This story originally appeared in Open Source, our weekly newsletter on emerging technology. To get stories like this in your inbox first, subscribe here.

Taylor Swift is a polymath in her own right. She seamlessly transitions from writing chart-topping songs to captivating global audiences with her live performances. Her foray into directing, marked by a self-penned script, further establishes her breadth of talents.

However, a recent video of Swift, first shared on Chinese microblogging site Weibo, has been raising eyebrows after going viral and making the rounds across the internet.

In this video, Swift graces what appears to be a late-night talk show, eloquently discussing her recent experiences, spanning songs and her recent travels. The interesting bit? She spoke entirely in Mandarin Chinese. From the nuances of her voice to the subtle movements of her face and lips, Swift’s expressions in that video give the illusion of a native Chinese speaker.

The reality is, however, that Swift did not converse in Mandarin Chinese in the original video. Despite being present on the talk show, she communicated in English, and the video circulated on the internet is a version that has been modified using artificial intelligence.

Putting words into someone’s mouth

This manipulation stems from advanced speech synthesis technology, employing deep learning techniques. By analyzing for and extracting audible characteristics from voices (audio data), this technology can clone and replicate them, generating words, phrases, and even complete sentences.

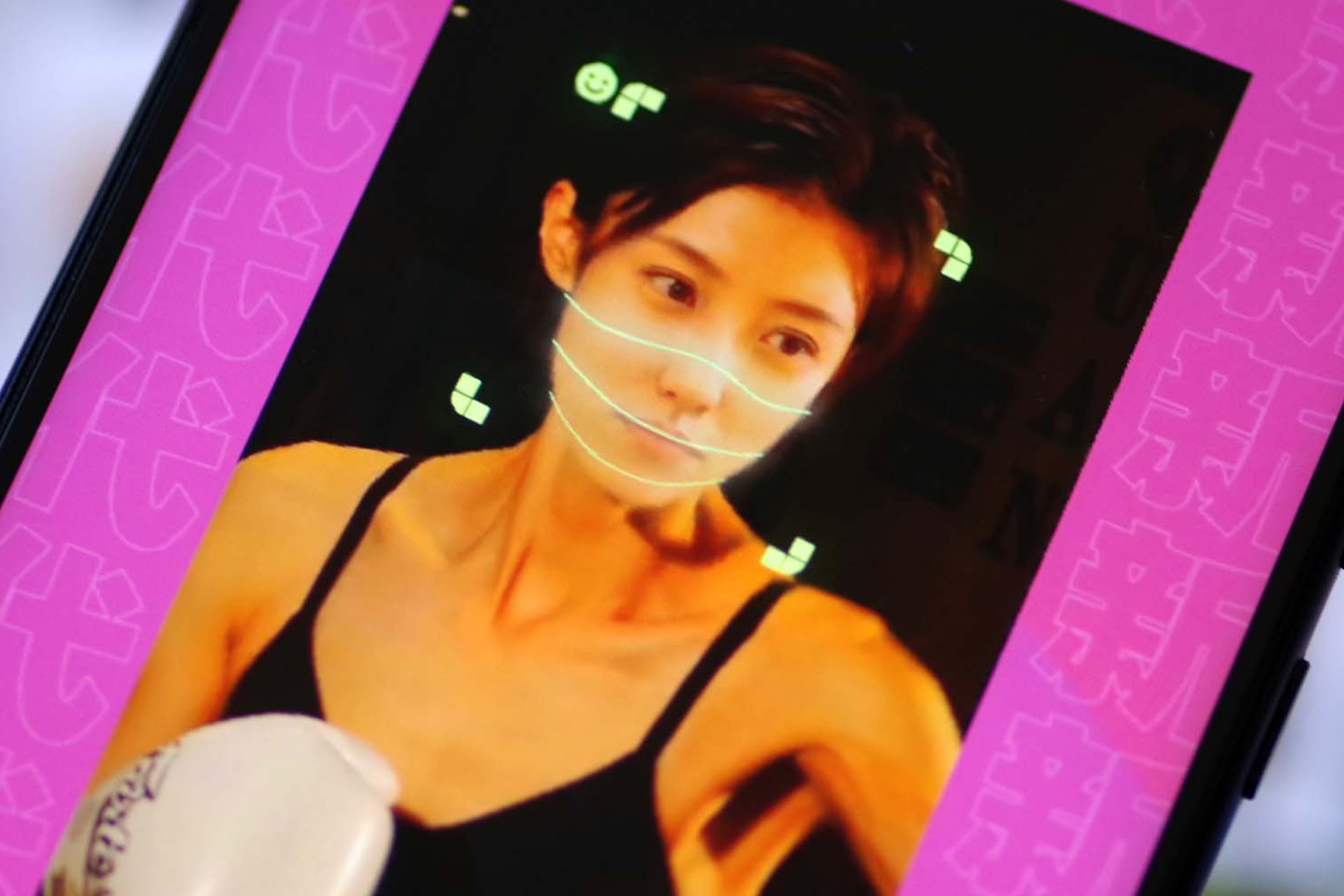

The deepfake video of Swift was generated using a tool developed by Chinese startup HeyGen. The company first launched as Surreal, later changing its name to Movio before rebranding to HeyGen.

According to HeyGen’s website, its video translation tool boasts the ability to translate footage into 28 languages, creating a “natural voice clone” synchronized with authentic lip movements. The website is embedded with a demo of the tool’s capabilities, showcasing American YouTuber Marques Brownlee and Elon Musk speaking Spanish and French respectively—languages foreign to their usual discourse.

Public reactions to the use of this technology have been varied, with concerns primarily revolving around its potential for abuse. As these tools become more user-friendly and their outputs increasingly realistic, they may be used for nefarious activities, such as scams and frauds.

