The COVID-19 pandemic has not only exposed but enlarged the cracks within our fragile food systems.

In Asia, we witness nationwide lockdowns and border restrictions in ASEAN. There are heightening fears of food shortages, food dumping in protest against restrictions on cargo movement, and the virus disproportionately impacting malnourished children in Indonesia.

Food security, health, and environmental challenges are all intertwined. Experts have highlighted the need to rethink our global food systems to be more sustainable and resilient. While food geopolitics and global supply chains require action from governments and multinationals, other stakeholders like farmers, startups, and consumers have an integral part to play too.

In a climate characterized by frequent and rapid change, we have the opportunity to critically re-evaluate our choices. In the first of our Reboot 2020 Food & Agriculture pieces, we will broadly explore how we can enable a more sustainable and resilient food system in terms of better supply, quality, and diversity, from farm to table.

Strengthen and decentralize food supply: Enable smallholder farmers and strengthen local food production.

In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, food supply and security concerns have accelerated the need to localize food production, which will decentralize the risk in global food supply chains.

Southeast Asia is home to over 70 million smallholder farmers. These regional smallholder farmers do not enjoy the same access to technology as their counterparts in more advanced economies and are often still applying more traditional agriculture practices. We believe that the adoption of digital technologies can move the needle in their favor.

Digital technologies can bridge geographical differences and overcome information asymmetry, by enabling access to finance, marketplaces, and knowledge. Over time, this translates to better agricultural productivity and yield for smallholder farmers. We observe that understanding local cultural and behavioral nuances is key to technology adoption. Grow Asia interviewed smallholder farmers who indicated that they prefer using social media—WhatsApp and Facebook—to support their farming operations, instead of industry-specific apps. Farmers prefer tools that are essentially social, where they can access tried and tested information shared by peers they trust. In our upcoming pieces, we will explore the growing opportunities for technologies and startups to enable rural smallholder farmers, in greater detail.

The rise of urban farming means that food production need not be totally confined to rural areas. Urban farming has been touted to be an environmentally friendly mode of food production that uses less land, water, and energy. Yet, it is still in its early stages and challenges still abound, especially in relation to scalable business models for urban farms. In addition, vertical farms may not be commercially viable because the initial setup is expensive and the kind of greens demanded by the local markets may be low-value.

That having been said, we see great progress being made in Southeast Asia. Singapore is currently the front-runner in the vertical farming domain, with more than 30 vertical farms in Singapore in 2018 and prominent startups such as Sky Greens and ComCrop leading the charge. Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand have all witnessed growing movements and support from their respective governments. Looking ahead, with continued technological support, urban farming could serve as a valuable complement to the food system to diversify and increase food supply.

More diversity in our diets: Changing social perceptions and raising awareness of ‘forgotten’ and ‘unloved’ crops.

