As Zoom rose to become the pandemic era’s top videoconferencing platform, the US company turned to the Philippines, the world’s call center capital, for customer and operations support.

The company was “seeking a cost-effective solution in the middle of a pandemic” when it launched in Manila late last year, and it has since tripled its headcount, said Gian Reyes, vice president at KMC Solutions, Zoom’s contractor.

Zoom is one of dozens of new contracts won by Philippine business process outsourcing (BPO) companies during the pandemic, enabling the USD 26.7 billion industry to expand despite a global recession.

But while the sector, a pillar of the Philippines’ USD 361.5 billion economy, stands to benefit from companies’ penchant for cost cuts during crises, automation by chatbots and artificial intelligence continue to hang over its future.

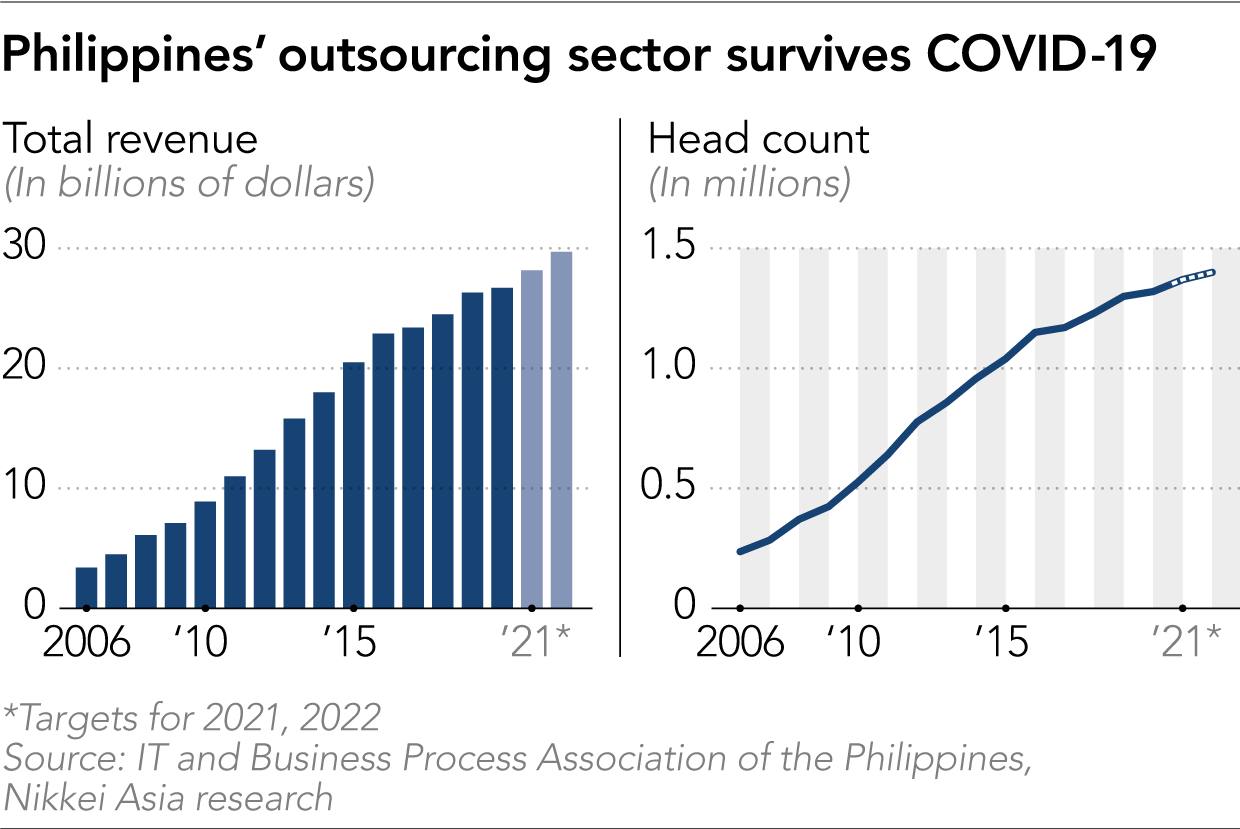

The industry, which includes non-voice services from IT support to animation, as well as call centers, saw revenue rise 1.4% to USD 26.7 billion last year, according to the IT and Business Process Association of the Philippines (IBPAP). After increasing headcount by 1.8% last year, it now employs 1.32 million of the Philippines’ 109 million people. IBPAP forecasts that number will rise to 1.46 million within two years.

