This article first appeared on Nikkei Asian Review. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei. 36Kr is KrASIA’s parent company.

BANGKOK — Asian IT visionaries have built billion-dollar empires with staggering numbers of users. But one thing they have not done is create a killer app that is truly used worldwide. Even giants like China’s Alibaba Group Holding and Tencent Holdings mainly cater to local or overseas Chinese consumers and companies.

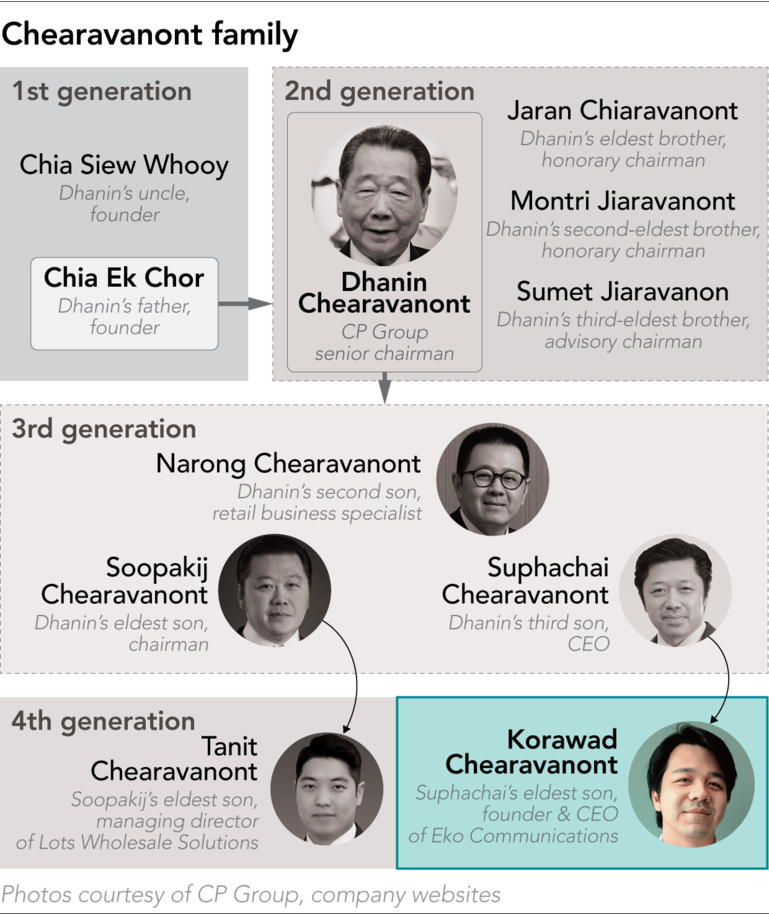

Korawad Chearavanont — a grandson of Thailand’s richest tycoon, Charoen Pokphand Group Senior Chairman Dhanin Chearavanont — wants to be the one to change that.

It will be anything but easy for the 24-year-old. His Eko Group, which runs an eponymous mobile communication app for workforces, hopes to fill gaps in the so-called enterprise collaboration market left by the likes of Slack Technologies, a US chat app company that earns somewhere around 40 to 50 times as much monthly revenue and just had one of the year’s most successful stock listings in New York.

Microsoft and Facebook are also fighting over the same global workplace collaboration software market, which is projected to approach USD 17 billion by the middle of the next decade.

Art Schoeller, an analyst at Forrester, said “there are niches and slices” of this emerging market that new startups can grab. But he also stressed he highly doubts that smaller players can “overcome the big gorillas.”

And yet, Korawad is convinced he has a shot. “The market is really open right now,” he told the Nikkei Asian Review. “The kind of growth we are experiencing in the US and in Europe is really, really exciting. I think Eko has so much potential.”

