For the Indian edtech sector which had a rocky start in the early years of this decade and saw numerous startups fade away for being ahead of their time, there has never been a better year than 2020.

After the world’s second-most-populous country imposed nationwide lockdown in late March due to the rising cases of COVID-19, some 320 million students were impacted as schools and colleges remained shut for the better part of the year. Even as the government allowed educational institutions to re-open in the phased manner mid-October, things are far from being normal as over 70% parents prefer to keep their kids at home.

Digital education platforms have thus emerged as a savior for students and parents. As online education graduated from being an optional mode of studying to a necessity, edtech startups thrived more than any other sector.

According to the data collated by Venture Intelligence, venture capital (VC) firms pumped in USD 1.8 billion—over four times more than last year—in Indian education technology startups between January and November across 60 deals.

World’s most-valued edtech startup, Bengaluru-based Byju’s bagged over USD 1 billion in funding this year, while the country’s second-most valued edtech firm Unacademy secured over USD 250 million, Venture Intelligence data shows. Other edtech startups that landed USD 100 million-plus checks from VCs include Eruditus and Vedantu.

It is no surprise that edtech has emerged as the most funded sector in 2020, attracting almost one-fourth of total VC investments till November. The euphoria surrounding education technology startups is to the extent that some investors fear there is an edtech bubble in making.

The meteoric rise of edtech

The sentiments in the investor community had already begun to shift in favor of edtech last year after early backers of Byju’s including Sequoia and Times Internet reaped about USD 314 million in a partial share sale in the fiscal year ended March 2019. By the end of the year, Byju’s revealed it had become profitable. Moreover, during the year, non-edtech companies like Paytm and Amazon also jumped into the fray betting big on the sector.

Thus online education startups began 2020 on a high note, even before the pandemic hit the country that catapulted edtech space on a staggering growth path.

When schools and colleges shut down in March due to lockdown, edtech startups took this opportunity to grab the limelight by offering free content and video classes to students for a few months. In turn, they saw a steep spike in traffic as home-bound students flocked to these platforms. Moreover, Byju’s acquisition of code learning startup WhiteHat Jr. for USD 300 million in August was hailed as a new milestone in the Indian edtech sector’s journey.

