Before COVID-19 largely shut borders in Southeast Asia, Singapore resident Kin Wong would take weekly drives to Malaysia in his BMW M3.

The 40-year-old avid motorist is thinking about giving up the gas-thirsty convertible for a more environment-friendly electric vehicle. But he is hesitating, and not because of the BMW engine’s satisfying rumble.

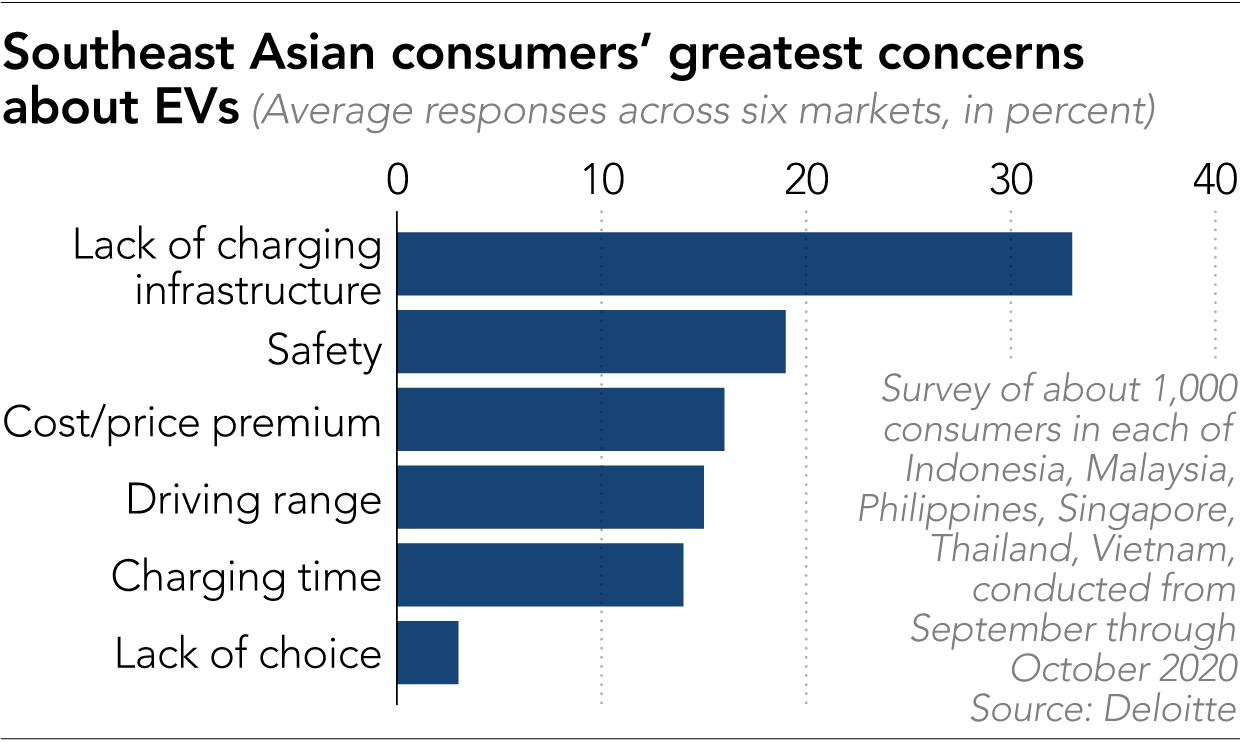

“The concern is infrastructure—the charging availability, like how many charging points are available,” Wong said. He is also unconvinced that government EV incentives sufficiently offset the cars’ relatively high prices.

As the world prepares to gather for the United Nations’ COP26 climate conference in early November, green mobility is in focus. Road transport accounts for 10% of global emissions, the conference organizers note, with output increasing “faster than any other sector.” Alok Sharma, the COP26 president, has said the world needs to double the pace of EV take-up over already “optimistic” estimates that they will account for over half of new car sales by 2040.

