India, a country of contradictions, offers a freedom unmatched in many parts of the world. It’s a place where, despite crackdowns, sexual crimes remain disturbingly frequent. Its cities sprawl unchecked, and policies affecting foreign businesses sway unpredictably. Regulatory enforcement? Often inconsistent at best. If you were to slot India into a Myers-Briggs personality framework, it might come out as a “P”—more perceiving than judging, with an openness to whatever comes its way.

In 2017, Indian media buzzed with claims that the country was on a mission to embrace electric vehicles. Fast forward four years, and an ambitious roadmap appeared, one that put a bold “Made in India” stamp on its vision of widespread EV adoption.

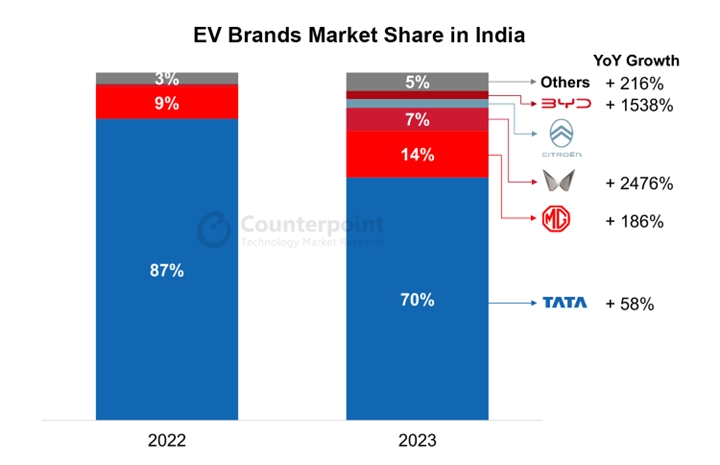

Now, with 2023 in the rearview mirror, it’s clear that the journey hasn’t gone as planned. EVs account for a mere 2% of all vehicle sales—far from the lofty goal of hitting 30% by 2030. The clock is ticking, and India is racing to make up for lost time.

The price of falling behind

India’s answer to this sluggish progress has largely involved subsidies. In September, Reuters reported that the Indian government approved an INR 109 billion (USD 1.3 billion) subsidy package to encourage EV adoption, part of a larger effort to curb pollution and push toward clean energy.

But subsidies alone won’t cut it. India has also turned to its powerful neighbor, China. Livemint noted that Tata Motors, India’s flagship automaker, will source EV batteries from Chinese suppliers in an effort to tackle performance issues and diversify its supply chain.

Then came perhaps the boldest step yet: in March 2023, India rolled out a new policy inviting foreign automakers to set up local factories. The offer? Commit to an investment of at least USD 500 million, start production within three years, and get to export up to 8,000 EVs annually—all while enjoying a dramatically reduced tax rate of just 15%. This compares favorably to the steep 70–100% import taxes that foreign carmakers typically face.

India knows it can’t compete globally in the EV space without a robust supply chain and R&D. The strategy is clear: attract foreign expertise, localize it, and eventually take control of the technology.

On paper, India has plenty to offer potential investors—a consumer base of 1.4 billion, one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, affordable labor, and the world’s largest cohort of STEM graduates.

But the realities are more complicated. For Chinese automakers, exporting EVs to India is one thing. Building factories? That’s a whole different challenge.

Is India a “graveyard” for foreign firms?

China’s automakers aren’t the first to be burned by India’s tricky business environment.

Xiaomi, the Chinese smartphone giant, is a case study in what can go wrong. Despite leading the Indian market for years, Xiaomi found itself under investigation in early 2022. India’s Ministry of Finance accused the company of dodging INR 5.7 billion (USD 68.2 million) in taxes. A few months later, Indian authorities seized INR 48 billion (USD 574 million) worth of assets, alleging illegal remittances. Xiaomi has been fighting the case ever since.

Xiaomi’s troubles are not unique. Other Chinese smartphone makers like Vivo have faced similar accusations. These actions came at a time of heightened tensions between India and China, and the timing is telling. India’s increasingly hostile treatment of Chinese businesses seems to foreshadow the geopolitical tensions that would flare up in late 2022.

Even though India is now extending olive branches to Chinese EV makers, its overall attitude toward foreign companies has been inconsistent at best—oscillating between restrictive measures and sudden openness. When it comes to Chinese firms, India’s behavior can only be described as adversarial.

