Cutthroat rivals that have helped to drive Southeast Asia’s rapid digitization by burning through cash and preventing each other from moving toward the startup world’s new goal, profitability, are now talking about a common solution.

Indonesia-based Gojek and Singapore-based Grab, have “casually” discussed merger options, according to two people familiar with the matter. The sources told the Nikkei Asian Review that Gojek co-CEOs Kevin Aluwi and Andre Soelistyo, as well as Grab President Ming Maa, talked earlier this month. There have been no follow-up talks, the sources said.

Several other media outlets have reported that the two companies are involved in such talks.

Grab has declined to comment, while Gojek has said “there are no plans for any sort of merger” and that the reports “are not accurate.”

“As these companies mature,” said Mark Suckling, principal at the Singapore-based venture capital Cento Ventures, “it is natural that their management, along with advisers and investors, look for ways to consolidate their position in markets in which they operate. An acquisition of a smaller rival, or a merger with a competitor is one way to achieve that.”

There is a precedent: Chinese ride hailers Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache merged in 2015 to become what is now Didi Chuxing.

“In 2020,” Suckling said, “there is more discussion among late-stage investors about finding a path to profitability, and it therefore follows that a merger deal which generates additional scale for ride-hailing, and also reduces some competition in the other businesses, makes a good deal of sense.”

That both companies suddenly have at least one common investor adds to the merger speculation. Gojek counts Mitsubishi UFJ Lease and Finance as an investor, while Grab now has MUFG Bank on its capitalization table. Both companies are part of Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group.

The biggest driver, though, might be this: Gojek founder Nadiem Makarim has left the company; he is now Indonesia’s education minister. The rivalry between the two companies has always had an element of personal competition. Makarim and Grab founder Anthony Tan were Harvard Business School classmates.

