A few years after Bom Suk Kim dropped out of Harvard Business School to launch what would eventually become Coupang, South Korea’s largest e-commerce company, he was at a crossroads. He already had a fast-growing e-commerce site on his hands, and was considering taking it public.

Kim had big ambitions: to pivot the company to an Amazon-like model, which he could push even further by building an exclusive delivery network. The problem was that Coupang would need lots of money—likely to the tune of billions of dollars. If the company were to list, investors in public markets might balk at the investment-heavy model.

That was the perfect backdrop for Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank Group. His investment team in Seoul had conducted an analysis of Coupang and its rivals, and found that while others had better cash flow, Coupang had good user experience, according to a person involved in the deal. In June 2015, SoftBank made its move: It injected USD 1 billion into the company, shattering the country’s startup funding record at the time.

Backed by an unprecedented amount of cash, Coupang began building out logistics centers all across the country. That year, Coupang’s revenue tripled from the previous year even while gross profit fell, according to its financial statements.

But that did not stop Son. Having set up the nearly USD 100 billion Softbank Vision Fund in 2017, the investment vehicle injected another USD 2 billion into Coupang in late 2018. The second cash infusion enabled Coupang to launch two more services: grocery delivery and food delivery. As demand surged for those adjacent businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic, Coupang dragged all corners of the industry into a brutal competition.