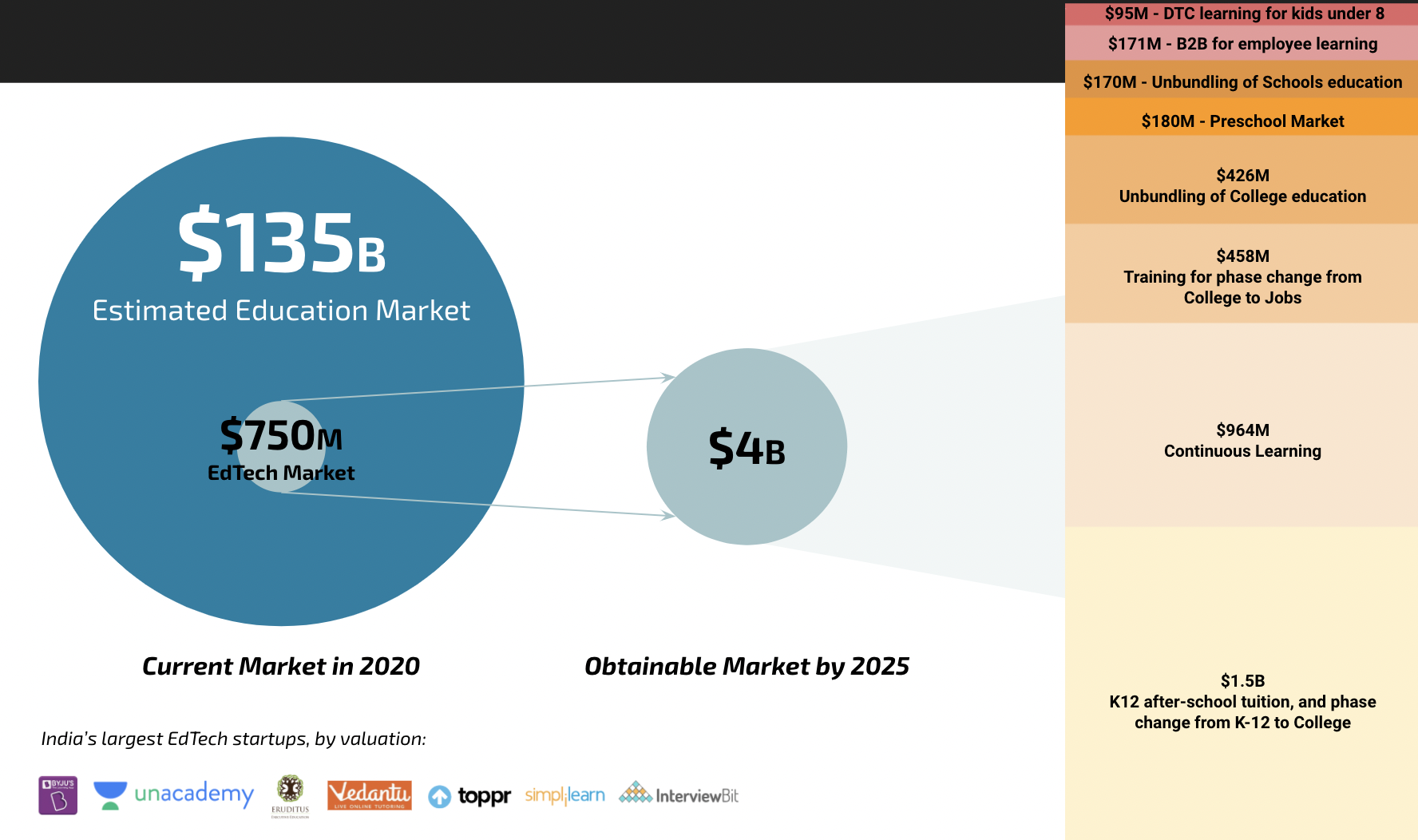

By then, VCs were already hooked on to the online education space. Bullish on the sector’s long-term potential, they were pumping in money in deals at much faster pace than ever before. According to a July 2020 report by Blume Ventures, which has backed edtech startups like Unacademy and Classplus, the country’s edtech market is now poised to become USD 4 billion by 2025 from the current USD 750 million.