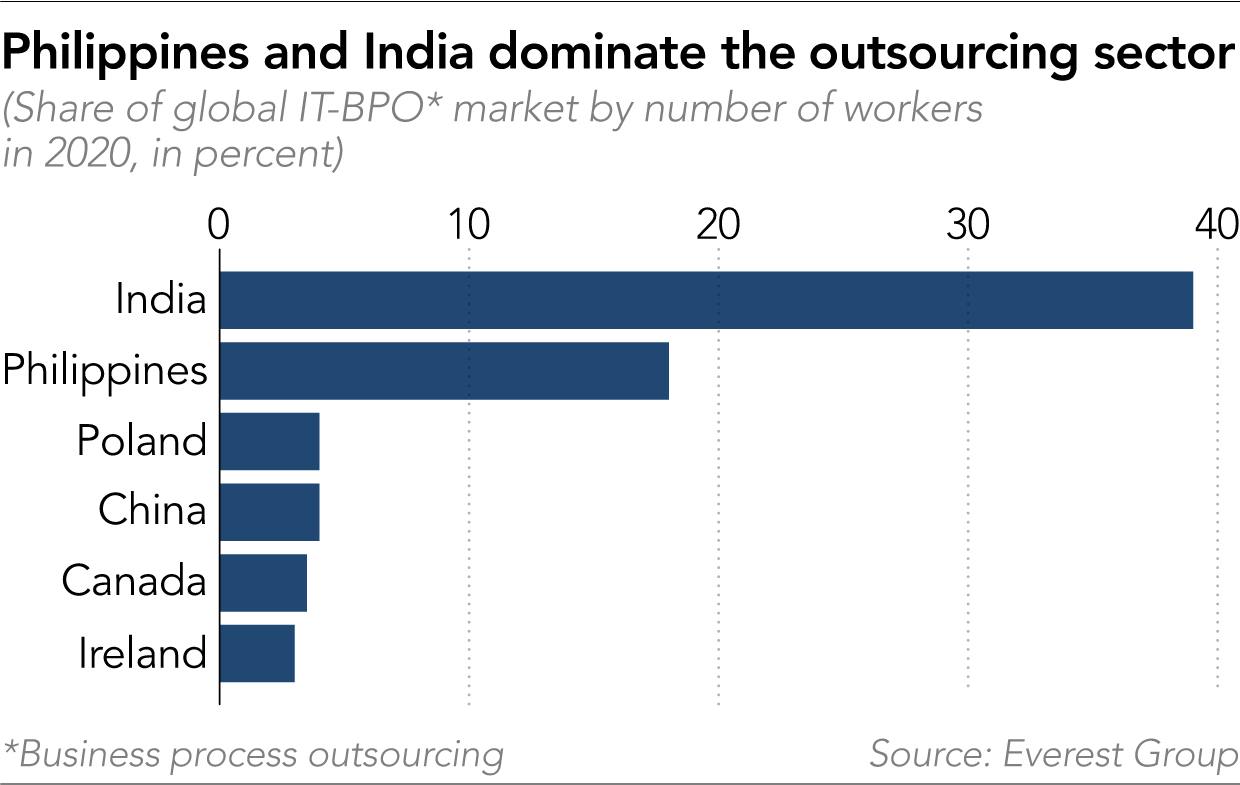

Growth is again accelerating this year. Around 87% of companies surveyed by IBPAP expect revenue to expand by between 5% and 15%, helped by recovering global demand and as the Philippines takes over some jobs from India, the world’s biggest outsourcing destination and Manila’s rival in the BPO segment.

India’s own IT-BPO industry revenue is estimated to have grown 2.3% to USD 194 billion in the fiscal year ended March, its National Association of Software and Services Companies said in February. Nitin Soni, a senior director at Fitch Ratings, expects the industry to expand by 10% in fiscal 2022, amid rising global demand for IT services, India’s specialty.

But India was hit hard by one of the world’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks earlier this year, prompting companies to hedge their bets by rebalancing their geographic footprints, according to Rey Untal, IBPAP’s outgoing president and CEO.

Companies that routed some jobs to the Philippines include a “major search engine company” and an “American retail giant,” according to industry sources who declined to name specific companies due to confidentiality agreements.

California-based BPO provider Concentrix, whose 100,000 staff make it the Philippines’ largest private employer, is among those that shifted work to Manila as India struggled with the virus.

“Assistance to India from the Philippines and multiple other geographies were assessed and implemented according to the clients’ needs, both on a temporary and ongoing basis,” Amit Jagga, head of Concentrix Philippines’ operations, told Nikkei in July.

Jagga said Concentrix Philippines, which serves retail, e-commerce, tech and consumer electronics companies, added “thousands of new seats” after the start of the pandemic, as new and old clients expanded.

