Like most air carriers, Singapore Airlines has suffered during the coronavirus pandemic. But since December, passengers flying the airline from Jakarta or Kuala Lumpur have received a lift from a digital health tool developed by a small startup owned by Temasek—Singapore’s state-owned global investment giant.

Singapore Airlines is one of a number of carriers using travel pass software from Affinidi, one of Temasek’s little-known startups. The software verifies the authenticity of flyers’ COVID-19 test results. One of its main features is that it supports different health passports, making it simple for airlines to screen passengers.

Temasek has been a prolific investor in tech companies. But what differentiates Affinidi from Temasek’s other holdings is that it is homegrown, established by the state-owned investor as part of a move to fund ventures at the earliest possible stage.

Temasek is not just backing promising young companies, it is also making them.

“As an investor, we have full flexibility to either invest in existing solutions or create new ones, depending on the opportunities we have identified,” Chia Song Hwee, deputy chief executive of Temasek International, told Nikkei Asia.

Temasek International is the commercial arm of Temasek Holdings, created to undertake investments so that its parent can focus on stewarding Singapore’s reserves. This month Temasek International is expected to reveal the performance of its portfolio over the 12 months to March.

State-backed investors typically follow the example of venture capitalists or private equity players, backing promising companies with the aim of collecting returns down the road. Temasek, for example, has backed companies such as Southeast Asia unicorn and superapp provider Grab, and China e-commerce giants Alibaba Group and Tencent.

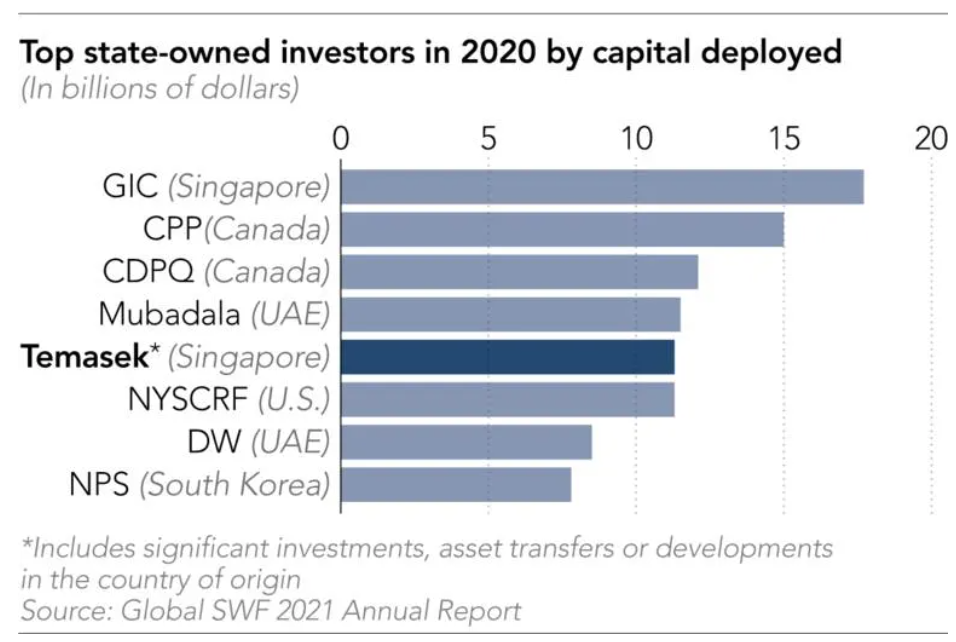

According to data platform Global SWF, Temasek was the top tech backer internationally last year among state-owned investors at USD 2.3 billion—a reflection of the company’s interest in the sector.

Starting companies from scratch, on the other hand, is rarer, as it means devoting investment capital to take on the risks of forming an enterprise from the ground up.

“It would be a long-term endeavor,” Chia said of Temasek’s strategy. “Like all areas of significant change and progress, these have a gestation period that could span years and, probably, come with occasional twists and turns along the way,” he added—an acknowledgment that the path ahead may not be so straightforward.

Besides Affinidi, Temasek has set up Istari, a cybersecurity company. Established in 2019, Istari helps businesses beef up cybersecurity defenses, mitigating the risks posed by sophisticated hackers.

The company has dedicated units covering areas like cryptographic technology, consulting, and incident response, in addition to monitoring the activities and trends of hackers.

Tech startups like Affinidi and Istari focus on growth in developing areas like blockchain and cybersecurity, says Stephen Forshaw, Temasek’s head of public affairs.

Forshaw said Temasek does not earmark massive amounts of capital to start these enterprises and will release capital in stages to support expansion over time. “You don’t write one big check,” he said.

Temasek has not revealed how much it is putting into startups.

Singapore has been keen to bill itself as an Asian technology hub, with the government announcing a special work visa in November last year to attract startup founders, leaders, and technical experts with experience in established or fast-growing tech companies. But Forshaw says it is coincidence that Temasek’s investment strategy squares with the goals of the Singapore government. The investor is simply acting on where it sees opportunities.

Temasek’s model is not a case of the company hiring entrepreneurs with ready-formed ideas. Rather, Forshaw said, internal staff are suggesting opportunities, coming up with plans, and seeking approval and funding.

“Part of the job of those people is to get the business up and running and then bring in a professional management team,” he explained.

Forshaw said this was what happened in Affinidi’s case, with Temasek organizing a handful of its own staff to kick-start the company with existing capital before recruiting others to round out the startup.

