The live-streaming industry, enabling real-time interactions between fans and content creators, has taken off around the world—especially in China, where there are several established live-streaming platforms like YY, Inke, Momo, and Douyu.

Across Southeast Asia, there are only a couple of notable live-streaming platforms, such as BIGO Live, Thai platform Kitty Live, and the Singaporean startup BeLive. The big players, like BIGO and Kitty, tend to be backed or owned by Chinese firms.

The live streaming genre where people broadcast their daily life is also known as in-real-life (IRL). It’s one of the most popular genres because it invites everyone to participate and can therefore potentially reach mass scale.

Although IRL live streaming became a hot topic in Southeast Asia in its early days around 2015, it soon became obvious that the format has some issues. The revenue model wasn’t sustainable for some creators, and IRL live streaming earned a bad reputation for its adult content.

Today in Southeast Asia, live streaming is diversifying. Video game live streaming and live streaming for social shopping are starting to emerge as niches for specific audiences. Its also being challenged by new formats, such as short-video apps. Meanwhile, IRL live streaming is trying to find its place after the initial hype has cooled off.

Live streaming’s early days in the region

When live streaming emerged in Southeast Asia in 2015, apps such as BIGO Live quickly moved up the charts in countries like Indonesia and Thailand.

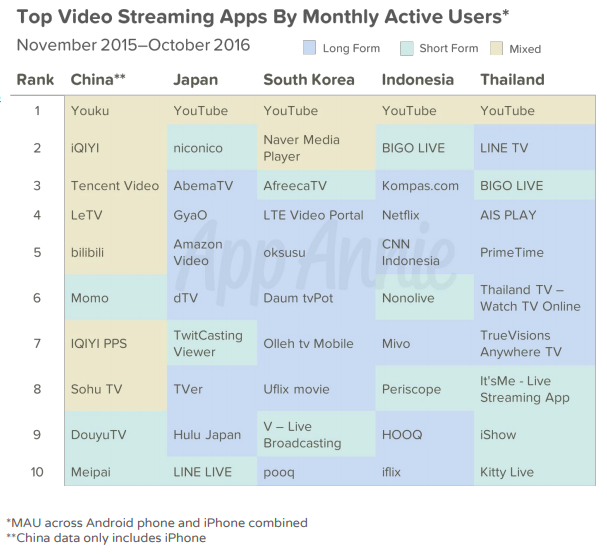

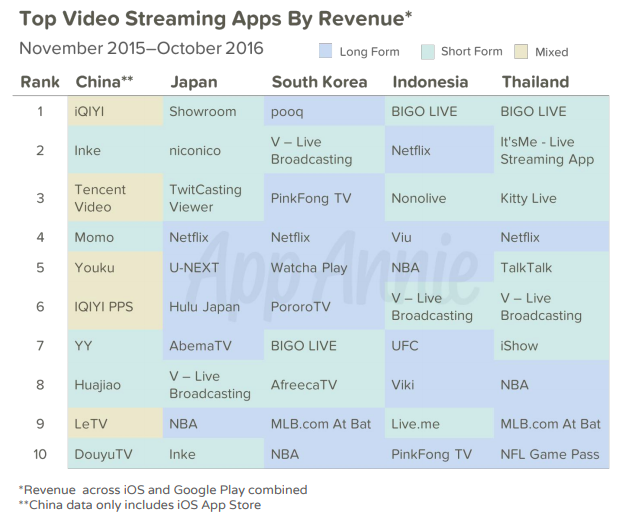

According to App Annie’s report on video streaming in Asia, BIGO Live surpassed all other platforms in its category in Indonesia and in Thailand, such as the US-made Periscope, in terms of monthly active users. It also lead in its category in terms of in-app revenue.

Live streaming platforms appeared to be doing well in the region, but that rosy period did not last long. In Singapore, for example, some early adopters were starting to become disenchanted with the format.

In a conversation with KrASIA, a popular streamer who goes by the handle “Junn0215”, shared that he first started broadcasting on BIGO Live around late 2015. As a full-time foreign music student studying in Singapore, Jun turned to live-streaming to connect with like-minded people.

His content varied among music, cooking and chatting. He also started a new concept and held his own version of American Idol on BIGO Live, which became popular. But he soon ran into some disagreements with BIGO Live’s management team.

Jun revealed that a BIGO’s team flew down from China and offered to sign him on as a contract streamer, which would have given ownership of his content to BIGO Live, an agreement he did not want to enter into. Eventually, Jun left BIGO Live in 2016, only to join its competitor BeLive later.

Another live streamer, Lc, told KrASIA that he too left BIGO Live as the community there was “too gangster for [him]”, and that he felt bullied by the company and its community.

Streamers in Singapore started leaving BIGO Live in 2016—which was the dominant player then—either to join other platforms or quit live-streaming altogether, according to the two former BIGO users.

In response to KrASIA’s request for comment on the allegations, BIGO acknowledges that were were a small number of complaint cases at that time, but that they do not reflect the whole picture BIGO’s relationship with the broadcasters.

Loops Live, another IRL live streaming platform, entered the Singapore market in 2016 and tried to poach several live streamers like Lc who had created a big fan following on BIGO Live.

“Loops [Live] gave me more exposure but because it [was] a new company and their advertising wasn’t strong enough, not many people knew it existed,” Lc said. It did not last long in Singapore before it had to quit the market. The company confirmed with KrASIA that it no longer operates in Singapore.