Last year’s growth was a surprise. IBPAP had been braced for a small contraction as the virus hammered its clients in the tourism sector, such as airlines, while lockdowns disrupted operations.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte classified BPO an “essential” sector, along with food and health care, when he imposed a lockdown in March 2020, allowing offices to stay open in a limited capacity. The industry relies heavily on large brick-and-mortar offices due to round-the-clock operations and strict data security required by clients like banks.

To sustain operations while the rest of the world hunkered down, some BPO companies housed workers in hotels and private buses ferried them around public transportation was halted. For those who shifted to working at home, telecoms companies installed Wi-Fi and employers provided noise-cancelling software—though some callers still complained of crowing roosters in the background.

By the fourth quarter of last year, demand from the technology, gaming, communications, media, e-commerce, fintech, and health care industries started to soar.

“As social distancing measures limited physical encounters, the relationship between brands and consumers became mostly remote, driving businesses to transform and [become] digital-first, increasing demand for digital and remote services,” said Krishna Baidya, a director at management consultancy Frost & Sullivan.

The BPO industry has historically been resilient during crises, said Derek Gallimore, founder of Outsource Accelerator, an industry adviser. “Outsourcing is fundamentally countercyclical. The industry can do well in recessions and depressions,” Gallimore said.

BPOs weathered the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s, and thrived after the global financial crisis a decade later. In 2010, the Philippines dethroned India as the world’s call center capital by revenue and headcount, and in the years since it has attracted new customers such as Amazon, while established players like Ireland’s Accenture and France’s Teleperformance have expanded. The Philippines now accounts for around 12% of the global outsourcing market by revenue.

The Philippine outsourcing industry has its roots in contact centers set up in the ’90s in which workers responded to customer queries by email. Special economic zones turbocharged the sector with tax breaks. The former US colony also has an advantage, with a young, English-speaking workforce and strong rapport with Americans, the industry’s No. 1 source of client calls.

The industry is an economic pillar for the Philippines—as important as the USD 30 billion in annual remittances sent by 10 million Filipinos working overseas. The BPO industry’s success has benefited sectors from real estate to retailing, transforming sleepy suburbs into bustling business districts.

But BPO also has vulnerabilities. Executives blanched when former US President Donald Trump announced his “America First” agenda, vowing to bring lost American jobs back onshore, and when Duterte told US investors to “pack your bags” amid diplomatic tensions with Washington. Meanwhile, investment stalled during the long debate over a corporate income tax reform bill that streamlines incentives enjoyed by BPO companies. The bill became law this year but the industry was granted a 10-year transition period after intense lobbying.

Technology is also changing the game. Automation, AI, real-time analytics and chatbots are taking over some tasks previously handled by humans. “The use of these tools has become even more relevant during the pandemic,” said Frost & Sullivan’s Baidya. “The industry as a whole needs to think beyond being a pool of English-speaking talent to usher in a new generation … delivering requirements that were unheard of until now.”

Rajiv Dhand, regional vice president at Canada-based Telus International, a BPO company with 18,000 employees in the Philippines, said automation “is not something the company sees as a threat to our team members’ job security, nor the value of the customer experience.” His company opened a new site in the central city of Iloilo this year, its seventh in the Philippines.

“AI is only as strong as our team members behind it,” Dhand told Nikkei. “AI’s effectiveness depends on human judgment.” Workers’ skills are being enhanced to remain competitive, he said.

For now, the pandemic continues to pose as many challenges as it does opportunities, especially as the delta variant triggers record case numbers and new lockdowns. In June, one of the largest known COVID outbreaks in the industry was reported at an unnamed BPO company in the southern city of Davao, with more than 400 workers testing positive.

Many BPO employees have complained of burnout as the new work has poured in. “It’s toxic, stressful and there’s too much pressure,” said 27-year-old Micah, who quit her call center job last month. She asked to be identified only by her first name because she plans to return to the industry after taking a break, underscoring the fact BPO jobs offer better pay than many others. It remains a preferred career for many people.

Remote work will likely continue, even after the pandemic ends. But, said IBPAP’s Untal, “We need to fortify our infrastructure—telco, power, and transport.” Unlike offices, homes don’t have redundant power and internet infrastructure, he said.

The typhoon-prone Philippines is no stranger to brownouts during the rainy season, and in summer when power demand peaks. Its telecom companies are often criticized for slow internet service. Untal has proposed “community-based” facilities or repurposing shopping malls to serve as alternative offices closer to people’s homes.

The industry will also need to step up investment in new technologies and high-tech skills if it is to stay ahead of the chatbots. “This [needs] a whole-of-industry and government approach—[for the Philippines to become] a digital nation,” Untal said. “We are not bullet proof. We still need to do heavy lifting.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.