In a 2016 interview with Rediff.com, Raveendran said during the six weeks he spent in Bengaluru, he “might have trained more than 1,000 students.” It was then he discovered his knack for teaching and decided to leave his high-paying job to start a CAT tutoring institute.

In the first few years, Raveendran was traveling to multiple cities in a week, to take classes. With growing numbers of students wanting to learn from him, a few times he had to take classes in stadiums. By 2009, he had begun pre-recording his lectures and offering them to students in 45 cities, milking the Byju’s brand that he had established.

In 2011, along with some of his former students who had come back after finishing their MBA from IIMs, Raveendran set up a company called Think and Learn to run classes under the brand Byju’s. This was the foundation for the multi-city offline coaching class chain for competitive exams that offered classes and course material along with Raveendran’s video lectures.

The making of a Goliath

Think and Learn was bootstrapped by Raveendran who had put in over USD 2,500 from his earnings. One of the first things that Raveendran did after setting up the company was to put together a team to create learning content for school children in grades six to 12. Meanwhile, the company grew its hold in competitive exams, which had been its cash cow all along.

This essentially means that from the very beginning, he focused on capturing the mass-market opportunity–the K-12 segment that has over 250 million school-going children.

When Ranjan Pai, co-founder of VC firm Aarin Capital, learned about thousands of students taking Byju’s video classes for CAT, he invested USD 9 million in the company in 2013.

This funding round, helped the company to catalyze product development in the K-12 segment, and enabled the teacher-turned-entrepreneur to execute a strategy around mobile devices for students to consume content anywhere, anytime.

In 2014, the company which was operating offline till then, launched tablet learning programs for competitive exams and grades eight to 12 that offered the entire learning content in a video format on tablets along with doubt clearing classes.

While Byju’s saw its fortune grow between 2011 and 2014, it was a dark period for the first breed of edtech startups that hoped to replicate the success story of Coursera in the country.

According to Anil Joshi, managing partner at Mumbai-based early-stage VC Unicorn India Ventures, who had invested in a couple of e-learning startups almost a decade ago, the Indian education technology companies offering learning courses online were facing two issues–poor data connectivity and the limited availability of devices on which students could consume the content.

Investors thought it would be a long shot for Indian edtech companies to earn money from selling learning content online, so a lot of them went back on their promise to write checks, forcing many edtech startups to either shut shop or pivot.

Raveendran, it seems, had stuck with the offline approach for this very reason. Moreover, he launched tablet learning program to sidestep the issues with connectivity and devices, and waited for the right time to make his online debut.

The online avatar

In the summer of 2015, Byju’s got Sequoia to invest USD 25 million in its Series B round of funding. A month later, Raveendran rolled out Byju’s learning app targeting school students, which amassed two million users within a quarter.

Over the next year, things finally started coming together for Byju’s. With Reliance launching its telecommunications venture Jio Infocomm and splurging on offering data plans at dirt-cheap rates, internet became available at affordable prices for masses. At about the same time, smartphone penetration started to expand as Chinese giants like Xiaomi, Oppo, and Vivo launched high-specification devices at cheaper prices.

As the internet and smartphones started getting affordable, Byju’s began its transformation from an offline tuition center to an online education company.

“He had been very observant, and he came online when the timing was right,” said Joshi.

By 2016, Byju’s had roped in almost 250,000 paying students overall (online and offline). As it raised a subsequent round from Sequoia and saw its influence grow beyond metros, the company landed a check of USD 50 million in its Series D round in September 2016 from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative – the philanthropic initiative of Facebook’s co-founder Mark Zuckerberg and wife Priscilla Chan. Zuckerberg’s backing catapulted the company to stardom in the Indian startup ecosystem.

Apart from the right timing, what worked in Raveendran’s favor, according to industry watchers, was his fame as an educator.

Read this: Investments in edtech companies shine in the first half of 2020

In 2017, Raveendran played another card that proved extremely crucial in bumping up the company’s brand image and valuation. He convinced Bollywood actor Shahrukh Khan to be Byju’s brand ambassador and spent money like water in marketing initiatives.

“Onboarding Shahrukh Khan in its early days was a bold move,” Joshi observed. “First, it is very expensive. Second, to convince a brand like Shahrukh in those days for a startup was very difficult because brand ambassadors are equally concerned about their image.”

According to Joshi, Byju’s ability to raise money from the likes of Sequoia and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, a large user base, the first-mover advantage, the right brand ambassador, the perfect timing to come online, and applicability of its solutions to be expanded internationally, “went in its favor.”

And these very factors set the company apart from other edtech firms like Toppr, Unacademy, and Vedantu. However, as Byju’s validated the business model, it helped other edtech companies to raise funds, Joshi believes.

By early 2018, Byju’s had entered the coveted unicorn club. Later that year, when it raised a whopping USD 540 million round from Naspers Ventures and Canada Pension Plan Investment Board at a USD 3.6-billion-valuation, it became the world’s most valuable edtech company. It reportedly achieved USD 10.5 billion-valuation when Bond invested an undisclosed amount earlier in June.

The company claims to have 57 million app downloads and 3.5 million annual paid subscribers as of now. Currently, students can buy courses in the mode that they prefer. They can either choose to stream content on the app or get an SD card with video content or opt for an SD card with a Lenovo tablet. Its offerings across categories range from INR 24,000 (USD 320) to INR 160,000 (USD 2,137).

If these numbers are to be believed, the company can clock at least USD 1.1 billion in revenues for FY21, if it doesn’t offer any discount. While Byju’s has a long-term global expansion plan, it’s currently busy acquiring its peers in India to expand its market share in the crowded edtech space.