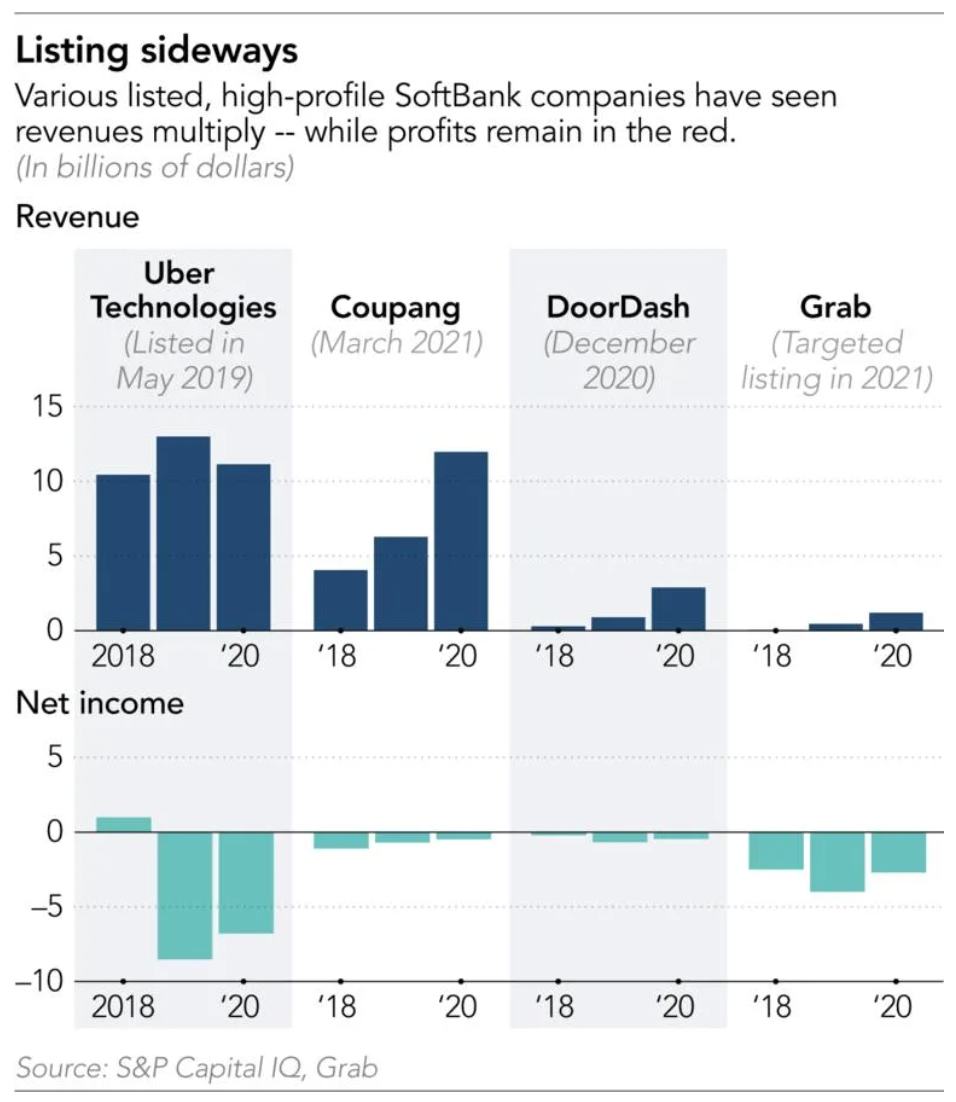

The bet on Coupang now appears to be paying off, at least for SoftBank. Despite recording a whopping USD 475 million loss in 2020, the delivery company’s New York Stock Exchange initial public offering in March gave it an opening market capitalization of over USD 100 billion—more than 10 times the price tag of the Vision Fund’s 2018 investment. That gave the fund massive on-paper gains, helping SoftBank recently report its biggest-ever annual net profit of USD 46 billion.

With blockbuster listings of his risky bets on Asia, Son has defied critics who have said that his aggressive gambles on cash-burning startups would not be embraced by public market investors. Ahead, a slew of potentially lucrative initial public offerings are slated for 2021. At the moment, it is hard to argue, as Son’s detractors have, that his most well-known investment in Alibaba Group Holding—an initial USD 20 million investment that eventually grew to a stake worth over USD 100 billion—was a one-hit wonder. In fact, Coupang’s IPO was the largest by a foreign company in the US since Alibaba in 2014.

In a recent interview with Nikkei, Son said his focus was “completely narrowed down” on making hundreds of new bets on unicorns. His recent pledge to double down on the Vision Fund will test whether investors are finally convinced about his bullish outlook on tech.

Coupled with these successes are notable failures like Greensill Capital, the financial services company which collapsed in March, and WeWork, the hybrid workspace startup whose IPO fell apart in 2019, and these have raised questions about SoftBank’s growth-at-all-costs strategy. Meanwhile, the pandemic has created turmoil in markets, and the outlook for tech stocks remains highly unpredictable. A plunge in investor confidence during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic last year prompted SoftBank to sell more than USD 50 billion in assets, and the same pessimism could return.

Read more: Didi, Grab, and the future of Asia’s ride-hailing giants

The bigger question, however, may be whether the aggressive growth strategy fueled by SoftBank can eventually lead to profitability. Coupang’s investments helped boost its market share in South Korea’s e-commerce market, but competition has remained intense. Startups and major conglomerates are foraying into Korean e-commerce, including Amazon, which partnered with a local e-commerce operator. Coupang has vowed to boost its logistics capabilities by another 50% over the next year.