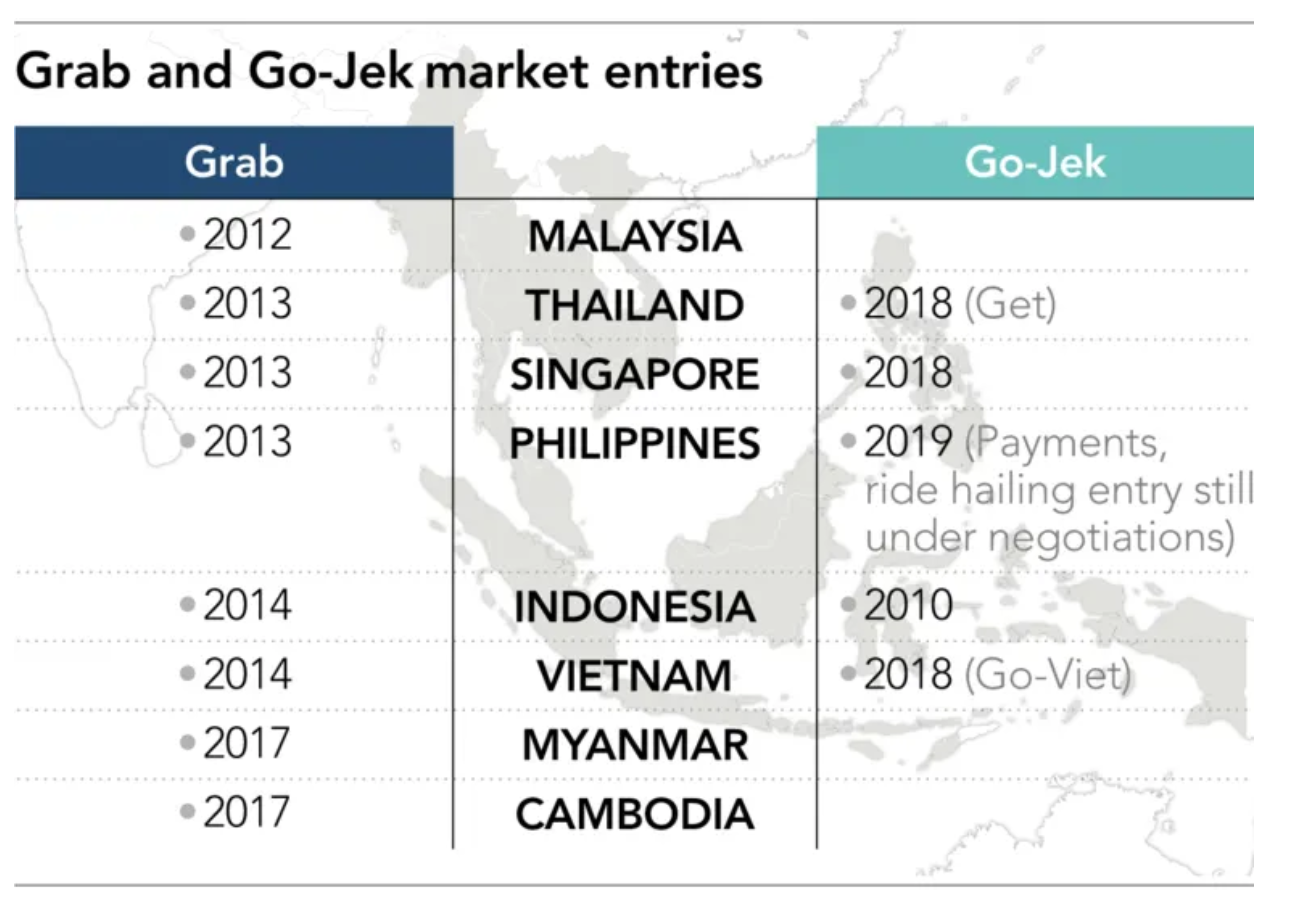

They started their ride-hailing businesses around the same time, Makarim in 2010, and Tan in Malaysia in 2012, when Grab’s precursor was MyTeksi. As both startups grew and Grab expanded into Indonesia, a three-way battle began to unfold, one that included US ride hailer Uber.

In the early stages of the competition, Gojek and Grab seriously considered merging, according to a person familiar with the matter. The talks, however, were dashed after Grab raised a huge amount of funds and decided to go it alone. In 2018, it acquired Uber’s Southeast Asian operations.

Gojek began expanding across borders that same year. The cutthroat competition since then has led the rivals to burn through cash. Although they are now doing so at a much slower pace than previously, the competition remains a hurdle to profitability.

As Gojek and Grab added services, including food delivery, the competitive environment grew toxic. The companies’ services are similar because “they keep copying us,” Makarim told the Nikkei Asian Review in September 2018, when Gojek expanded into Vietnam. “[Grab] consistently outspends us [but is] not able to actually threaten us in any existential way.”

The competition has spread to the payments sector, especially in Indonesia, where Gojek’s GoPay and OVO, in which Grab has a large stake, are locked in a fierce battle.

