One year ago, grocery e-commerce wasn’t a particularly hot service in China. For consumers, stops at neighborhood markets were preferable—do these tomatoes have just the right firmness? Is this watermelon ripe enough? Surely, there’s a fresh cut of pork loin at the butcher’s stall. It is important for many people to touch and squeeze and tap the produce with their own hands. This is particularly true in smaller cities and village, where same-day and next-day delivery options are limited or nonexistent.

The nature of online grocery shopping made it difficult to execute. Food storage and transportation has strict requirements, fresh produce carries slim profit margins, and low transaction volume per customer made it nearly impossible to pull off satisfactory unit economics. It wasn’t clear how moving the process online—into apps or websites—would build a profitable process.

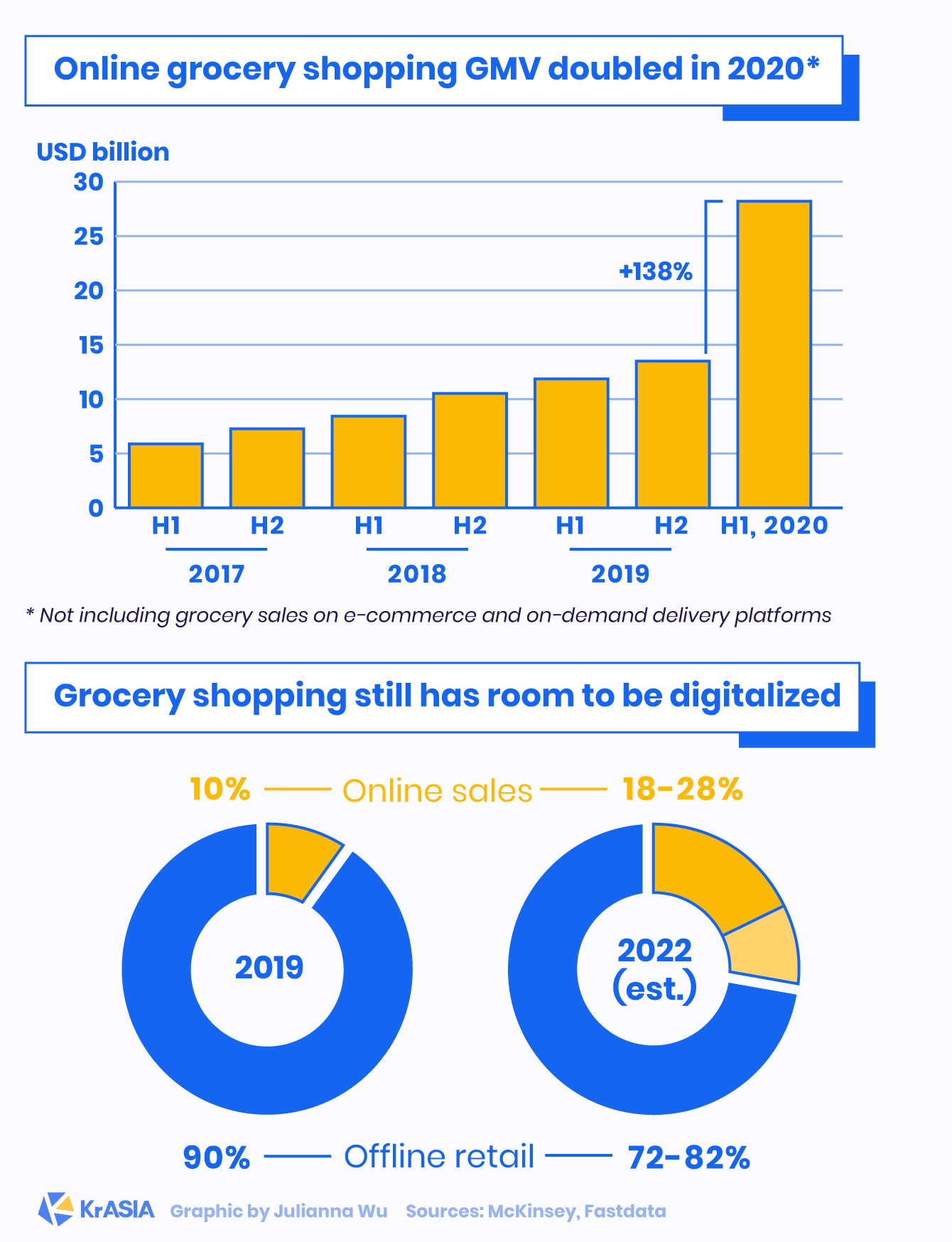

But the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything. The fundamental conditions for efficient online grocery shopping are now in place. In just the first two months of 2021, the amount of funds raised by the sector’s operators has already surpassed the investment sum of all of 2019, with the average deal size running at more than USD 460 million, per data from ITjuzi.

China’s annual grocery retail volume is expected to hit USD 1.04 trillion in 2022, with online sales accounting for less than 28% of the transactions, according to data compiled by McKinsey and Euromonitor. That’s nearly triple 2019’s online share of 10%, hinting at a major business opportunity if newly developed habits stick.