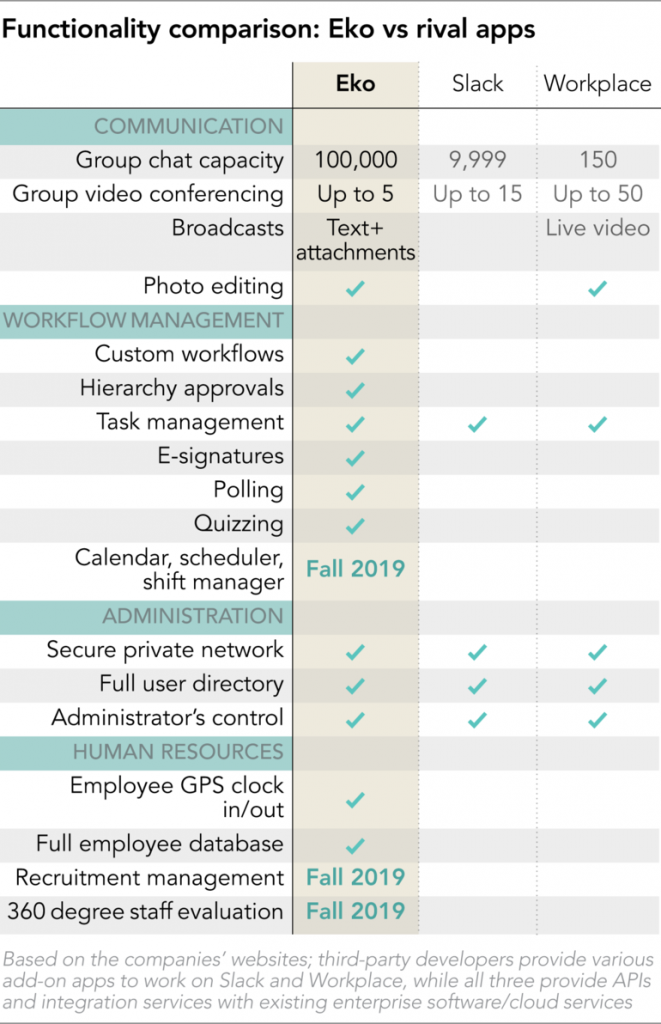

One way Eko aims to catch up is by offering features its big-name US rivals do not.

Facebook’s Workplace allows an organization to run group chats with just 150 employees at once. Slack’s platform allows more — 9,999. But Eko beats them both by a huge margin, accommodating up to 100,000 users in group chats simultaneously.

Eko’s biggest customer so far is a US multinational that has nearly that number of workers globally. The company declined to name this client, but other major users include Telekom Malaysia and Thanachart Bank, Thailand’s sixth-largest commercial bank, along with London-based nonprofit One Young World.

Korawad sees his app as a platform for all kinds of front-line, mobile workers in large enterprises. On top of sheer user capacity, Eko provides a suite of functions to manage workflows, tasks and human resources. It includes features optimized for industries such as retailing, wholesaling, hospitality, manufacturing and health care, along the lines of major enterprise resource planning software such as SAP and Oracle ERP — applications that help manage inventories, payrolls and other critical operations in real time.

These functions are “what really sells,” Korawad said.

To attract hotels, Eko partnered with Command Line Software of the U.K., which provides “connector” software that links up with ERP systems used by major hospitality chains. This way, an employee using Eko can access data in their hotel’s main management system.

U Hotels & Resorts — a Bangkok-based luxury chain with locations in Thailand, Indonesia and soon Vietnam — has embraced Eko’s management tools. About 130 employees at a hotel in the Thai capital have been using the app for two years. Messages zip between them to keep everything running smoothly. Managers use Eko to deploy staff to busy areas or, say, make sure there are enough napkins for lunch.

“With Eko, we can manage staff resources 100%,” said Markus Schneider, the hotel’s general manager. “Who is in, who has newly joined the hotel, who has left the company and so on.”

The U Hotel also uses Eko for performance evaluations. Supervisors can give staff a “thumbs-up” for teamwork, innovation and kindness. An employee receives a 1,000 baht (USD 33) bonus once he or she has accumulated 10 of them.

Korawad thinks his service fills a unique niche. The closest things may be the mobile chat-based enterprise software of Alibaba and Tencent’s WeChat, which Eko regards as benchmarks. “Outside China, we really have no direct competitor,” Korawad said.

Yet there is no escaping comparisons with Slack, which has taken the global business messaging market by storm over its 10 years in existence.

The US company counts over 10 million active individual users a day from around 600,000 organizations, combining its free and paid services. As of April, about 95,000 companies were paying customers.

Slack’s direct listing on June 20 gave it an initial valuation of over USD 20 billion. Eko, meanwhile, is not even close to unicorn territory — a startup valued at USD 1 billion or more.

Eko is growing faster than Slack, but this is attributable to their different stages of development. Slack’s revenue grew 66% to about USD 135 million in the quarter to April, down from over 80% for the full year ended January. The US company reported a net loss of USD 138.9 million for the year, almost unchanged from the year before.