This is a global challenge to be sure, but cleaning up Southeast Asian roads will be part of the battle. Overall, about 3.5 million passenger or commercial vehicles and 4 million motorcycles or scooters were sold annually before the pandemic, data from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Automotive Federation shows. The region is also expected to generate 140 million new consumers by 2030, with the high and upper-middle-income ranks doubling to 57 million, according to the World Economic Forum.

Drawn by these potential customers and countries’ big ambitions to promote EVs, global companies from China’s Great Wall Motor to South Korea’s Hyundai Motor Group and LG Energy Solution have shown an appetite for investing in local vehicle or battery production. They see an opportunity to crack strongholds of Japanese automakers, which continue to push hybrids and have expressed unease about a rapid phase-out of gasoline-powered vehicles.

Maybank Kim Eng projects EVs will outsell internal combustion-powered cars in ASEAN by 2035. But recent surveys suggest consumer sentiment toward pure electric cars is still lukewarm at best. Industry watchers also say EV adoption across the bloc of over 600 million people could be slowed by a lack of clear strategies and inter-governmental coordination. ASEAN’s vision for furthering regional cooperation—the Socio-Cultural Community Blueprint 2025—makes no explicit reference to cleaner transport.

To get more EVs on their roads, Southeast Asian governments face the challenge of sharpening policies to spur production and adoption in the coming years.

Vivek Vaidya, associate partner at research consultancy Frost & Sullivan, told Nikkei Asia that ASEAN countries are taking piecemeal approaches. “Every country has their own take on it, every country has their own considerations, and therefore they have their own strategies,” he said. “So right now, we don’t see any unified or coherent response” for EV promotion among ASEAN members.

Yossapong Laoonual, a former president of the Electric Vehicle Association of Thailand (EVAT) who now heads the Mobility & Vehicle Technology Research Center at King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi in Bangkok, said consumers need reassurance that they can charge their cars even if they cross national borders—as easily as they can connect their smartphones to local cellular networks.

Yossapong also suggested tax systems may need to be restructured to prod companies to shift to EVs faster, forcing those that make hybrids and plug-in hybrids to pay more. “At the moment in Thailand, hybrids and plug-in hybrids with carbon dioxide emissions less than 100 grams per kilometer are treated in the same category as electric vehicles—as low-emission cars,” Yossapong said. “It is meaningful to make it more attractive for the car industry to produce zero-emission vehicles such as battery electric vehicles.”

Despite Wong’s reservations about trading in his BMW, Singapore appears committed to EVs. Maybank analyst Liaw Thong Jung called the city-state “the most forward-looking and the fastest to embrace e-mobility” in ASEAN.

As of Aug. 31, just 1,855 out of the 641,977 passenger cars in Singapore were fully electric, according to the Land Transport Authority. Still, last year, the city-state said it intends to entirely phase out vehicles with internal combustion engines by 2040.