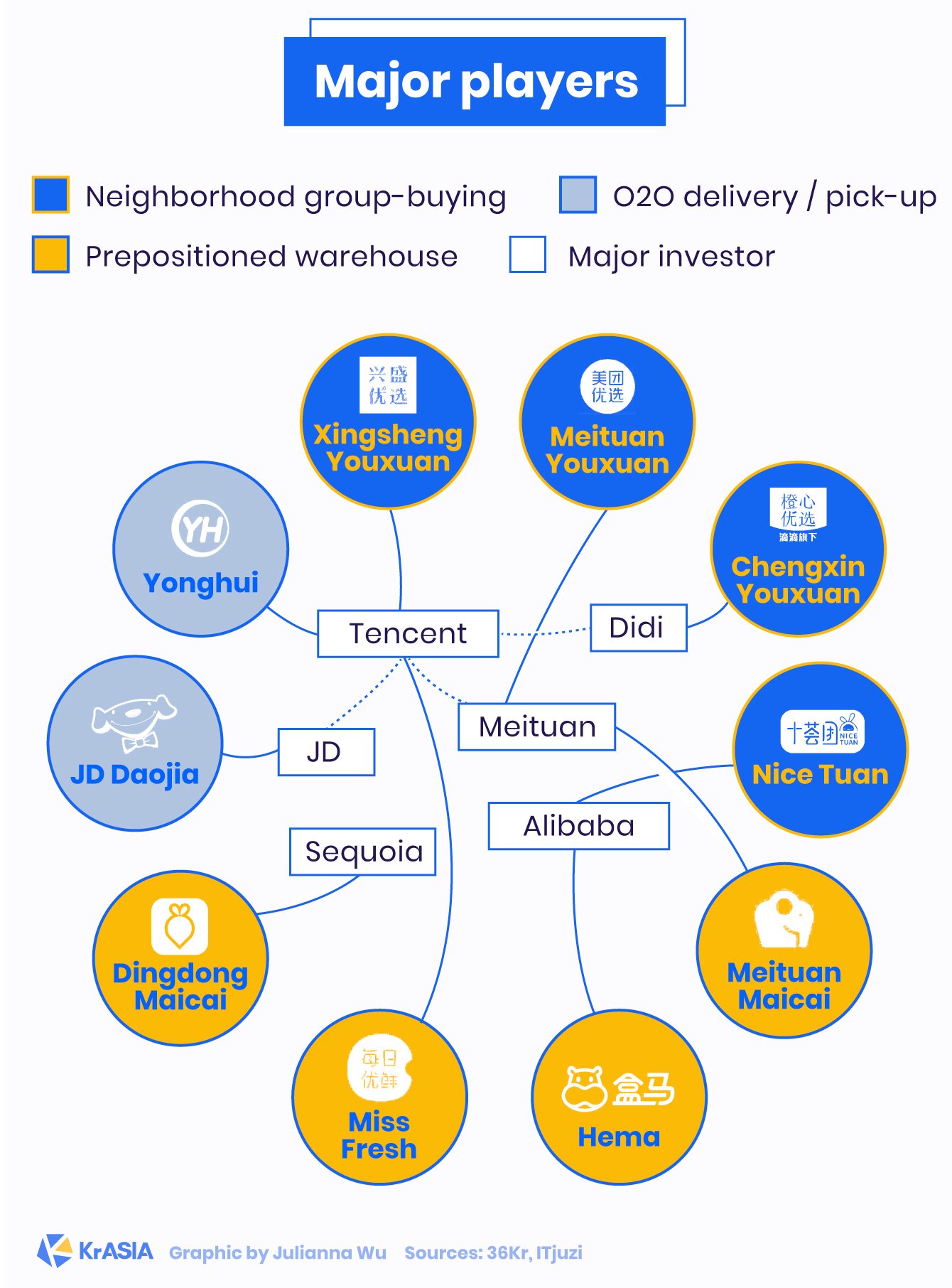

The grocery e-commerce sector is still chaotic. There are over ten startups and internet giants operating in the space, and they run at least three different business models. That means these services are works in progress, and this billion-dollar market is still up for grabs.

Current solutions

Online grocery shopping isn’t new in China. In the early 2010s, startups and tech companies found appeal in the format: it falls between retail and on-demand delivery. Groceries don’t need to reach the buyer within an extremely short timeframe like meals, but they do need to be shipped within a day to retain freshness.

