When he was a naughty second-year junior high school student in the southern Philippine city of Davao, Reb Buendia’s life changed forever.

He acquired his first smartphone, a tool he now has trouble putting down.

On April 30 this year, Buendia, now 21, spent 14 hours and 23 minutes on his smartphone.

He often finds himself glued to his phone while dining with his family, shopping, or attending university classes. He chats with pals on Facebook, watches videos, and makes video calls before going to bed, usually after 2 a.m.

“I can do anything on my smartphone,” Buendia said. “There’s no way I could live without it.”

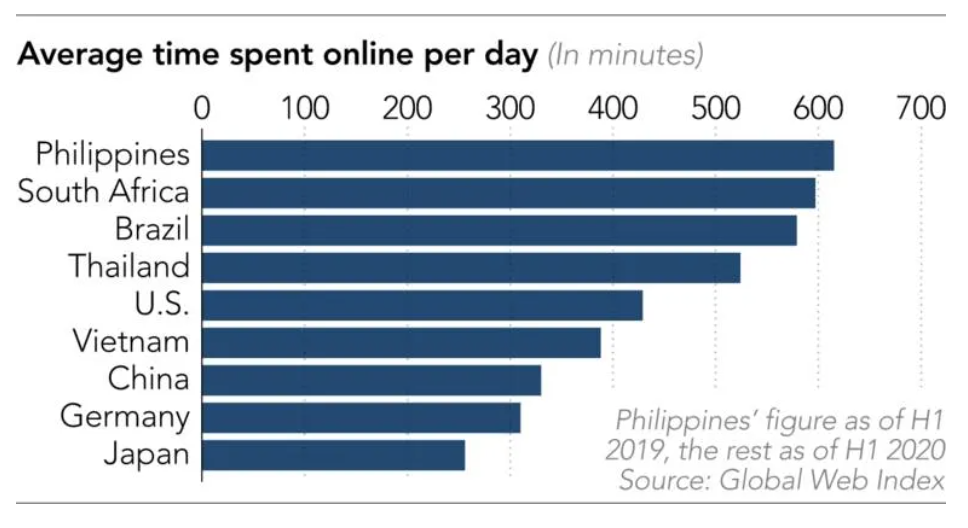

In 12 of the 42 countries covered by a 2020 survey on media usage by GlobalWebIndex, a London-based audience targeting company, people spent more than half their waking hours in a digital space.

Filipinos spent more time, over 10 hours a day on average, using computers, smartphones, and other digital gadgets than their peers in any other country. Other emerging countries where smartphone usage has exploded in recent years—Thailand, South Africa, and Brazil among them—also rank high on the list.

The global shift toward the digital lifestyle is accelerating, partly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the trend could end up costing plenty.

Longer hours spent working on the computer have started taking a heavy toll on the mental health of Kaito Yamada, a 37-year-old employee at a mail-order company in Tokyo.

In early December 2020, Yamada noticed that he was shedding tears as he was suddenly gripped by a sense of emptiness. “Why can’t I stop crying?” he asked himself. His instinct said he was experiencing depression.

For a year and a half, he had been in charge of the company’s web design. As the pandemic forced him to work mostly from home, his on-the-job hours grew longer, often extending to midnight. He had trouble communicating with people around him and began to feel isolated.

Yamada is far from alone in struggling to come to terms with the effects of digital technology on mental health.

The expanding use of digital technology is having far-reaching consequences.

A survey of 3 million workers around the world by Harvard Business School has found that the average number of hours a person works per day has increased by 48.5 minutes, while the number of business meetings has risen 12.9%.

Toshinori Kato, a brain functional physiologist, says teleconferencing could actually lower productivity, not raise it.

That is because it is more difficult to detect subtle changes in people’s expressions or other emotional signs while video chatting than it is at face-to-face meetings. Consequently, it takes longer to guess the intentions of others taking part in a video conference.

“The human brain is not yet fully adapted to the latest technology,” Kato says. He warns of a “trap of digitization,” which can result in a societal decline in overall productivity.

The world is becoming more digital. This inevitable shift to the virtual world cannot be stopped, regardless of whether it leads to evolution or degeneration of the human race. Not everybody is flinching at this prospect.

Peter Scott-Morgan, a British scientist and robotics expert, has lived a life as a “cyborg”—part-man, part-machine—for the past one-and-a-half years.

Since he was diagnosed with Motor Neuron Disease, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, which results in the progressive loss of motor neurons that control voluntary muscles, he has used cutting-edge technology to transplant almost all his physical functions into machines.

Scott-Morgan has made a smooth transition from the physical to the digital world with his digital avatar, which looks and speaks exactly as he does. The virtual avatar moves its lips in time with his speech and gives facial expressions.

He is on a mechanical ventilator and a feeding tube with an artificial anus attached to his colon. Instead of feeling severely constrained and restricted, however, he is enjoying the amazing outcomes of creating “Peter 2.0.”

“I can talk clearly with my mouth shut—in any language. And I can sing with a range larger than any professional singer. I’m also finding myself working seven days a week, harder than at any time in my career. My Peter 2.0 persona will never age,” he said.

The digital space has the potential to allow people to be freed from physical restrictions and overcome the barriers of space and time as well as all kinds of disabilities.

It could become a powerful tool for creative activities that have the potential to unlock new human potentials.

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.