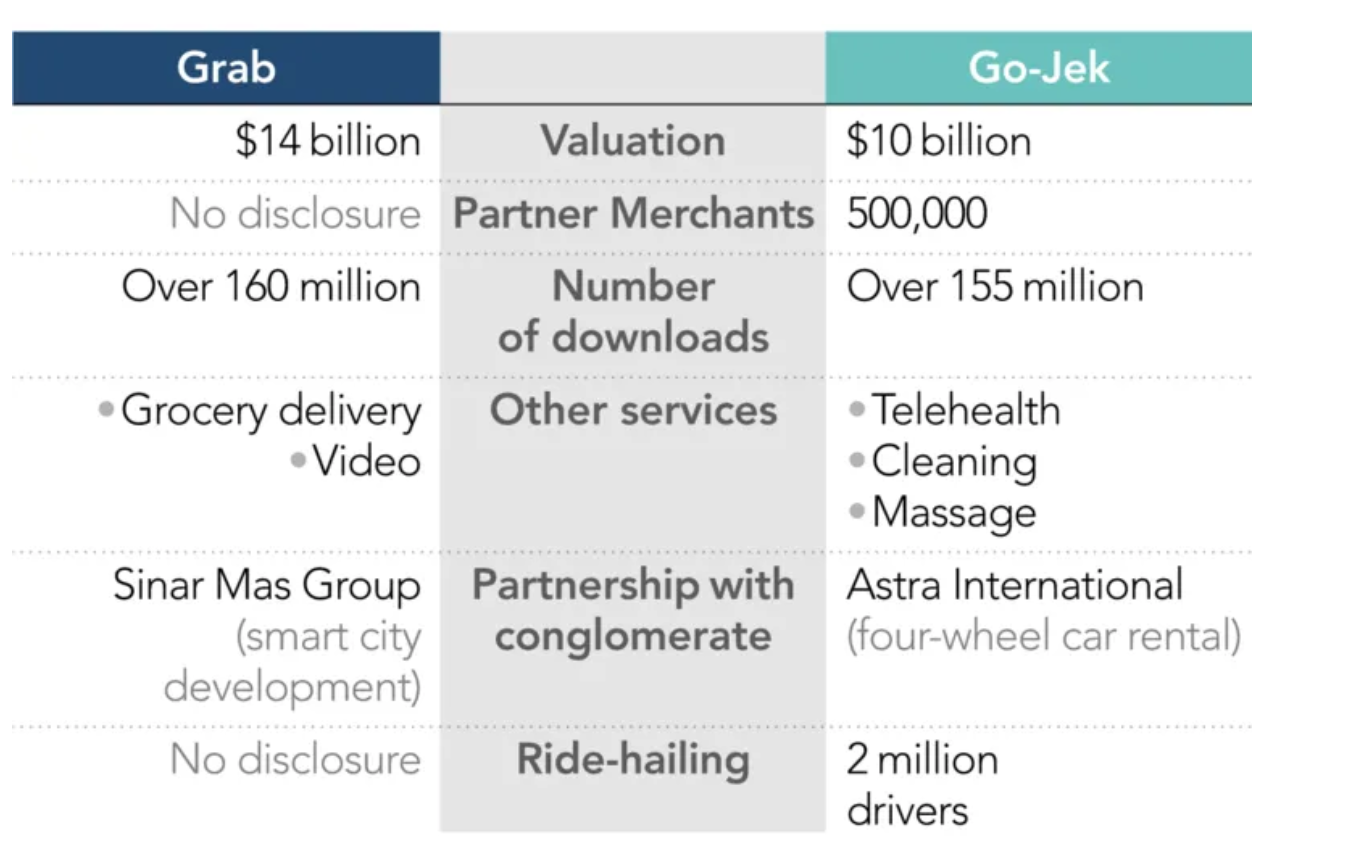

Gojek’s and Grab’s expansions have come amid the rapid digitization of Southeast Asia, which have allowed them to attract some high profile investors. Gojek counts the likes of Google and Tencent, and is valued at USD 10 billion, according to CB Insights. Grab has Microsoft, Toyota Motor and SoftBank Group, and a USD 14.3 billion valuation, according TO CB Insights, which calls itself a tech market intelligence platform.

A merger would create the world’s sixth-largest unicorn — a startup valued at over USD 1 billion — right behind the US’s Airbnb, at USD 35 billion. China’s ByteDance is the top decacorn, at USD 75 billion.

It would also create a data behemoth, one with troves of information on consumers, drivers and merchants across Southeast Asia.

Gojek claims to have 2 million drivers and over 500,000 partner merchants across the five countries it operates in. Grab has 9 million business partners, including drivers, in the eight countries it is in. Gojek and Grab apps have been downloaded tens of millions of times.

A merger would significantly increase the superapps’ chances of profitability and of a successful IPO down the road. To that end, Grab stands to benefit most from a merger.

The company will face a USD 2 billion payout to Uber if it does not go public by March 2023, but its prospects for a successful public market debut look bleak, especially since Uber’s IPO flop last May. Uber has also received investment from SoftBank.

An early investor in Grab said that it should not go public, unless it consolidates with Gojek.

But plenty of questions remain about the feasibility of a potential merger. “The complexity of this thing, it is so complex,” said a Singapore-based VC. “The [corporate] culture of Gojek and Grab is very different. You meet a Grab employee and a Gojek employee and you can really tell the difference between both of them.”

Cento Ventures’ Suckling mentioned another hurdle. “Any such merger would likely attract the attention of the multiple regulators involved,” he said. “This, of course, could prevent, delay or make such a merger very costly.”

A Gojek-Grab merger would result in a single, dominant ride hailer in many Southeast Asian countries. In Indonesia, the combined forces could create a virtual payments monopoly. The vast amount of user, driver and merchant data that a combined entity would control will likely draw the ire of regulators, especially at a time when global concerns over big tech firms are on the rise.

Grab knows well the arduous process and costs associated with defending complaints of anti-competitive behavior. In September 2018, six months after it acquired Uber’s Southeast Asian operations, Singapore’s competition watchdog fined the companies a combined 13 million Singapore dollars (USD 9.3 million). Authorities in countries like the Philippines and Vietnam have also scrutinized the deal.

“Since we don’t know the nature [or even the existence] of a deal, it’s too soon to speculate exactly what concerns would have to be addressed,” Suckling said. “But it’s fair to suppose that the regulatory side may generate obstacles that prevent a merger happening any time soon.”

Meanwhile, an official at Indonesia’s antimonopoly watchdog KPPU said that while it “cannot comment on a case that has not yet occurred” because each case needs to be studied individually, “KPPU has the duty to keep monopolistic practices from happening in Indonesia.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asian Review. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei. 36Kr is KrASIA’s parent company.