Virtual gifting model: not for every market

IRL live streaming is typically built around the virtual gifting revenue model.

The mechanism is simple. Viewers send virtual gifts they bought using real money to content creators during a live broadcast show, and the platform takes a share.

Virtual gifting works because gifting is psychologically rewarding in that it creates a bond between the viewer and broadcaster, feeding into the fan’s desire for recognition. At the same time, it is also an affordable way for fans to show appreciation to the people they follow since virtual gifts can cost as little as USD 0.01 to USD 0.02.

This model works in China’s USD 5 billion live-streaming industry, but in Southeast Asia, it has yet to be proven.

One difference in the way virtual gifting works in China versus Southeast Asia is that the former has a higher number of so-called “whales”–people who splurge on very expensive gifts for streamers.

In an interview with KrASIA, Kenneth Tan, the co-founder of BeLive, said that in markets where it is active, like Singapore and Vietnam, super-spending whales are uncommon. Without them, the model becomes less attractive for content creators, because earning only piecemeal, small gifts may on the long term not be sufficient to justify investing a lot of time into cultivating a fanbase on the app.

Bad reputation

Live streaming ran into another issue in Southeast Asia.

Most platforms’ business model hinges on amateur live-streamers: non-celebrities who share their life with viewers in real-time. This has encouraged an environment where streamers tend to be young and attractive and their viewers are typically male.

In Singapore, watching a live stream and sending the broadcaster a virtual gift is often likened to the phenomenon of “diao hua” or hanging flowers—a colloquial term referring to gifting a garland to a hostess as a means of tipping her—which carries a negative connotation. Live streaming was seen as an online version of “diao hua” with the same negative image.

Not just in Singapore, across Southeast Asia, concerned viewers pointed out the vast amounts of sleazy content on several live streaming platforms. While content is diverse and can be broadly categorized into music and entertainment, chatting, and food consumption, among others, it’s the content that ranges from nudity to pornography that gives these live streaming platforms a bad name.

But at the same time it was this type of content that initially gave platforms like BIGO their popularity boost around 2016 and 2017.

“I noticed the BIGO [Live] ad because it looked fun, I stayed for the nudes,” Vice quoted an avid BIGO Live user named Bowi Artgita at that time. The article called BIGO “the app that is fuelling the sugar daddy boom“, while in Malaysia, it became known as the “social media prostitute“.

During the time of heightened scrutiny , BIGO Live was temporarily banned in Indonesia and has had to block hundreds of thousands of “negative content” items over the past years.

Live streaming platforms have adopted a zero-tolerance policy for indecent content and use technology to filter it out, but the real-time nature of these streams makes them difficult to police. BIGO told KrASIA that it has a 1,000-people strong moderation team located around the world working round the clock on a daily basis to identify, remove, and ban illegal content and its creators.

Short video, gaming, and shopping live-streams gain momentum

When live-streaming had its hype moment in Southeast Asia the industry and investors were optimistic. This is what encouraged new players like Saudi Arabian IRL app Loops Live to come into the region.

When BIGO Live found itself plagued by nudity scandals, BeLive came to the rescue as an alternative platform and marketed itself as the platform for clean content. It managed to attracted some BIGO Live streamers to move to its platform, but it wasn’t enough for BeLive to sustain.

And live streaming itself faced competition from platforms offering new entertaining video formats, such as Instagram’s stories, and short-video apps like TikTok.

While creators and audiences fragmented across multiple platforms, live streaming itself also split into several sub-genres.

Gaming is another area where live-streaming has gained traction. So far, Youtube Live and Twitch remain the more popular options in Southeast Asia for gamers who are interested in live broadcasting their games. As the domestic e-sports and video game scene grows, it’s likely that some of the Chinese game live-streaming apps like Huya, which is also part of YY, and Tencent-backed Douyu will take note and attempt to capture this audience.

Another avenue that shows promise in the region is live streaming in the context of online commerce, which can be as simple as a Singaporean fishmonger selling fish live on Facebook.

E-commerce firms like Shopee and Lazada are starting to integrate live streaming features on their platforms, so that sellers can reach out to potential buyers directly, ushering in an era of “shoppertainment”.

BeLive has jumped onto the bandwagon of online shopping and pivoted from its consumer-focused live-streaming model to providing live video services for global e-commerce companies such as Rakuten, Loreal, Lazada, and Samsung.

According to Tan, the decision for such a pivot was tough but necessary given the size and lack of potential BeLive found in the Southeast Asian market.

The live streaming industry the region is almost exclusively funded by big Chinese firms who bring experience and deep pockets, which means they afford to keep investing into the platform until a more mature ecosystem of fans and creators forms.

BIGO Live is a spin-off of China’s live-streaming pioneer YY, and Thailand’s Kitty Live is backed by Chinese mobile Internet firm NewBornTown. BeLive had secured money locally.

BIGO with its broad IRL live-streaming approach remains the biggest player in the region. It’s still highly optimistic about its appeal in Southeast Asia, although in the long run, BIGO is not ruling out delving into opportunities surrounding e-commerce and gaming, a representative told KrASIA. And BIGO has learned to play nice with regulators. According to an SCMP report, it has begun offering its censorship technology as a service to the governments of Southeast Asian countries to help them filter offensive content on a larger scale.