A high-profile hire for Temasek was Glenn Gore, who moved to Affinidi as CEO after a stint as chief architect at Amazon Web Services in Seattle—the cloud computing subsidiary of the e-commerce group.

Gore told Nikkei that the startup’s goal was to build and refine information service applications that other businesses will find uses for. He said Affinidi is engaging potential partners across Southeast Asia, India, and China. The company now employs about 50 people.

“To help us grow, we continue to look for and hire quality and diverse talent based on our business needs,” Gore said, adding that he expects his teams to expand, focusing on applying Affinidi’s tech to other companies.

Temasek’s creation of its own startups is “a big shift,” said Abhineet Kaul, head of Asia-Pacific operations for public sector and government consulting at Frost and Sullivan.

“There are significant risks, not only financially, but reputation-related for Temasek,” he told Nikkei. “The business model of these startups is also not tested for investment by a state investor,” Kaul said of Temasek’s Affinidi venture.

“The core objective of Temasek should be to increase wealth for Singaporeans through relatively low-risk strategy,” Kaul said, noting how the investment company is accountable to the Singapore government as its sole equity shareholder.

Temasek’s Chia acknowledged that the approach “may have higher risks” but would “bring about opportunities to grow alongside the companies.”

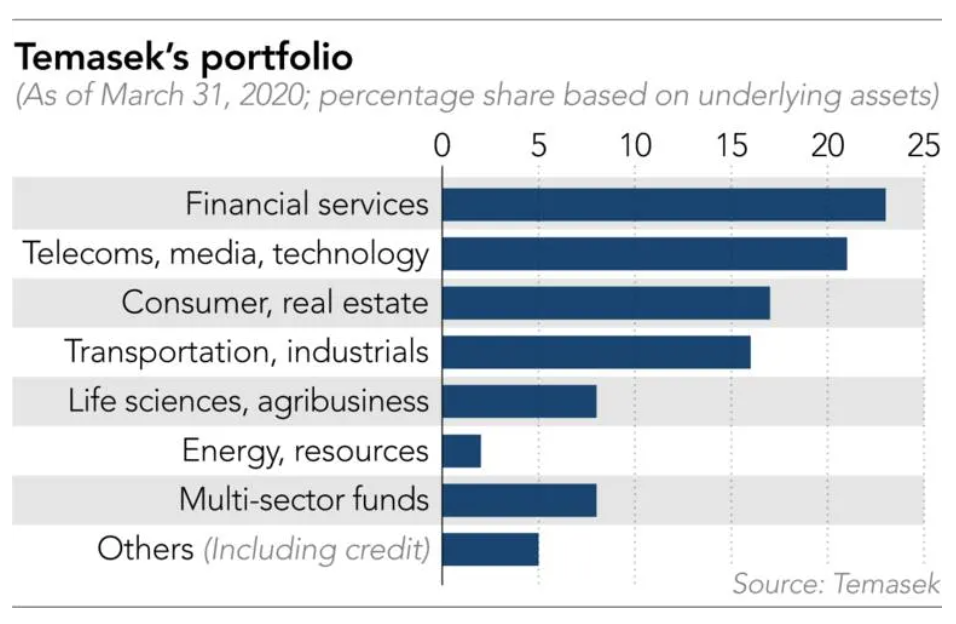

Temasek’s investments are still small relative to its portfolio currently valued at SGD 306 billion (USD 220 billion). But they show that Temasek is raising the prospects of its long-term future by seeding companies it hopes can grow to be industry giants.

The company’s diversified approach also comes amid struggles for decent returns. In the fiscal year ended March 31, 2020, its return was minus 2.28%—down from 1.49% in 2019 and the worst since 2016. Net portfolio value for the period declined about 2% to SGD 306 billion.

Temasek cautioned last year that the global market outlook remained volatile and uncertain, with COVID posing a risk to recovery. Over the fiscal year to the end of March 2020, Temasek invested SGD 32 billion and divested SGD 26 billion.

The company’s portfolio has its largest weighting in Asia, amounting to 66% of its exposure by underlying assets. China at 29% and Singapore at 24% are the top two countries by concentration.

Temasek’s leadership transition plans also suggest a renewed focus on its commercial opportunities.

In February, the company said Ho Ching would retire in October after 16 years as CEO of Temasek Holdings, the parent group. Her successor will be Dilhan Pillay Sandrasegara, CEO of Temasek International, who will also retain that role. Sandrasegara previously led the Enterprise Development Group, a unit set up in 2014 to pursue commercial opportunities.

Temasek has also entered into joint ventures to pursue commercial opportunities. Last year, it announced a partnership with the investment arm of German life sciences company Bayer to establish a business in vertical farming.

Lawrence Loh, director of the Center for Governance, Institutions and Organizations at the National University of Singapore Business School, said Temasek’s self-created startups place it “at the cusp of a new trend.”

“By creating startups rather than investing in them, Temasek can move to directly generating returns rather than from indirectly receiving returns,” Loh told Nikkei. “The approach will augment the traditional equity portfolio with a new concept—an in-house ‘super-incubator.'”

He said the state investor’s move would potentially make it more of a “sovereign wealth enterprise”—transforming its activities from merely holding a financial portfolio to functioning more like a business conglomerate. The challenge, he said, will be to internally build up the capabilities of the new companies.

Chia highlighted that the Enterprise Development Group already sets its sights on endeavors that may have lengthier gestation periods and potentially bear greater risks.

“We may therefore be better placed to address some of these challenges and gaps we see because of our long-term view and orientation—our ability to provide capital over longer horizons and a more patient stance towards a path to profitability and commercial returns for these circumstances.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.