For instance, India forced MG to halt investments until it partnered with an Indian company that held a majority stake. The country also rejected BYD’s USD 1 billion investment proposal and demanded back taxes despite the company only selling 1,960 cars in India that year. Great Wall Motor, too, faced obstacles, leading to layoffs and the eventual shutdown of its Indian factory.

Chinese companies aren’t solely the ones that have felt the sting. India has also been tough on other foreign firms. Nitin Gadkari, India’s transport minister, was noted once saying that Tesla could only enter India if it fully localized its production, adding sarcastically that he can otherwise go to China.

Other multinational companies have similarly found themselves on the wrong end of India’s taxation policies. British telecom giant Vodafone, American tech firm IBM, and French spirits producer Pernod Ricard are just a few names that have experienced India’s aggression.

Nearly 3,000 foreign companies have exited India over the past decade. Well-known automakers like Fiat, Nissan’s Datsun, General Motors, and Ford have all withdrawn due to mounting losses.

India’s tough sell to foreign automakers

For automakers, the stakes in India are especially high. Despite the country’s massive population, its car-buying power hasn’t caught up. In 2023, the average per capita income hovered around USD 2,500, putting India on par with where China stood in 2007. By most measures, it’s still a low- to middle-income country.

The much-touted middle class? It exists, but in name only for most. Many Indians live on daily budgets of RMB 14–71 (USD 2–10), spending primarily on necessities. Big-ticket items like cars—particularly EVs priced above USD 35,000—remain out of reach for the vast majority.

And even with recent tax cuts, aimed at luring foreign automakers, the benefits only extend to EVs priced at USD 35,000 or higher. This creates a sharp divide, drastically shrinking the pool of potential buyers.

But it’s not just the economics at play. India’s EV infrastructure is, by all accounts, severely lacking. A report from Bain & Company lays it out starkly: India has roughly 200 EVs per commercial charging station, compared to just 20 in the US and fewer than 10 in China.

The power grid doesn’t help either. Overdependence on coal and frequent blackouts further complicate matters. In a recent survey, two-thirds of households reported unexpected outages, and a third said they face daily power cuts lasting two hours or more.

Then there’s the logistical nightmare. India’s shipping and road networks are notoriously underdeveloped. In Singapore, a shipment can move from port to factory in mere hours. In India, that same journey can stretch over days, delayed by clogged customs and poor transport links.

Will Ford return to India, again?

Despite the hurdles, India’s relentless push for EV adoption is starting to bear fruit—at least for some. Ford, for instance, might be gearing up for another go, marking its fourth attempt to crack the Indian market.

According to Reuters, Ford recently held talks with Tamil Nadu’s chief minister, M K Stalin, about restarting production and exporting cars from India. Just three years ago, Ford shut down its operations, but this renewed engagement signals the automaker may be planning a comeback.

Ford’s relationship with India has been a rollercoaster. The company first entered the market in 1926 but went bankrupt by 1953, strangled by strict import restrictions. It tried again in 1995 through a joint venture with Mahindra & Mahindra, pouring in USD 2 billion over the years. Yet despite decades of effort, Ford’s market share never crept beyond 4%, and by 2020, it had dwindled to just 2.39%. In September 2021, faced with deepening losses and no clear path to profitability, Ford called it quits.

The third attempt came quickly on its heels—by early 2022, Ford returned as an EV manufacturer, even applying for the government’s production-linked incentives (PLI) program. But that, too, unraveled within months.

Now, Ford is back once more, proving that India’s market remains an irresistible prize for foreign automakers. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. India’s persistence has also piqued the interest of others: Hyundai, Leapmotor, and Stellantis are all weighing EV sales in the country.

Tesla has been toying with the idea of a USD 3 billion investment to build a factory, though concrete action remains elusive. Still, Daniel Ives, a well-known Tesla bull and Wedbush Securities analyst, is optimistic, predicting that Tesla will have a factory in India by 2026.

India is placing big bets on EVs, hoping to eventually dethrone China as the world’s top car manufacturing hub. Whether that happens remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: foreign automakers choosing to set up shop in India will need to navigate a storm of regulatory chaos and shifting policies. As for Chinese automakers, they might be better off sitting this one out.

KrASIA Connection features translated and adapted content that was originally published by 36Kr. This article was written by Zhai Fangxue for 36Kr.