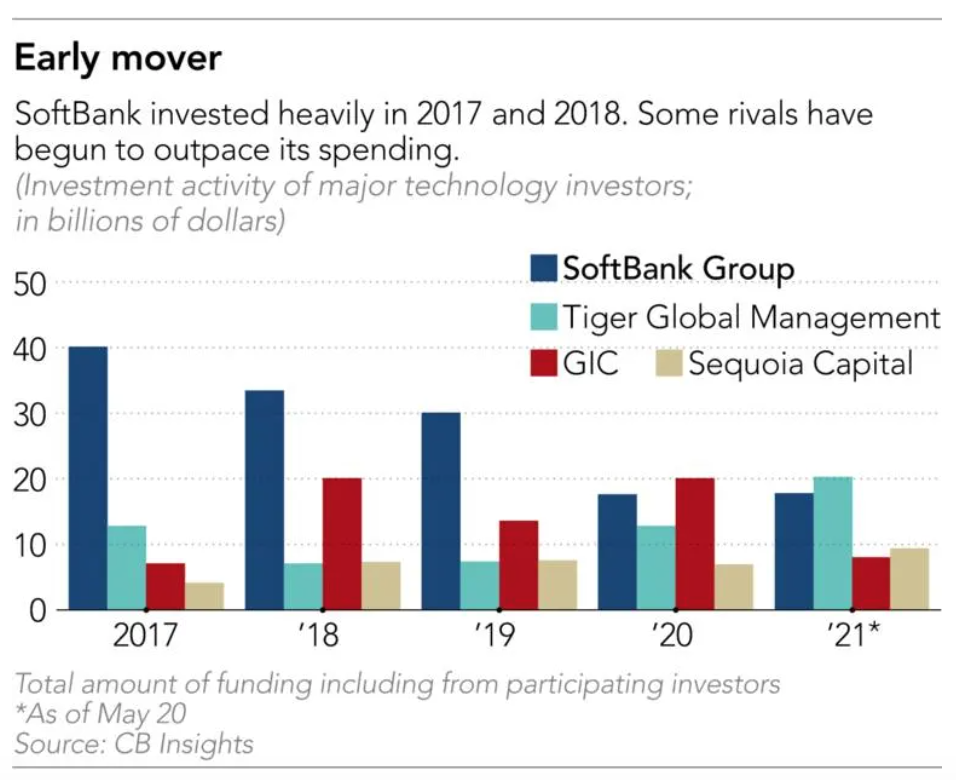

Despite its mammoth pool of capital, Son has also acknowledged that he has been missing out on some of the most competitive deals in the startup industry. Rival investors that won the deals have also reaped massive returns during the pandemic era’s tech stock rally, and are increasingly reinvesting that money to back SoftBank competitors. That makes it difficult for SoftBank to buy into competitors and become a kingmaker if a wave of consolidation arrives.

Those factors are casting a shadow over Son’s ambitions of creating an army of entrepreneurs that will join forces to lead what he calls the “information revolution.”

“There were many investment failures, such as WeWork, Greensill, and Katerra,” Son said. “But what I regret more is the missed opportunities to invest.”

Longsighted or myopic?

Launched four years ago, the Vision Fund, created in 2017 by Son to fuel a shift from telecommunications to tech investment, now spans two funds and more than USD 130 billion in combined assets, including capital committed but not yet invested. From its offices across London, Silicon Valley, Mumbai, and other locations, members of its 26 investment teams hunt for startups around the world. Negotiations over potential investments eventually lead to a meeting with Son, now mostly held over Zoom. It can take less than an hour for him to decide to invest billions.

“Barely 5% of the companies are profitable when we invest,” Son told Nikkei. “Ninety-five percent of companies are lossmaking, and the loss continues to increase. We invest in these companies at huge valuations. You need courage.”

“Usually, it is difficult to make investment decisions based on the so-called traditional financial institution way of thinking,” he said. “One of the reasons we can do it is that we understand the background of technology.”

Son appears comfortable with the risk of both success and stunning failure. Alibaba was lossmaking when he first invested, he pointed out. “We use our imagination. If [the company] uses artificial intelligence in this way and gets customers, it should work. If it makes one mistake, it will fall into the abyss.”

In fact, the seeds of those multibillion dollar bets were planted years before the Vision Fund. Shortly before its 2015 bet on Coupang, SoftBank co-led a USD 100 million investment in Tokopedia, an online shopping site in Indonesia. It also lined up bets into Asia’s nascent ride-hailing industry, pouring USD 250 million in Grab Taxi in Southeast Asia and leading a USD 600 million funding round for Kuaidi Dache in China.

Those companies were later turbocharged with billions of dollars from the Vision Fund. Before it entered the scene in 2017, the landscape was dominated by two broad types of investors. Big private equity funds would buy companies with a stable cash flow, improve their profit margins and sell them, distributing the profits between themselves and the fund investors. Investors in startups, known as venture capital, generally gave small amounts of capital to many companies in hopes that a few will become wildly successful.

The first Vision Fund, which raised more than USD 98 billion, was a unique combination of the two. It invested in the scale of the biggest private equity funds, but targeted fast-growing tech companies with as-yet-unproven business models.

“You are buying time for the company to prove the right business model,” said Oliver Matthew, an analyst at CLSA. “Some of these investments will fail, and they accept that. But the overall level of disruption you can bring through these kinds of companies should offset a minority of investments which fail.”

