Shozo Saito, a 71-year-old former CEO of Toshiba’s electronic device group, has long been frustrated about the decline of Japan’s semiconductor industry. “Japanese chipmakers are becoming less competitive,” Saito laments.

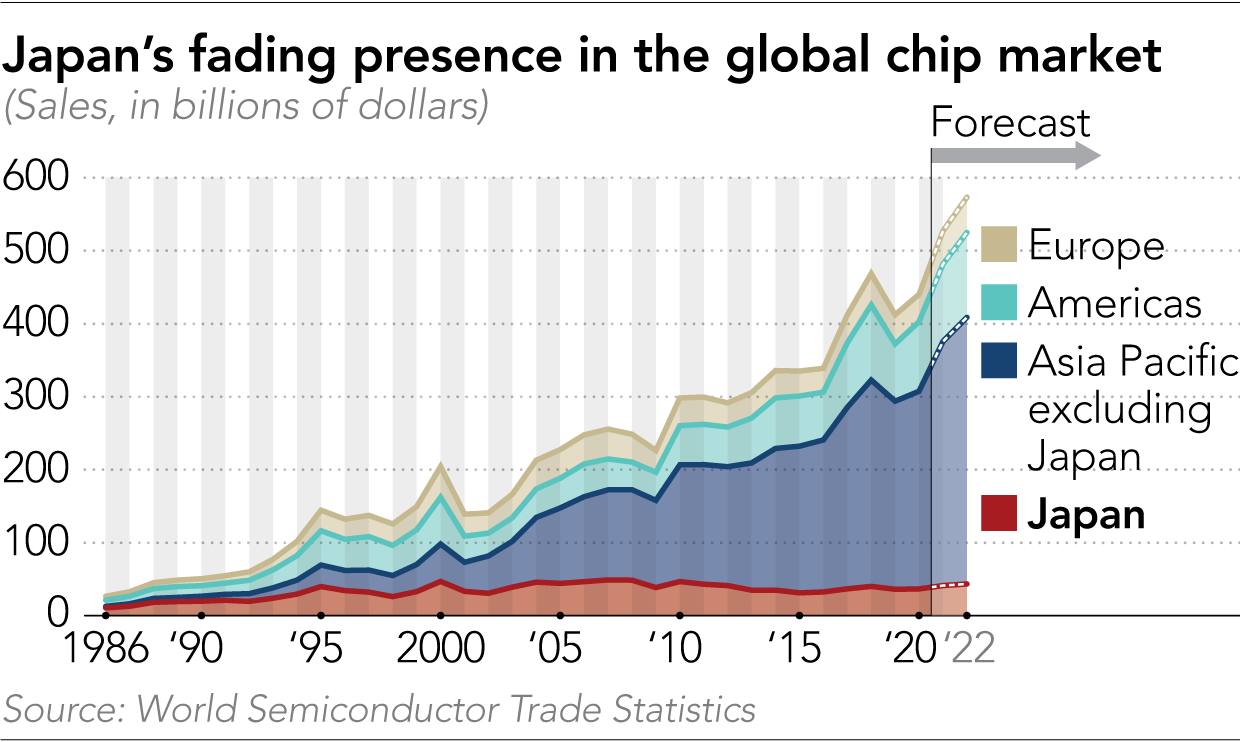

When he was with Toshiba, Japan had a global share of more than 50% in the semiconductor market, thanks partly to memory chips that Saito’s own group commercialized. Today, Japan’s share has slid to 10%, data from the Semiconductor Industry Association show—and the country suddenly finds itself at a crossroads.