Notably, AI-driven fraud has been on the rise globally, prompting countries like China to enact new laws governing generative AI use. Beijing has mandated companies to obtain consent from individuals whose likenesses are manipulated, with deepfakes required to be labeled as such online. Deepfakes are also prohibited from use in activities deemed harmful to national security or the economy.

However, the efficacy of such policies has been a subject of skepticism, primarily due to their vague nature and challenges in enforcement. For example, HeyGen’s relocation from Shenzhen to Los Angeles has effectively exempted it from China’s deepfake regulations.

Risks aside, advanced speech synthesis technology, particularly cross-lingual models (like Microsoft’s VALL-E X), actually offer potential to explore a variety of new and exciting applications. Filmmakers could leverage this technology to dub their films, enhancing the naturalness of dubbed audio. Livestreamers could engage in real-time communication with their audiences using their own voices, even in languages they don’t speak fluently. The possibilities are (nearly) boundless.

Yet, one of the most intriguing applications may perhaps lie in music.

Composing the dream track (if it exists)

Dream Track is an experimental project designed by YouTube and Google DeepMind. Its goal is straightforward: using AI to try and change the way music is produced.

By structuring an idea into a text-based prompt and selecting an artist who’s participating in the project, Dream Track users can automatically generate an original song snippet of up to 30 seconds in length featuring the AI-generated voice of the selected artist.

Nine artists have hitherto agreed to take part in the Dream Track project, including Alec Benjamin, Charlie Puth, Charli XCX, Demi Lovato, John Legend, Papoose, Sia, T-Pain, and Troye Sivan.

Projects like Dream Track could eventually usher in a paradigm shift in music production. By synthesizing vocal clones, artists will no longer need to work solo. Instead, they can “lend” their voices to fans, unlocking more collaborative ways of creating music. In this scenario, fans become actively engaged, and artists find themselves doing less of the legwork—it appears to be a win-win situation.

But before embracing this seemingly revolutionary prospect, it’s critical to consider this: when the artist’s voice becomes a pliable instrument in the hands of the audience, does it erode the authenticity and integrity of the creative process? Does it reduce the artist to a mere conduit for the whims of the masses?

These questions compel us to contemplate whether the pursuit of a creative renaissance should come at the cost of commodifying artistic expression—a dilemma that Singaporean mandopop artist Stefanie Sun is likely well acquainted with.