Take the case of Tokopedia. Led by William Tanuwijaya, a former part-time worker at an Internet cafe, it generated virtually no revenue for the first few years. Indonesia’s poor infrastructure meant the economics of making profits by delivering goods across the archipelago were highly unfavorable.

Scale, however, made a difference. The company began to expand rapidly with SoftBank’s 2014 investment, but the Vision Fund’s turbocharging took it to another level. Tokopedia observed that it was attracting 60 million to 80 million consumers, but many were not actively making purchases. Instead of waiting for income levels to rise, it decided to lower the bar as far as possible for making an online transaction. Pursuing what it called an “infrastructure as a service” business model, it started building out a dazzling array of transaction services: utility bills, train tickets, groceries, and lending, among others.

“The core vision has been clear: How do we bring more of the Indonesian consumer wallet online?” said Lydia Jett, a partner at the Vision Fund who sits on the board of Tokopedia, Coupang and others.

Such an all-out expansion requires burning cash for years, and was too risky for most investors. But Son convinced the sovereign wealth funds of Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi to join the Vision Fund by offering them a 7% annual coupon for half of the money they put in, as well as committing USD 33 billion of SoftBank’s own capital. That exposed SoftBank to a large risk in the beginning—it had to pay billions of dollars before it was able to start cashing out—but gave it the opportunity to profit handsomely if its bets paid off.

The growth-at-all-costs model came under doubt in 2019, after shares in Uber Technologies, one of the Vision Fund’s biggest bets, fell after going public in the US, A few months later, WeWork pulled the plug on its IPO after fetching a USD 47 billion valuation. Concerns over whether its other portfolio companies could survive the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a sell-off in SoftBank’s own shares, prompting Son to announce a massive asset sale and share buyback.

“We overestimated, or were overconfident, about the founder, Adam [Neumann],” Son recalled of his bet on WeWork. Uber’s shares “sold for higher than what we paid for, but the stock price slumped after the listing.”

SoftBank also valued its entire investment portfolio “very conservatively,” Son added, “because [companies] might fall into the coronavirus valley.”

SoftBank’s USD 1.5 billion bet on Greensill Capital, which pitched a “technology-driven approach” to supply chain finance, also soured. Its technology was supposed to enable it to provide short-term financing to companies traditionally deemed risky, but in reality, a chunk of Greensill’s loans went to other Vision Fund portfolio companies. Greensill collapsed after its main insurer did not renew its insurance policy.

“I think the business model of the company is wonderful. I still think so … but there were excessive loans made to certain companies,” which led to a collapse in confidence, Son said. “Some of the companies we invested in were part of Greensill’s lending activities. I don’t know the direct interactions, but we have to reflect on the fact that we accepted it.”

Now, a batch of IPOs slated in the coming months may finally vindicate Son’s strategy.

In April, Grab Holdings announced plans to list through a merger with a SPAC, or special purpose acquisition company, in a deal that values Grab at almost USD 40 billion—the biggest SPAC deal ever. Tokopedia recently announced a merger with Gojek, Grab’s main competitor, and an executive said the combined company plans to go public by the end of this year.

Nikkei has reported that Didi Chuxing, the result of a merger between Kuaidi Dache and Didi Dache, has started working with the US Securities and Exchange Commission toward an IPO on the New York Stock Exchange. The IPO is expected to value the company at around USD 70 billion to USD 100 billion. SoftBank has invested nearly USD 11 billion into Didi Chuxing, fueling its expansion across the country as well as into new areas like autonomous driving and grocery delivery.

WeWork has also announced plans to list via SPAC, raising the chance of SoftBank recovering some of its losses. Zuoyebang and Full Truck Alliance in China and Delhivery and Policybazaar in India are among other IPOs in the pipeline, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

Those investments could be a huge windfall for the Vision Fund. Its stake in Coupang alone was worth USD 27 billion as of March. Combined with a stream of smaller IPOs and the rise in the value of its listed portfolio companies, Vision Fund 1 and 2’s total investment gain for the year ended March was USD 58 billion.