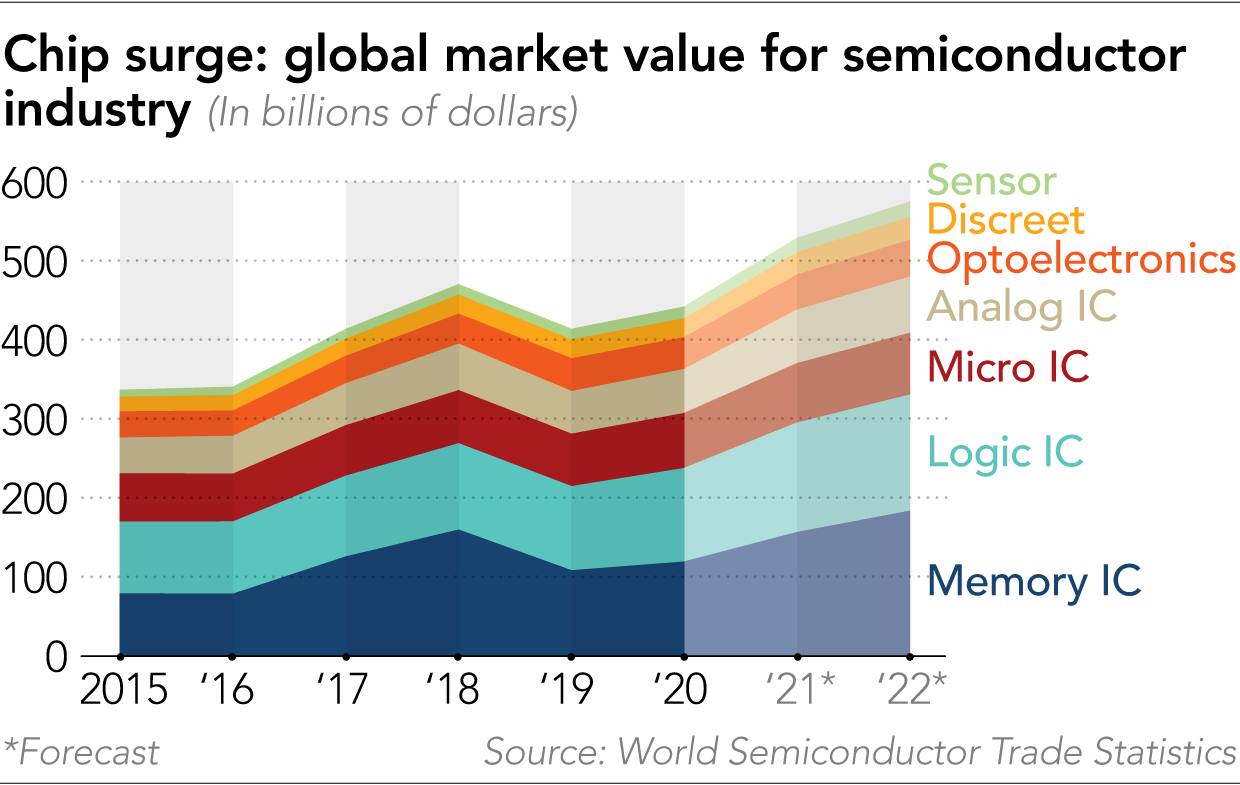

Government policy in South Korea and China is aimed at expanding domestic chipmaking, and the US and Europe—alarmed by this year’s chip shortage and possible geopolitical risks over Taiwan, the biggest source of global supply—are trying to revive their own industries.

The flurry of activity overseas threatens what is left of Japan’s market share — and worse. Industry officials worry that as countries develop their own supply chains in their own territories, related industries where Japan still has globally competitive niche players, such as chip-equipment makers and materials suppliers, will also relocate to these countries, further hollowing out Japanese industry.

Takeshi Hattori, a semiconductor consultant and former Sony engineer, says Tokyo needs to show leadership. “In the US and South Korea, the president is taking the lead in strengthening the semiconductor sector,” he said. “What about the Japanese government?”

Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s government promised to act but, even before the uncertainty over who will succeed him, there were doubts about the strategy set out so far and whether the government has the political will to follow through. There are also real questions about what Japanese companies will realistically be able to achieve.

Until recently, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry had followed a laissez-faire approach. Saito recalls having been told at METI that “semiconductors are something that can be bought from Taiwan.” That attitude has shifted 180 degrees.

To protect and build on the country’s strengths in raw materials, semiconductor packaging, and chipmaking equipment, Tokyo wants more chip production in Japan, which is one reason why METI has led talks with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the world’s largest chip foundry, about locating a factory in the country.

In its national growth strategy released in June, the Japanese government promised support for the development of chip design and production by domestic players, too. Specifics, including the amount of support, await the fiscal 2022 budget discussions that will start later this month. It is also yet to flesh out talks of collaborating with allies overseas, such as the US and the European Union.

Experts point out that there are other issues to deal with, such as pushing the industry to consolidate around one or two “national champions,” and finding corporate managers who can lead the turnaround.

And the government has already made clear that its commitment only goes so far.