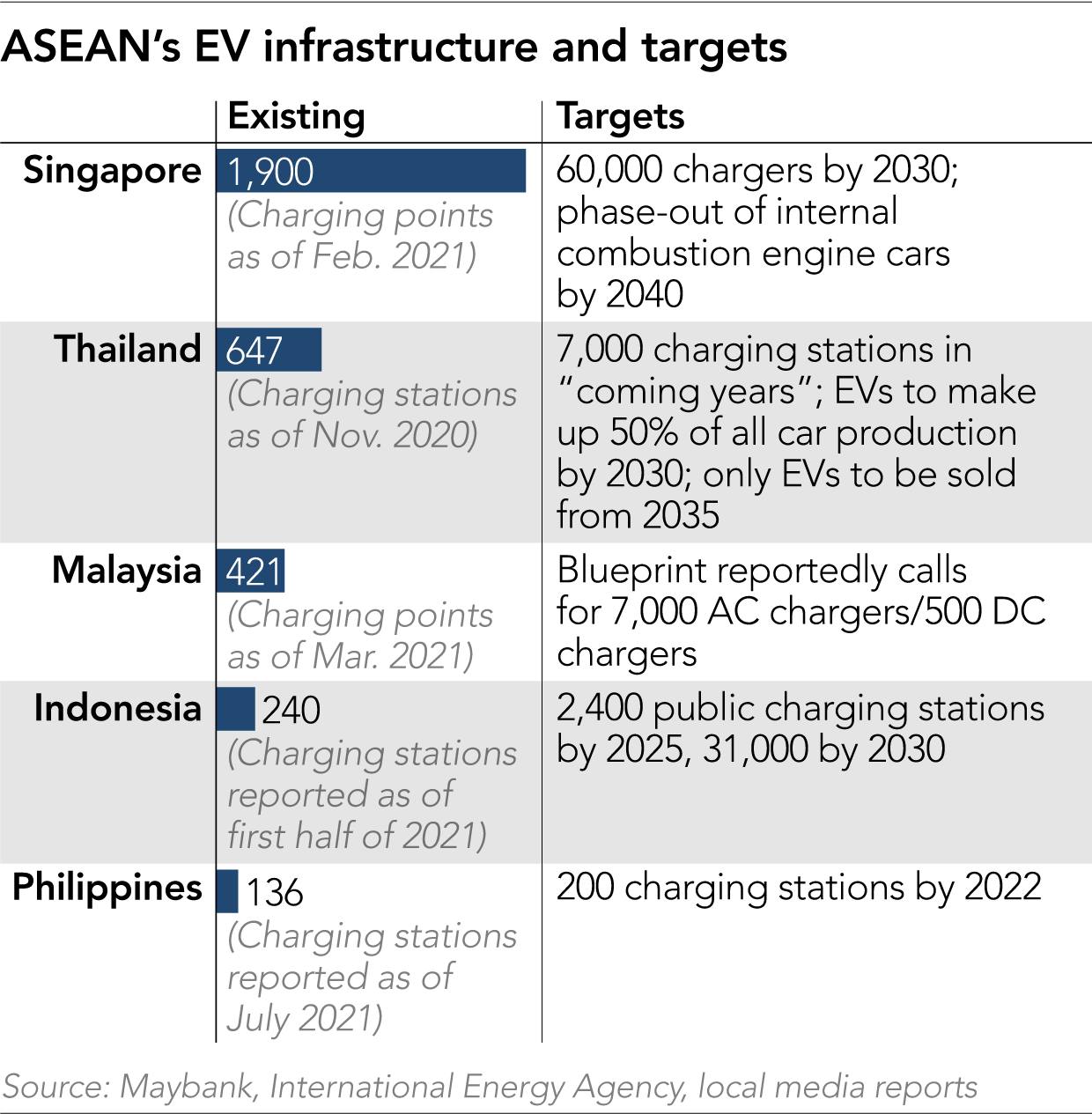

Regardless of powertrain, Singapore is known as the world’s most expensive place to own a car, with layers of taxes meant to control vehicle numbers. But to spark the EV transition, an early adoption incentive available through 2023 offers buyers up to SGD 20,000 (USD 14,800) worth of relief from government registration fees. And to address charging concerns, the authorities aim to increase the number of points from around 2,000 now to 60,000 at public and private parking lots by 2030.

Singapore has also welcomed foreign investment in EV development. Hyundai last year began building a research and development center in the city that will include small-scale capacity for manufacturing electric cars. The South Korean automaker plans to let customers watch their cars being built before taking the finished product for a spin.

Maybank’s Liaw also gives Indonesia and Thailand high marks for “clear-cut EV policies, in terms of phasing out internal combustion engine vehicles, setting EV production or sales targets, providing subsidies to encourage EV adoption and accelerating the charging infrastructure build-up.”