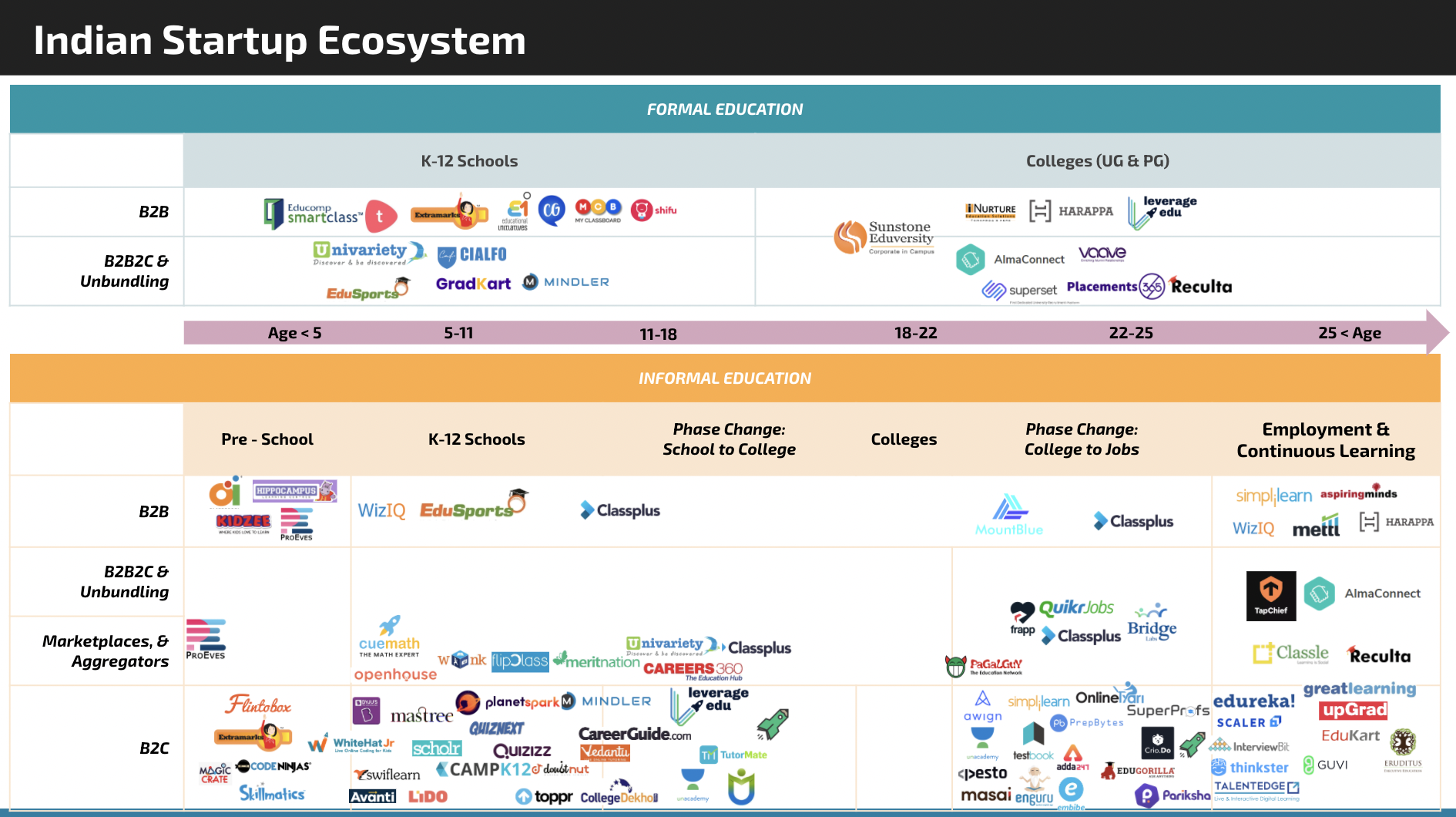

Till about last year, the B2C edtech market was primarily segregated into three broader categories: companies targeting students from kindergarten to grade 12 or K-12, competitive exams and test-preparation platforms, and upskilling firms that focus on learners getting better job opportunities. B2B edtech startups were mainly known to be dealing with schools, selling them ERP (enterprise resource planning) solutions.

During the pandemic, the edtech market evolved to become rather complex as more startups, both new and existing, have risen up to cater to the different needs of learners as well as educational institutions.

Out of syllabus

A cursory glance at edtech startups that were funded this year shows the diverse use cases that have gained prominence. While K-12 and competitive exam preparation markets, are dominated by Byju’s, Vedantu, Toppr, and Unacademy, the non-academic skills teaching market as well as B2B are still up for grabs.

A slew of edtech startups are trying to sell parents the idea that relying on school-led education is not enough for their kids to make it big. There has been an increase in platforms that are teaching computer languages to children, helping them with extracurricular activities, as well as developing their soft-skills. Since, edtech has become the new hot sector of 2020, investors also want to have a pie of this.

Companies like Codeyoung, Codingal, and StayQrious that teach coding to kids, received checks from VCs this year, and so did hobbies and extracurricular activities tutoring companies like Kyt, Uable and Yellow Classes. Then a bunch of startups like Teachmint, ClassPlus, and Winuall that focus on the tutor-side of the digital learning ecosystem have also raised money from VCs.

There are also an increasing number of startups in continuous learning segment which targets employees, retired, or those not formally working, like housewives.

Investors who KrASIA spoke with believe that education will continue to see investor interest as most of the capital so far has gone in generic startups such as those catering to K-12 or test prep segments and not in specific verticals.

“Edtech will remain a strong theme next year, but not because of the big companies,” GV Ravishankar, managing director at Sequoia Capital India told KrASIA. “People recognize that the market is very large and there will be more entrepreneurial activity in edtech. What earlier appeared like niches that are not worth serving, will become deeper markets as more people adopt technology with the belief that they can learn online.”

