By the time that Dung, the founder and CEO of a hardware startup in Taipei, realized the global tech industry was facing a serious chip shortage, there was little he could do about it.

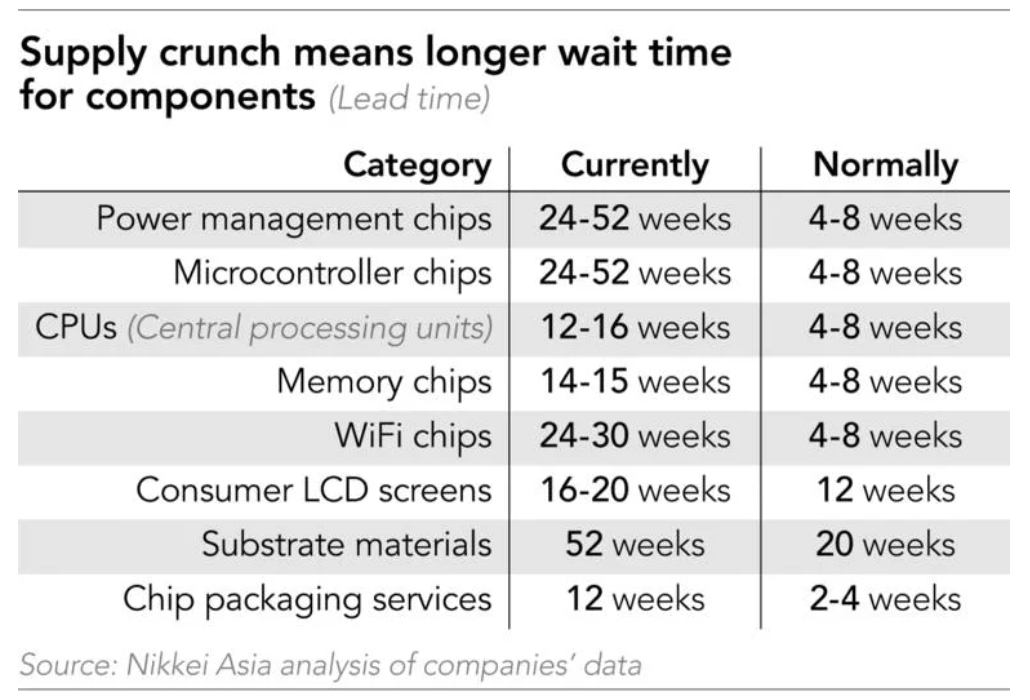

“When I became aware of the real component shortage this January, it was already kind of too late,” said Dung, whose company makes affordable industrial computers. “Some of my suppliers told me that I would have to wait until October or even later for some chips, which I used to be able to order just a month ahead. … That means I may have nothing to ship for almost the whole year, even if I have orders from customers.”

The relatively small scale of Dung’s business means he is one of the early losers in the unprecedented global chip crunch that emerged late last year—in the tech supply chain, larger players have more buying power.