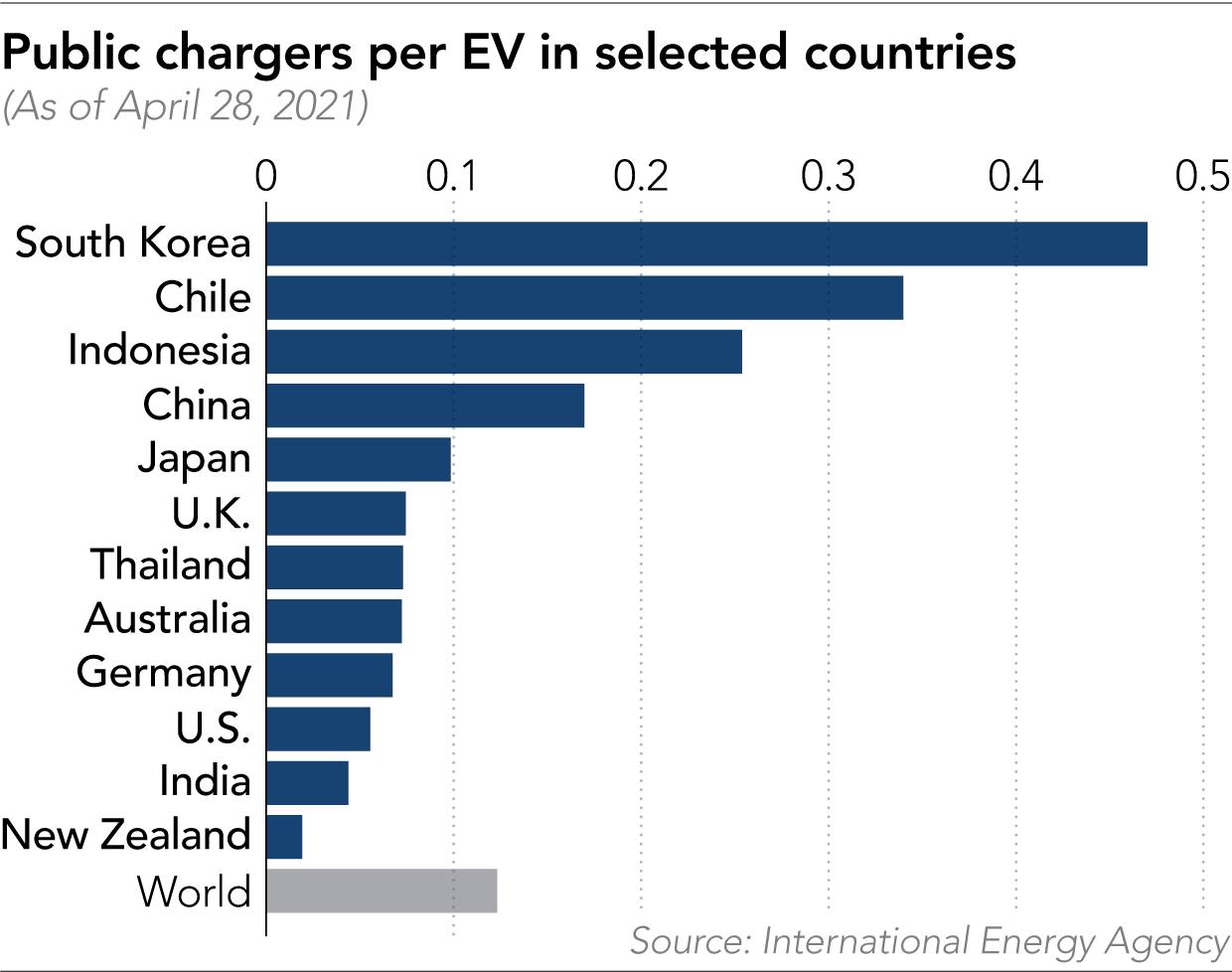

Indonesia—which has one of the world’s higher ratios of chargers to EVs according to the International Energy Agency—has set a target of 2,400 charging stations and 10,000 battery swap stations by 2025. By 2030, it aims to have over 31,000 charging stations, as the government projects more than 2 million electric cars and 13 million electric motorbikes will hit the streets by that year. The country also hopes to leverage its nickel resources to become a major battery production base.

Thailand—the region’s largest auto production center—plans to lift output of purely electric vehicles to 50% of all car manufacturing by 2030, and to only allow EVs to be sold from 2035. EVs made up well below 1% of total registered vehicles last year.