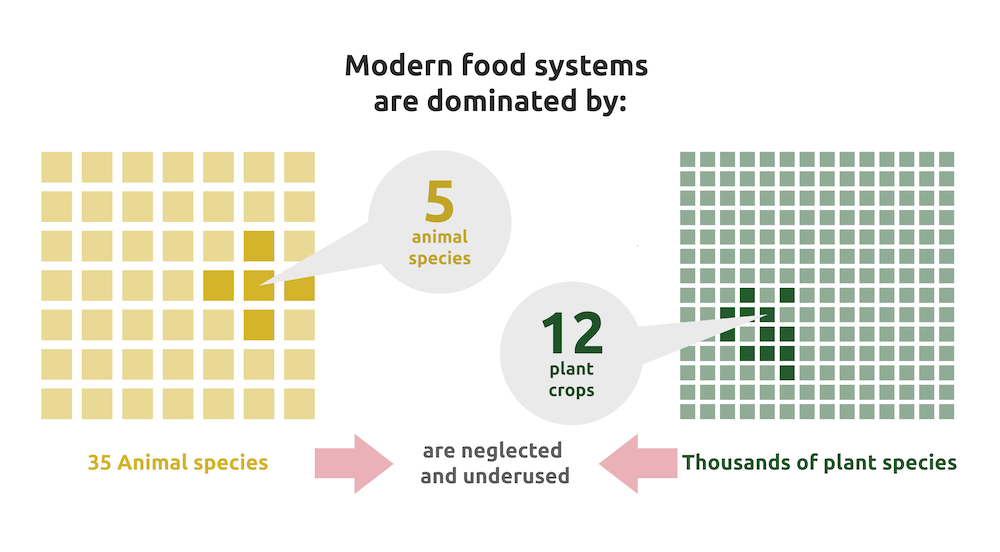

The suggested improvements to food supply should not just be applied to our current major food species alone. We should rethink and diversify our diets, by raising awareness and changing social perceptions of ‘forgotten’ or ‘unloved’ crops. With the plethora of options in our supermarkets, we may be surprised or even alarmed to learn that our modern food system is dominated by just five animal species and twelve crops. Even though there are over 391,000 plant species, only three crop species —wheat, corn, and rice— provide more than 50% of the world’s calories from plants.

Diseases and climate change can disrupt this delicate balance by wiping out large swathes of monocultures that underpin our crop supply and source of animal feed.

Diversifying diets will achieve the dual outcomes of boosting food security (by spreading risk) and achieving better nutrition. Additionally, forgotten crops are among the most climate-resilient and nutritious. In order for these ‘forgotten’ or ‘unloved’ crops to be re-introduced into our diets, awareness and social perceptions have to change.

Some crops have been farmed for centuries but are virtually unknown outside the regions to which they are indigenous—such as Moringa trees, bambara groundnuts and kedondong berries that are grown in Malaysia. In other countries, there are perceptions of local crops as “old or poor people’s food” or as inferior “women’s crops.” Clearly, a repositioning exercise is required to showcase these hidden gems and bring their myriad merits to the fore. As demand for these alternative crops grows, farmers will be incentivized to cultivate them.

Better food quality: Strengthening human nutrition

Beyond growing more food, the pandemic has sharpened the global focus on nutrition. The pandemic has shown that our health systems are susceptible to unforeseen changes. Hence, we see more consumers taking a proactive approach to their own nutrition.

Yet, it is worth noting that regardless of the improvements in nutritional content, taste, and convenience will remain key to driving adoption. How can we increase the nutritional value of our foods without compromising changes in taste and lifestyle? Food fortification and personalized nutrition have emerged as promising trends.

Staple food fortification can alleviate malnutrition by packing more nutrients into our staples, without significantly changing their look, taste, or cooking method. Vitamins and minerals are blended with broken-down rice, and safely “locked in” when new kernels are produced through hot extrusion. The pioneer of this unique technology for fortified rice, Royal DSM’s Nutritional Product, is now using the same technology for another popular Asian staple—lentils. Lentils provide an excellent source of proteins and also address the global demand for plant-based diets in which pulses are a large component.

In addition, more consumers are embracing preventative health maintenance and enhancement, seeing supplements as a “must-have” instead of a “good-to-have.” For dietary supplements, personalized nutrition could become “the future,” by providing more targeted nutrition and replacing tens of daily supplements, and offering greater effectiveness and more convenience. Although still in early stages, these solutions have demonstrated great potential to evolve and advance by overcoming challenges in product formulation and consumer feedback.

Conclusion

By shining a light on various vulnerabilities in global food systems, COVID-19 has created the opportunity for us to rethink the way things have always been done, and strive to become more sustainable and resilient. How might we enable our food systems to have better supply, quality, and diversity, from farm to table?

As we work towards improving our food systems, it is key to acknowledge the interplay of food security, health and sustainability issues. Often, health and climate events disproportionately impact vulnerable communities in less developed countries. Yet, these communities form the bedrock of our global food supply. How can we better equip and uplift these communities?

We believe we will see Food and AgriTech grow tremendously in the near future, particularly in the realm of smallholder farming, urban farming, and human nutrition. Separately, there is an opportunity for us to fundamentally recognize that our increasingly uniform diet presents both supply and nutritional issues, and a diversified diet is the way forward. When it comes to food, people are conditioned by social perceptions and culture. When implementing these changes and technologies, it is important to consider societal, cultural and behavioral nuances as well.

To read similar stories, please hop on to Oasis, the brainchild of KrASIA.

The Padang & Co story started with Singapore’s first major public hackathon, UP Singapore, in 2012. Since then, this organization has been bringing people and organizations together to solve problems, develop ideas, and new solutions. Their aim is to create the environment for creativity and innovation to emerge and flourish. Get in touch with Christina Ho at [email protected] to share your thoughts.

Disclaimer: This article was written by Christina Ho, Program Manager at Padang & Co. All content is written by and reflects the personal perspective of the writer.