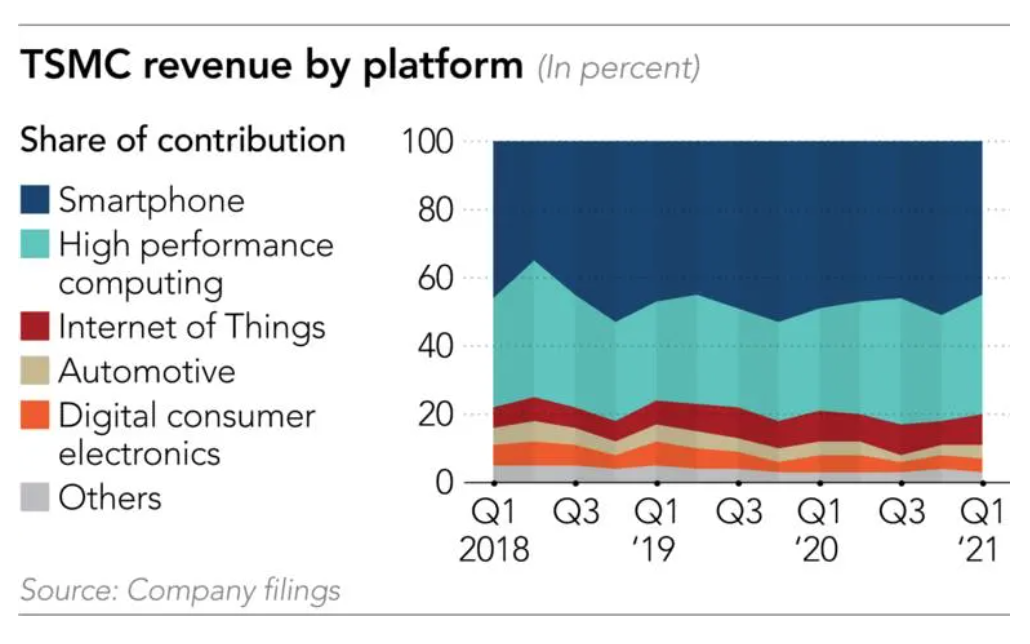

Four months later, the shortage has become so severe and entrenched that it is impacting the likes of Apple and Samsung Electronics, and has even taken on political and diplomatic urgency.

On April 12 US President Joe Biden hosted a meeting at the White House with tech executives from Intel, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and Samsung Electronics, and automakers including Ford Motor and General Motors, to discuss the chip shortage and the resilience of global supply chains.

The supply crunch became a pressing issue for governments when it began to hit automakers earlier this year. The US, Japan, and Germany, the world’s three biggest automaking countries, started pressuring Asia’s key chipmaking economies—South Korea and Taiwan—to prioritize automotive chips, even at the expense of other customers, including smartphone makers and computer manufacturers.

The three governments were wary of automakers having to slow or even halt production due to a lack of chips—threatening domestic jobs and economic recovery from the coronavirus pandemic. Companies like TSMC and Samsung have responded by cranking out chips as fast as they can.

Political pressure to prioritize automakers’ needs, however, has only further squeezed the supply chain, according to industry players.

“We have renegotiated with some of our clients and helped the government’s call to prioritize automotive chips that are important to the global economy,” said Mark Liu, chairman of TSMC. “It’s different from in the past, when [allocation of] chip production capacity was based on a first come, first served principle.”

One result of this chaos is that the already fierce competition in the tech industry has grown even more cutthroat.

“We are telling our suppliers not to give chips to the smaller competitors, and that we will pay higher prices to secure more chips and components. … I am sure my competitors are saying the same thing to the suppliers,” a computer industry executive told Nikkei Asia. “It’s like, ‘If I can’t get enough chips and components, I don’t want anyone, especially my rivals, to get enough of them, either. If I am going to be impacted, I must drag my competitors down, too.'”

Some PC makers even placed orders that were bigger and much earlier than originally planned to soak up capacity and impede their rivals’ ability to secure supplies, Nikkei Asia has learned.

Others are turning on the charm in a desperate bid to keep supplies flowing.

“Even supplies of second or third-sourced components are tight, now. I dined out with the bosses of these suppliers eight times the other week and went golfing with them so many times, pleading with them to prioritize my needs and give me as many supplies as possible,” said a high-ranking executive at Compal Electronics, the world’s No. 2 notebook computer maker.

While the sudden surge in demand from automakers has exacerbated the supply crunch, the roots of the problem go back further.

The outbreak of COVID-19 early last year, which led to lockdowns and quarantines across China, disrupted the tech supply chain. Once deliveries got back on track, electronics manufacturers raced to book more inventory than they would have in the past to ensure they would not be caught short again.

The pandemic also impacted the demand side of the equation. Off-and-on lockdowns and the mass adoption of remote working and learning spurred a massive digital transformation. Adoption of 5G networks and smartphones, which require more chips and components, also picked up speed.