On the other hand, a Maybank Investment Bank Research report named the Philippines and Malaysia as laggards with “ambiguous” EV policies.

The Philippines “does not have a clear, defined EV roadmap yet,” Maybank said. A bill that cleared the Senate this year would require private and public buildings to have dedicated parking slots with charging stations. The Department of Energy also published a circular on protocols for charging stations. But there were fewer than 140 as of July, according to local media, and proponents say the country still lacks an overarching EV law to encourage adoption.

Malaysia, for its part, emphasizes sustainable transportation in its National Automotive Policy. But the latest edition for 2020—written back when Mahathir Mohamad was still prime minister—sticks to broad goals like developing an “EV charging protocol” and “energy management system” for the “EV ecosystem.”

Malaysia reportedly has a Low Carbon Mobility Blueprint that proposes a push for 7,000 AC chargers and 500 faster DC chargers, while a far loftier figure of 125,000 chargers by 2030 has also been reported. The blueprint calls for tax breaks for hybrids and fully battery-powered EVs as well. But Liaw said such incentives fail “to drive home the aspiration to accelerate EV adoption.”

“The policy needs to re-focus on battery EVs and less on plug-in hybrid EVs,” he wrote. “Until then, Malaysia is unlikely to inspire auto original equipment manufacturers to bring in their battery EV pipelines.”

Therein lies a key battle line—hybrids versus pure EVs—and an awkward issue for some governments and Japanese companies that have played a prominent role in building the ASEAN auto industry.

Consider Thailand, where Japanese cars command a roughly 90% market share, decades after players like Toyota Motor and Honda Motor established local plants.

The government’s ambition to create an EV production hub has attracted newcomers like Great Wall, which opened its first local plant in June. The Chinese company expects to begin making EVs there as early as 2023, according to local reports.

Foxconn, the giant Taiwanese contract manufacturer known for supplying Apple, and Thai state energy group PTT last week agreed on setting up a joint venture to develop an EV production platform, vowing to invest up to USD 2 billion.

Japanese carmakers are also expanding their EV lineups, but without the zeal of the new competitors or Western rivals. Toyota, which pioneered hybrids combining electric motors with gasoline engines, has been outspoken against drastic policies to force a shift to pure EVs.

Akio Toyoda, the company’s president and head of the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association, warned earlier this month that “excessive” regulation of gas-powered vehicles in its home market would severely hurt employment. Likewise in Thailand, the auto division of the Japanese Chamber of Commerce in Bangkok previously urged the Thai government to opt for a more phased-in approach to EVs.

But Yossapong, the former EVAT president, argued that “now is the take-off period that you cannot miss, and everyone is trying to be the first mover of the EV market.” At this rate, “Japanese carmakers may not be able to catch up with other automakers, which are [focusing on] new technologies,” he said, adding that Thai parts suppliers that have worked with Japanese clients are likely to land contracts from the likes of Great Wall and Foxconn.

Still, he conceded that the market shift could take over a decade. And the question of demand persists: For now, hybrids are the green cars Southeast Asians actually want.