“The Japanese government, including cabinet ministers, has a high level of interest in the semiconductor strategy,” said Masayoshi Arai, director-general at METI’s commercial and information policy bureau, which is responsible for overseeing the semiconductor industry. “Ultimately, however, it’s up to business. The government cannot make semiconductors.”

As for investors, it is unclear whether they are on board. “A lot of people believe that chip production is unnecessary,” said Hattori, the former Sony engineer. “The stock market cheers when a company decides to exit the semiconductor business.”

According to market research company IC Insights, Japan had the most chip plant closures of any country or region between 2009-2019, followed closely by North America.

The decline of the Japanese chip industry parallels that of the electronics industry, which lost ground to challengers such as South Korea and Taiwan in personal computers, TVs, and smartphones, among others. Without customers at home, the Japanese chip industry started losing focus.

Toshiba itself sold off more than half its stake in its flash memory business to a Bain Capital-led consortium in 2018 to pay for a restructuring, although it still retains 40% of the business, now called Kioxia. Western Digital of the US, a production partner with Kioxia, has proposed a merger, a politically sensitive deal that will likely need the blessing of the Japanese government.

A year ago, Toshiba also announced it was exiting from system LSI manufacturing, leaving 770 workers redundant. This was followed by news that the company was considering selling two legacy chip plants to Taiwanese foundry UMC.

Sony, while still the leader in image sensor production, sold off its other semiconductor businesses as long ago as 2007. Fujitsu has sold its flagship plant in Mie Prefecture to UMC. Last year, Panasonic exited chip production, selling off three plants in Toyama and Niigata prefectures to Taiwan’s Nuvoton Technology.

Renesas Electronics, Japan’s largest manufacturer of processors, announced the closure of two legacy plants this year, a move that will reduce its chipmaking plants in Japan to seven from a peak of 22. The company is not even thinking about making a major investment in production capacity. “There is no change to our fab-lite business model,” CEO Hidetoshi Shibata said in April, referring to its policy of outsourcing the most capital-intensive part of production to foundries.

Japanese chipmakers didn’t go fully “fabless,” unlike their US counterparts Texas Instruments and Qualcomm. What manufacturing capacity has been retained can be modernized and made more efficient and cost-competitive, turning Japan into an additional source of chip supply for the rest of the world, some argue.