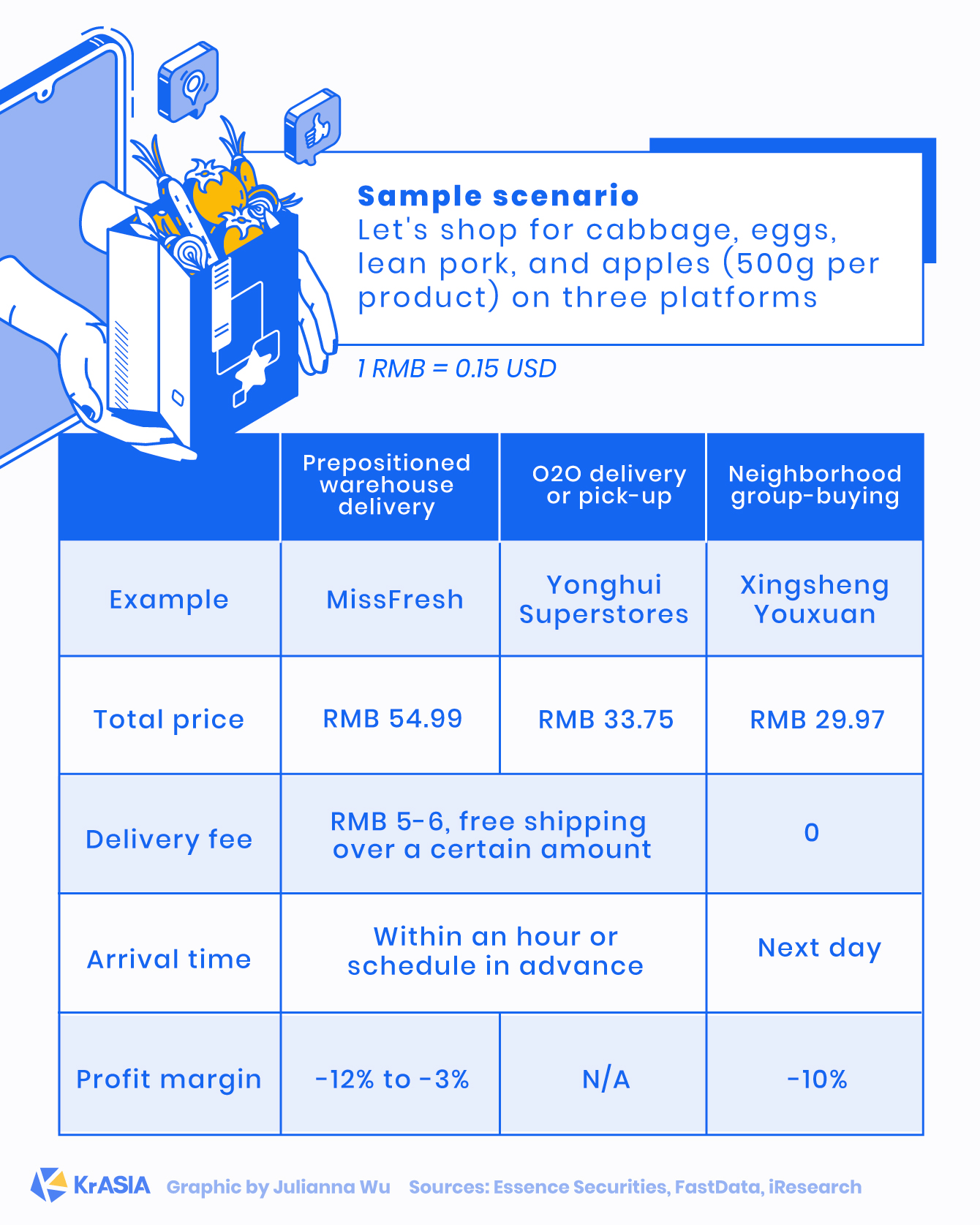

The cost to source, store, and transport groceries, especially fresh produce, runs high. But profit margins per order can be miniscule. The only way to manage this type of service efficiently, it seemed, was to do it at mass scale and amplify profits through volume.

Fast forward to 2021. There are now three relatively mature business models that are tackling this hurdle. Each serves a specific type of consumer.

Prepositioned warehouse

Take Sequoia-backed Dingdong Maicai (DM) as a case study. The company has over 200 stores in Shanghai, covering the entirety of a city that has three times as many people as New York.

Each of these stores functions as a small or medium-sized distribution center that funnels shipments from the central warehouse into densely populated neighborhoods. After a user places an order, goods are shipped from the prepositioned warehouse to these distribution locations. The lead time for delivery is 30 minutes for destinations within a three-kilometer radius from any prepositioned warehouses.

This speed and convenience caters to busy, urban, white-collar elites, who may have little time to shop for themselves but still want to prepare their own home-cooked meals, often on a whim.

Neighborhood group-buying

People in China’s lower-tier cities and counties—about 78% of the country’s population—generally have different shopping habits from residents of urban areas. They are less likely to use tech-based channels, more price-sensitive, and usually plan their meals ahead of time.

One grocery sales and delivery strategy has evolved to fit these habits: neighborhood group-buying. Apps recruit community “leaders” that are trusted by people in their neighborhoods. They may be a grocery shop owner or anyone seeking gig work. These leaders aggregate orders from members of their group one day in advance. The produce is then shipped to a brick-and-mortar location, which could be their own private shops or an unfilled public playground, where the group leader arranges for pick-ups.