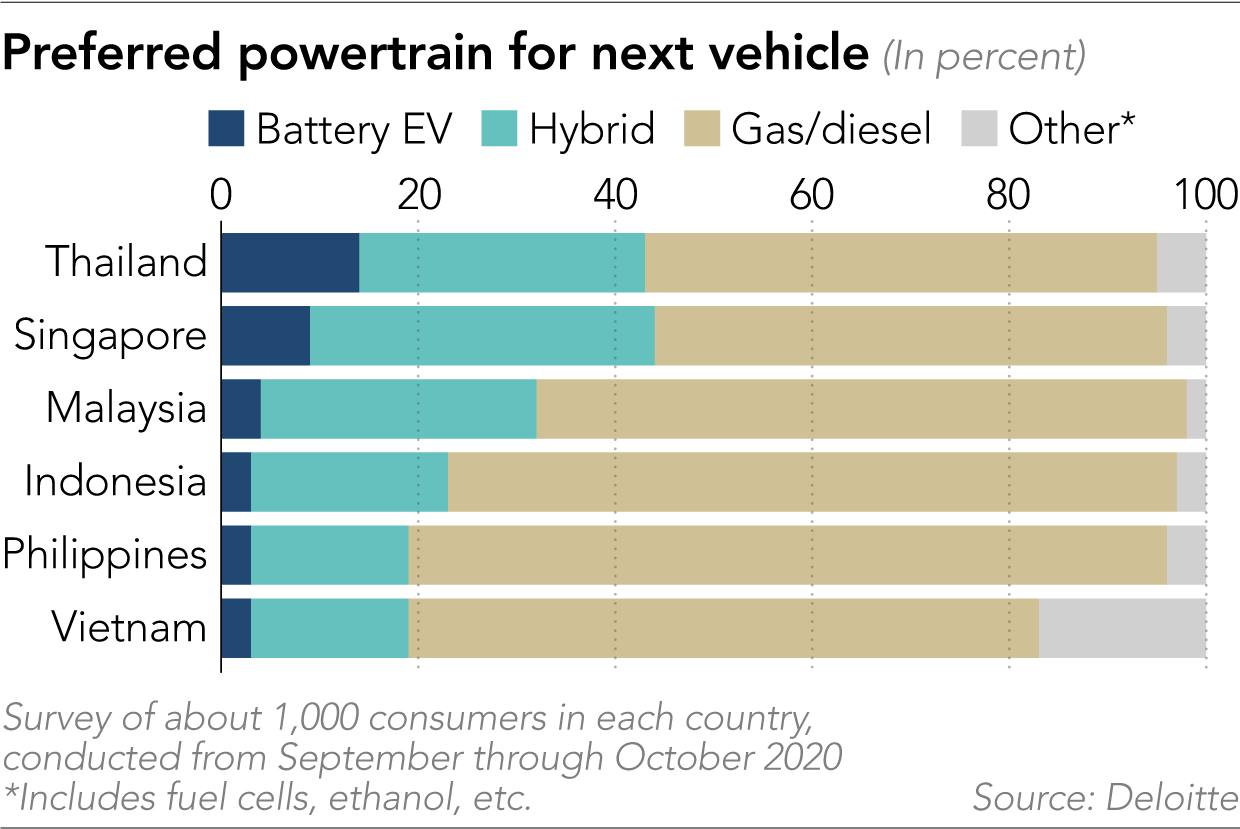

A survey by Deloitte conducted late last year showed few consumers in key ASEAN markets were ready to take the EV plunge when buying their next vehicle, led by 14% in Thailand and 9% in Singapore. Most drivers were still eyeing gas or diesel vehicles, with hybrids the preferred cleaner option.

Thirty-three percent of respondents cited the lack of EV charging infrastructure as the main sticking point. Price was flagged by 16%—though those concerns could soon be mitigated. Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts that by 2023, the cost of the average battery pack will fall to USD 101 per kilowatt-hour—roughly the “price point that automakers should be able to produce and sell mass market EVs at the same price (and with the same margin) as comparable internal combustion vehicles in some markets.”

There are larger issues to consider, too, such as how countries generate the juice needed to make EVs truly emissions-free. The IEA says “Southeast Asia is one of the few regions of the world where coal-fired generation has been expanding, with close to 20 gigawatts of new coal-fired generating capacity under construction” as of last December.

But for policymakers, addressing the charger issue is an obvious first step.

“Apart from improvements to battery capacities and charging technology, a comprehensive and widely accessible charging network is essential to reduce range anxiety,” said Andrey Berdichevskiy, leader of Deloitte’s Future of Mobility Solution Centre in Singapore.

Dale Hardcastle, partner at US consultancy Bain and Company, stressed the need for concrete action.

“Most of the focus has been lip-service versus serious action to drive the mobility transition, with governments waiting to see [what happens],” Hardcastle said of the ASEAN market. “So the region has been caught in a chicken and egg situation—lots of future talks but little short-term action to catalyze the shift.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.