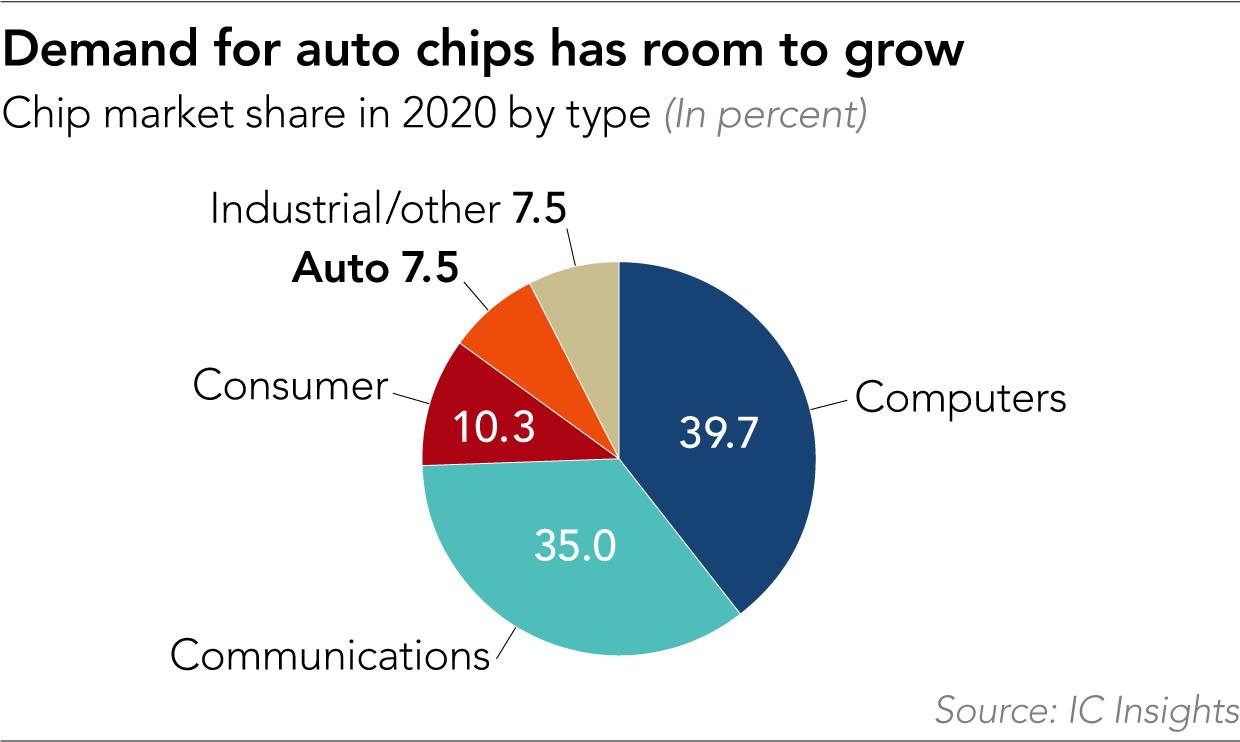

“Japan has to make clear why it needs a strong semiconductor industry,” said Hideki Wakabayashi, a professor of technology management at Tokyo University of Science and a key member of METI’s semiconductor strategy panel. He argues that Japan’s semiconductor industry still has strengths, such as automotive chips and those specializing in power management, which could be used to help the rest of the world achieve the shift to electric vehicles and the “low-carbon economy.”

Semiconductors are important components in cars and will be more so in the future, Wakabayashi predicts. Graphic chips and image sensors are currently used only in smartphones and computer games, but they will be mounted on cars in the future as they become more connected and autonomous, he says. “This is a market Japan must cover,” he said. “Without semiconductors, Japan cannot make cars if they want to.”

Chips used in cars and industrial robots are supplied by Renesas Electronics, which fabricates 60% to 70% of its chips in-house and subcontracts the remainder to foundries such as TSMC. At present, automotive chips only require processing technologies between 20 and 40 nanometers, but in the future, they are likely to require chips in the 10-nanometer class. That is a level of miniaturization well beyond Renesas’ capabilities; it subcontracts anything smaller than 40 nanometers.

“Countries like Japan need first to clarify their objectives: Do you want to develop bleeding-edge technology, or are you looking to secure enough capacity for a number of older-generation technologies to control your own destiny for day-to-day applications, such as industrial, automotive, appliances etc.?” said Jean-Philippe Biragnet, partner at Bain & Co., a global consultancy. “Developing your own bleeding-edge technology is very hard and very expensive—only very large and technologically advanced players like TSMC, Samsung, and Intel may be able to do it,” he told Nikkei Asia.

Even maintaining basic chipmaking capability will be expensive. According to Wakabayashi, it would require investment worth up to USD 50 billion over the next few years for Japan to keep its 10% share in semiconductor production.

Potential sources of capital include telecom carrier NTT—which is developing light-based chips with Sony and Intel in the hope of making the technology the standard for 6G networks—and overseas investors or the state-backed Japan Investment Corporation, according to Wakabayashi. One idea, he said, is to establish a “national security investment fund” between the US and Japan.

Hattori, the former Sony engineer, argues that human capital in the semiconductor industry has been depleted through years of restructuring, and that the rebuilding must start at the university level. He suggests offering scholarships or employment promises at companies like Sony for students who study in fields related to semiconductors.

Wakabayashi, the METI panel member, agrees that incentives are necessary to attract engineering talent. “When students hear about semiconductor engineers being made redundant, they naturally avoid going into the semiconductor industry as a career,” he said. Wakabayashi himself is an engineering graduate who chose to work in investment banking.

Meanwhile, Saito, the former Toshiba executive, is doing what he can. He is now head of the Nippon Electronic Device Industry Association, which he helped found in 2013. Working out of a small, modest office in Tokyo’s Akihabara district, the association offers seminars and helps companies to start new ventures.

“Grassroots activity is our most important mission,” Saito said. “How can we rebuild the industry? It cannot be done by one company, or even by a few companies. Semiconductor production requires horizontal cooperation among many companies. I wanted to do something to help rebuild this industry,” Saito says.

He also has a word of advice for the Japanese government.

“Speed is everything in the semiconductor industry. My concern is the pace of change in Japan. The government needs to outpace other countries in terms of support and scale.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.