READ THIS: China’s tech companies are greengrocers now

Online-to-offline platforms

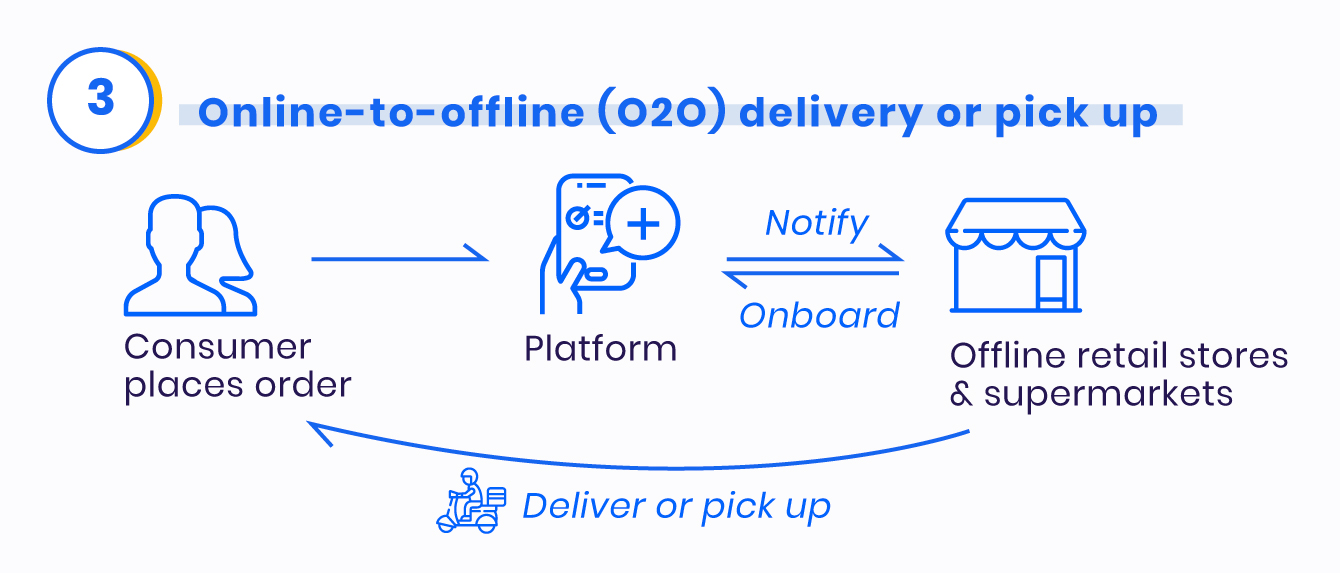

Some businesses blend the two mentioned models for a third approach.

Tencent-back supermarket chain Yonghui Superstores and Alibaba’s “new retail” initiative Hema, for example, have translated foot traffic in their brick-and-mortar stores into traffic for their online platforms. Consumers use these apps to order groceries, which are then delivered or picked up by the buyers.

Netizens can also shop for groceries on JD Daojia, Meituan, and Ele.me. Sharing some similarities with Instacart in the United States and Gojek’s grocery delivery service in Indonesia, these apps host product listings pulled from various supermarkets as well as retail stores, and send shoppers to pick up orders to deliver them to customers.

Hunger Games for capital

A steady flow of cash infusions is necessary to cover the prohibitive cost of this line of business. DM has sealed seven rounds of financing since the company set up its prepositioned warehouses in 2017. MissFresh, meanwhile, raised nearly USD 495 million in a Series F round in July 2020. It was the largest deal in the industry, 36Kr reported.

Frequent and hearty investments reflect the capital market’s optimism toward this business, but it also suggests these companies are operating with massive overhead with questionable paths to profitability.

Prepositioned warehouses involve costly assets like cold chain logistics infrastructure. This model burns more cash than neighborhood group-buying.

Public money in the secondary market is an additional avenue to acquire funds. Both DM and MissFresh are reportedly preparing for initial public offerings in 2021, 36Kr reported, with the latter claimed to have earned a profit last summer.

Meanwhile, neighborhood group-buying has a promising business structure. High-touch social interactions between neighborhood leaders and their group members not only keep orders flowing (even recruiting new users), but also gives platforms a means to introduce daily bargains to consumers—a good way to get rid of static stock. Expenses for shop rent, staff remuneration, as well as delivery are slashed along the way.

This highly replicable business model proved to be a success in provinces like Sichuan and Hubei during pandemic lockdowns across China.

Now, tech giants of all stripes, like Meituan, Pinduoduo, and Didi, have all launched their own neighborhood group-buying apps. The sector is so overheated that the central government warned these companies about falling into cycles of market-wrecking price competitions in late 2020.

There is a drawback. Depending on untrained individuals to act as community leaders and distributors, while paying a sizable portion of revenue, is a risky proposition for neighborhood group-buying startups like Xingsheng Youxuan and Nice Tuan. This is especially true when the business model is easy to duplicate.

Even so, venture capital tycoons offer plenty of cash for this sector’s operators to burn. For instance, Tencent, a conglomerate that doesn’t have its own retail business, has poured investments into various online grocery companies either directly or through affiliates like JD.com and Meituan. One thing is certain: there is no shortage of ways for fresh food from across the country to reach China’s households, no matter where you are.