“There is no longer any question of whether you can deliver education through technology – because schools are doing it. And because they are embracing tech, there is a positive impact on edtech companies,” he added. “Teachers can no longer say edtech doesn’t work – because they themselves are using technology to deliver.”

The making of edtech bubble

That almost USD 2 billion have gone into the education technology sector this year already has also cautioned a lot of investors.

Anirudh Damani, managing partner of VC firm, Artha Venture Fund, who was not very positive about edtech previously, began looking at the segment this year, but discreetly.

“In the past, we had made some edtech investments that did not work out to be as awesome as we thought they would because of inherent problems with the ecosystem,” he said. “The biggest impediment to edtech were teachers and schools themselves, but now they are adopting technology because they had to.”

“So this year, while we started looking at edtech, we don’t want to take that bet yet because we don’t know how schools are going to operate again when they reopen.”

In fact, Damani believes edtech is now in a bubble.

“There has been too much investment in edtech. However, the point here is, how different is an edtech startup from other players,” he said. “For the new edtech startups that are coming up, differences are incremental and not that deep anymore.”

Damani expects a major “shake up” in the segment next year when there will be mergers and acquisitions, while a lot of companies will die down because they are not building anything that is significantly different.

“Once that shake is done, people will realize they have over-invested in the space. At the end of the day, there are only so many apps one person can use for education,” he said. “Eventually, there will be two or three winners in every category, and everyone else will die down.”

“They (edtech entrepreneurs and investors) are all catching a wave, and when people try to catch a wave, many of them also tumble,” he added.

With large players like Byju’s and Unacademy already gobbling up smaller players, it is tough to scale in the edtech business, believes Utsav Somani, partner at AngelList, a US-based digital marketplace that primarily connects angel investors with tech startups for early-stage deals.

“All the new models that are coming up can be very easily replicated by bigger players at scale,” Somani told KrASIA.

That seems to have begun happening. For instance, Toppr, the fifth most-valued edtech company in India, which was earlier focused on K-12 and test preparation, now offers a suite of solutions including coding classes, live group classes for hobbies, doubt solving, and end-to-end operating system to digitize schools.

“Edtech entrepreneurs can enter the space, but their product needs to be different in some way that is truly defensible until they are at scale,” Somani said.

Somani doesn’t see VCs continuing to pump in as much capital in edtech next year. “Edtech is fairly saturated. There are a lot of rounds that have not been announced yet because founders are waiting to reach a certain scale,” he said. These early-stage edtech firms are keeping a low-profile deliberately until they gain good user traction to avoid being copied by bigger rivals.

According to Ashish Taneja, partner at early-stage VC firm GrowX Ventures, the edtech “bubble is already in the making.”

“There are hundreds of edtech startups, of which some 30-40 are reasonably funded,” he said. “At a macro level, it is the extensive number of startups chasing the same opportunity, which essentially means a lot of them will have to be pulled up.”

“We can call it a bubble, but this is a horse race. That’s the rule of entrepreneurship. Everyone can’t succeed,” he said.

Taneja feels big players are buying out smaller ones at very high valuations but said, “sometimes the strategy is to use the money to create dominance.”

Pratip Mazumdar, co-founder and partner, Inflexor Ventures, believes whenever there is this herd mentality in the startup ecosystem, valuations become frothy. “In such a situation, it is hard to make money if the entry is wrong. So for sectors like edtech, we are cautiously optimistic,” Mazumdar said. “Valuations have gone up four to five times (as compared to pre-COVID-19), as a lot of money is chasing these startups. Even if you take an exit later, you may not make that much money.”

Gopal Jain, managing partner at Indian private equity firm Gaja Capital, feels a sector can not be measured based on investor interest.

“It is important to focus on the fundamentals of a sector,” he told KrASIA. “The fact is there has been an acceleration in digital adoption in the education sector. I think when schools and colleges start functioning, we will have to see how much of this acceleration was permanent.”

He feels a substantial part of it will stay. “Blended learning (combination of online and offline learning) was earlier talked about only in the context of higher education, it will now become even core to K-12.”

He believes there might be a consolidation in the sector if investor interest cools off a little after the mainstream education sector opens up. “I really hope this is not a bubble,” he added.