A typical 5G smartphone, for example, has three antennas, compared with one in a 4G smartphone. It also needs 30% to 50% more “passive components” than a 4G handset.

The US-China tech war, which predates the pandemic, has also strained the supply chain. When Washington sharply restricted Huawei’s access to vital US technology, the company stockpiled as many supplies as it could, while it could, and other Chinese companies, fearing similar treatment, followed suit. The result was a massive front-loading of demand for chips and other vital components.

Huawei on Monday openly blamed the US for causing a global crunch, saying Washington’s sanctions on Chinese tech companies prompted panic-buying of components and chips that disrupted the supply chain. “Clearly the unwarranted US sanctions against Huawei and other [Chinese] companies are creating an industrywide supply shortage, and this could even trigger a new global economic crisis,” Eric Xu, Huawei’s rotating chairman, said.

Making matters worse, some Huawei competitors ramped up their orders in hopes of snatching market share from the beleaguered Chinese company.

“Everyone thinks they can grab the full market share that Huawei has lost,” a chip industry executive told Nikkei Asia. Xiaomi, Samsung, Oppo, and Vivo are just some of the smartphone makers that have gained ground globally at Huawei’s expense.

Further US actions followed, including the blacklisting of China’s national chip champion Semiconductor Manufacturing International Co., which counts Qualcomm as well as many Chinese chip developers as clients. Customers worried about SMIC’s ability to maintain supply continuity placed backup orders with other chipmakers, whose production pipelines were already crammed.

The boom in chip orders, reflecting both real demand and defensive bookings, sucked up almost all production capacity for chips and components.

One reason the supply crunch is so difficult to overcome is the long time needed to increase production capacity, either at existing facilities or by building new plants. Intel of the US has announced it will spend USD 20 billion to build two chip plants in Arizona, but these will not go into operation until 2024.

Another reason is that the shortage has started impacting chip equipment makers, meaning that even if companies want to expand capacity, and not everyone is willing to take that risk, they face lengthy delays waiting times for new orders.

Freak disasters such as winter storms in Texas and a fire at a Japanese plant have only made supplies tighter.

Even the biggest smartphone makers have started to feel the squeeze.

Samsung Electronics, which is also the largest memory chip supplier, warned that the situation will be “problematic” in the April to June period. Apple, one of the world’s most powerful procurers, has seen production of some of its MacBooks and iPads delayed.

Peter Hanbury, a partner with Bain & Co. and a specialist in technology supply chains, says the underlying issue is that fundamental demand has outstripped supply.

“In certain segments and technologies, the total demand is exceeding the total supply available, so we now face the even larger challenge of building more capacity which will take three to four years and cost billions—instead of just reallocating within the existing capacity.”

Others, however, are less sure. In their view, the huge amounts of defensive supply orders, frantic stockpiling efforts, and determination to squeeze out rivals threaten to create a massive bubble—and a painful supply glut when it eventually bursts.

“This robust demand will not last forever. People are not suddenly buying five phones or five cars,” said an industry executive in the chip supply chain. “I worry there will be corrections when one of the big guys fires the first shot” and starts cutting orders.

TSMC chairman Liu has already acknowledged that clients are almost certainly double-booking to mitigate the risk of supply chain disruptions caused by geopolitical tensions. However, the company warned on Thursday—when it reported near-record quarterly profits—that the chip shortages could last until 2022.

And that, more than a hypothetical glut, is the problem.

“This serious shortage could be detrimental, especially to many startups and smaller and medium enterprises,” said Wallace Gou, president and CEO of leading controller chip developer Silicon Motion. “Many of them could be out of business if some vital chip supplies could not come in time.”

Dung, the hardware startup founder, admits the clock is ticking.

“We [startups] don’t have the resources and the procurement power like big companies to launch aggressive bids to grab inventories,” he said. “Now we can only work around the clock to change our designs and find some alternative components that are more available—and fight for our survival.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.