Meanwhile, Korawad said Eko is achieving 250% annual revenue growth, without disclosing specific figures. He did reveal that his app has 200 customer organizations with 700,000 individual users on paid plans, which range in price from USD 1.50 to USD 3 per user a month. This suggests Eko, which is also loss-making, brings in only a fraction of Slack’s revenue.

The question is whether Eko can make up ground as global demand surges. US-based Grand View Research says the team collaboration software market — which includes chat, shared calendars, project management and file-sharing — will almost double to USD 16.6 billion by 2025 from USD 8.9 billion in 2018.

While Korawad is laser-focused on the collaboration market, his father and grandfather oversee businesses ranging from poultry to convenience stores and mobile telecommunications.

Korawad is the eldest son of Suphachai Chearavanont, CEO of CP Group. Korawad’s grandfather, Dhanin, led CP into China and turned it into Thailand’s biggest conglomerate. Dhanin told Nikkei in June that any of his grandchildren, including Korawad, could be candidates to become chairman or CEO one day.

Nevertheless, Korawad offered no hint that he wants to take over the family business. “There is no chance that I become skilled enough and qualified to run such a giant conglomerate like CP Group for the next 30 years, so there is no point in thinking about it.”

Likewise, he is quick to distance himself from the family fortune, saying Eko received “not a dime” from CP Group in its fundraising rounds.

While CP companies use Eko, he insisted they were late adopters that chose the app for “purely economic” reasons. Eko’s clients include True Corp., which ranks No. 2 in Thailand’s mobile telecom market and where Korawad’s father serves as chairman, and CP All, which runs 7-Eleven convenience stores in Thailand.

Eko would not disclose how much revenue comes from CP companies.

“Since I was young,” Korawad said, “I was always told it is our family rule that each member has to go and do his or her own thing, build something new.”

He founded Eko Communications as a mobile chat app in spring 2012, when he was 17 and attending boarding school in New Jersey. Upon graduating the following year, he told his parents he would rather focus on his startup than take the place Columbia University had offered him.

They made a deal: Korawad could quit college if he raised USD 5 million from major venture capitals.

In August 2015, Korawad raised a little more than that in a Series A funding round led by Gobi Partners, a venture capital firm headquartered in Shanghai. This was on top of the over USD 1 million Eko had already collected in seed-round funding from investors including 500 Startups, a US fund that backs early-stage ventures.

Having met his parents’ terms, Korawad quit Columbia and moved back to Bangkok to concentrate on Eko.

“I am grateful to my parents greatly for setting that bar for me, because it was such a difficult but great learning process to go through all those steps of pitching, getting rejected, pitching again and again, and finally getting funding,” he said.

In November 2018, Eko closed a USD 20 million Series B funding round led by Sinar Mas Digital Ventures, an arm of one of Indonesia’s biggest family conglomerates. Other investors included AirAsia’s digital investment fund and EV Growth, a joint venture set up by East Ventures of Indonesia, Sinar Mas Digital and Yahoo Japan Capital. Japanese trading house Itochu also invested USD 1 million before the Series B.

Eko has now raised a total of USD 28.7 million.

Underscoring his global ambitions, Korawad used the money to move Eko’s headquarters from Bangkok to London in January, though he kept his development base in Thailand. Eko is also setting up a European engineering hub in Portugal while expanding its marketing team in Austin, Texas, to cover the US market.

“It is very important to provide location options to attract and retain good talent from around the world,” Korawad said. His team in Bangkok comprises more than 20 nationalities. “Few of them think Bangkok is their eternal home.”

Eko is now building Japanese engineering and business teams to prepare for a launch in Japan in 2020. The global head count reached 125 in June, up from 45 at the beginning of 2019, and is expected to top 200 by the end of next year.

Korawad acknowledged that Slack, Facebook and Microsoft can all crank up investment quickly, adding new features and making the competitive environment even harsher.

Sure enough, Microsoft has been releasing add-ons for its Teams app to help with personnel management, including staff scheduling and a “praise” tool akin to Eko’s thumbs-up.

Korawad knows Eko has a lot of work to do, and that it needs to act fast before the giants become direct competitors. Still, he is optimistic.

“There is a long way to go for us,” Korawad said. “But even for Slack, they are still losing money. They have a long way to go, too.”

Nikkei staff writer Marimi Kishimoto in Bangkok contributed to this article.