Son has brushed off the record-smashing profit as a combination of lucky events happening at the same time. His focus is expanding the group’s portfolio of “224 companies … to 300, 400, and 500.” SoftBank wants to create what Son calls a herd: “a group of cutting-edge engineers and entrepreneurs who solve every problem in the world.”

That goal will be tested under the glare of public markets. In SoftBank’s world, conventional metrics like profits do not matter. Instead, there is “unit economics”—indicators of future profitability once the cash burning stops. That will converge with the quarterly earnings that will be fed to public market investors.

“You are transitioning from the venture capital and private equity thinking toward the public equity thinking,” said Claudia Zeisberger, a professor for private equity and venture capital at INSEAD business school. “Once the whole portfolio is publicly listed, internal measures are not as relevant anymore.”

Coupang, for example, reported a net loss of USD 295 million for the first quarter, an 180% increase over the previous year. It outstripped the 74% increase in revenue. But based on its own key metric, “spend by customer cohort,” users who joined in 2016 on average spent 3.59 times as much on Coupang in 2020. The fact that existing users spend more every year is a signal that Coupang will turn profitable once it stops building new factories and hiring delivery staff.

“We are very excited to see that customer engagement continues to increase and their spend continues to increase,” said Vision Fund’s Jett, “When we stop, should we ever stop forward investing in the demand that we expect to see, our utilization [of logistics capacity] will increase, and then our profitability will look better.”

Building a track record of IPOs will be key, not only for returns, but for SoftBank’s reputation. “SoftBank has been part of some of the largest e-commerce companies globally,” said Vidit Aatrey, co-founder and CEO of Meesho, an Indian social commerce site that accepted funding from SoftBank recently. “It was a no-brainer for us to say yes to it and move forward.”

Crowded field

SoftBank is no longer the dominant force in backing startups. Vision Fund 2 is currently entirely funded by SoftBank and is a third of the size of the first fund. That has put it in closer competition to a growing number of investors in private tech companies. Mutual funds, and even hedge funds that have traditionally invested in publicly traded stocks, have moved into the field, hunting for yields in an ultra-low interest rate environment.

Early backers of the top unicorns are also doubling down, with the biggest ones outpacing even SoftBank. US investor Tiger Global Management was involved in funding rounds worth more than USD 20 billion this year alone, compared with SoftBank’s USD 17.8 billion, according to CB Insights.

One Singapore-based startup investor said Tiger’s strategy resembles the Vision Fund in that it “changes the rules of the game with cash.” “It is good for disciplined entrepreneurs, but many have moved into fancy offices before turning a profit. There are pluses and minuses.”

Razorpay, an Indian fintech company, is a symbolic example. In the past few months, the company raised capital from investors including Tiger Global Management, GIC, Sequoia Capital, Ribbit Capital, and Matrix Partners—some of the most well-known names in venture capital. Its valuation grew from USD 1 billion in October to USD 3 billion in April.

Razorpay’s popularity has been growing due to its reputation as India’s equivalent of Stripe, a US online payments processor that was recently valued at USD 95 billion. SoftBank is not an investor in either of them.

Even Meesho, which accepted SoftBank’s investment, politely turned down Son’s offer to take more capital, according to a person involved in the talks.

The wild ride from historic losses to record profits has also shown that Son, who now owns nearly 30% of SoftBank Group’s shares, is unshaken by the calls for change. Yuko Kawamoto, an external director that joined a year ago after calls for more governance, is among three board members stepping down in June. They follow a string of high-profile board departures, including Uniqlo founder Tadashi Yanai, who was known for challenging Son.

The new board member candidates come from Son’s inner circle: Keiko Erikawa, a longtime friend, Kentaro Kawabe, who runs SoftBank affiliate Z Holdings, and Kenneth Siegel, a lawyer that has advised SoftBank in its M&A transactions.

In a message posted on SoftBank’s website, Kawamoto explained that her departure is due to her appointment inside the Japanese government. She also said SoftBank “needs to formulate a form of governance that allows Masa to fully demonstrate his talents, which can then be integrated into shareholders’ value.” She also highlighted that SoftBank’s biggest challenge is “to design a succession plan.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.