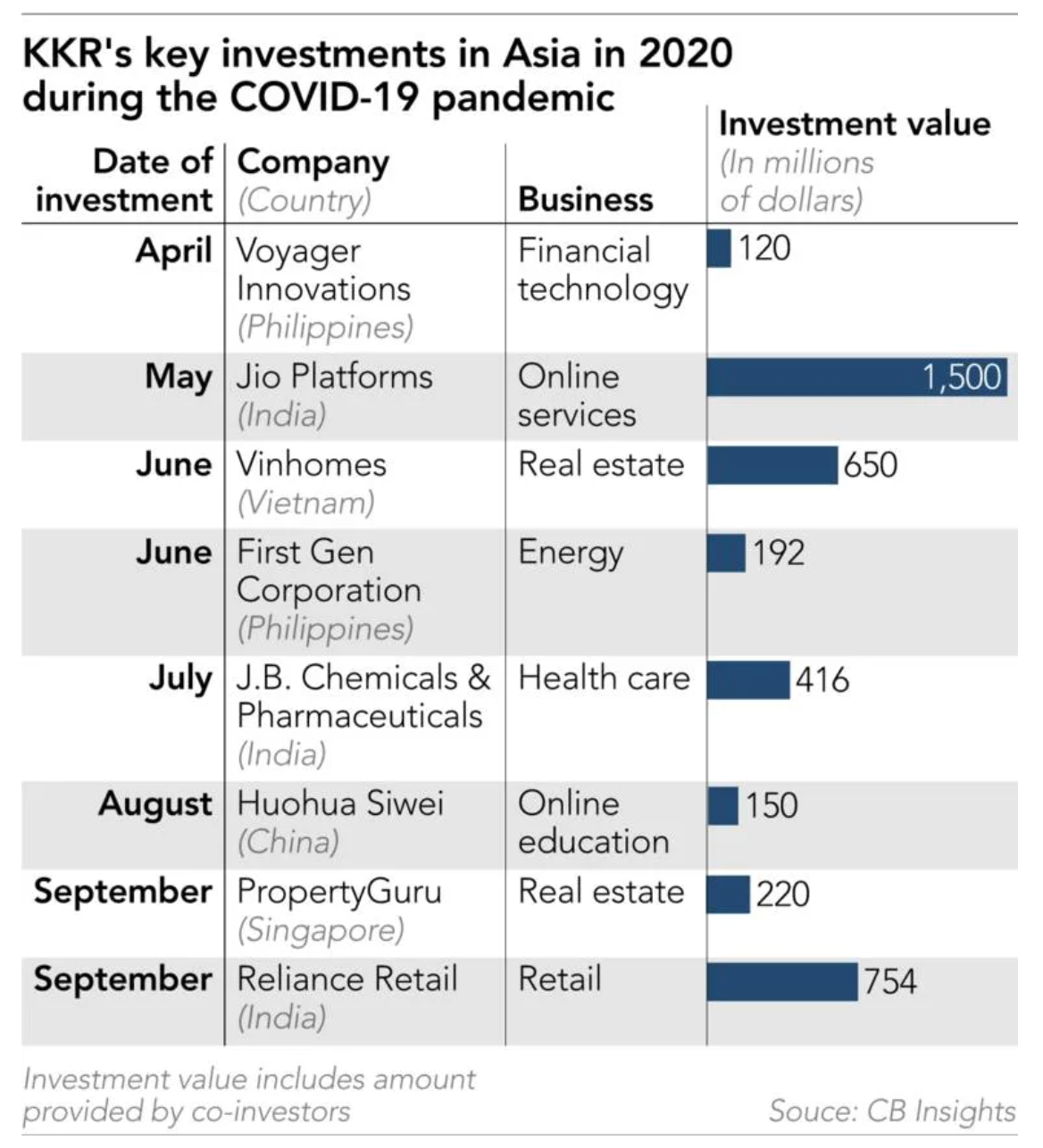

While investors and executives in Asia were still scrambling to deal with the new coronavirus outbreak in May, US investment company KKR struck its biggest deal in Asia: a USD 1.5 billion investment in Jio Platforms, a newly established digital services arm of Indian conglomerate Reliance Industries.

The deal, negotiated over Zoom calls, came in the midst of India’s nationwide lockdown. The number of infections was surging, and the economy was plunging. The reality may have spooked most investors, but KKR saw a trend that convinced it to invest in Jio at a valuation of about USD 70 billion.

“Our view was that India will eventually transform into a digital society and that all Indians will need to have access to cheap data,” Ashish Shastry, co-head of private equity for KKR Asia Pacific, said in a recent interview. “But in the second quarter, it became completely obvious that this trend was going to accelerate very fast.”

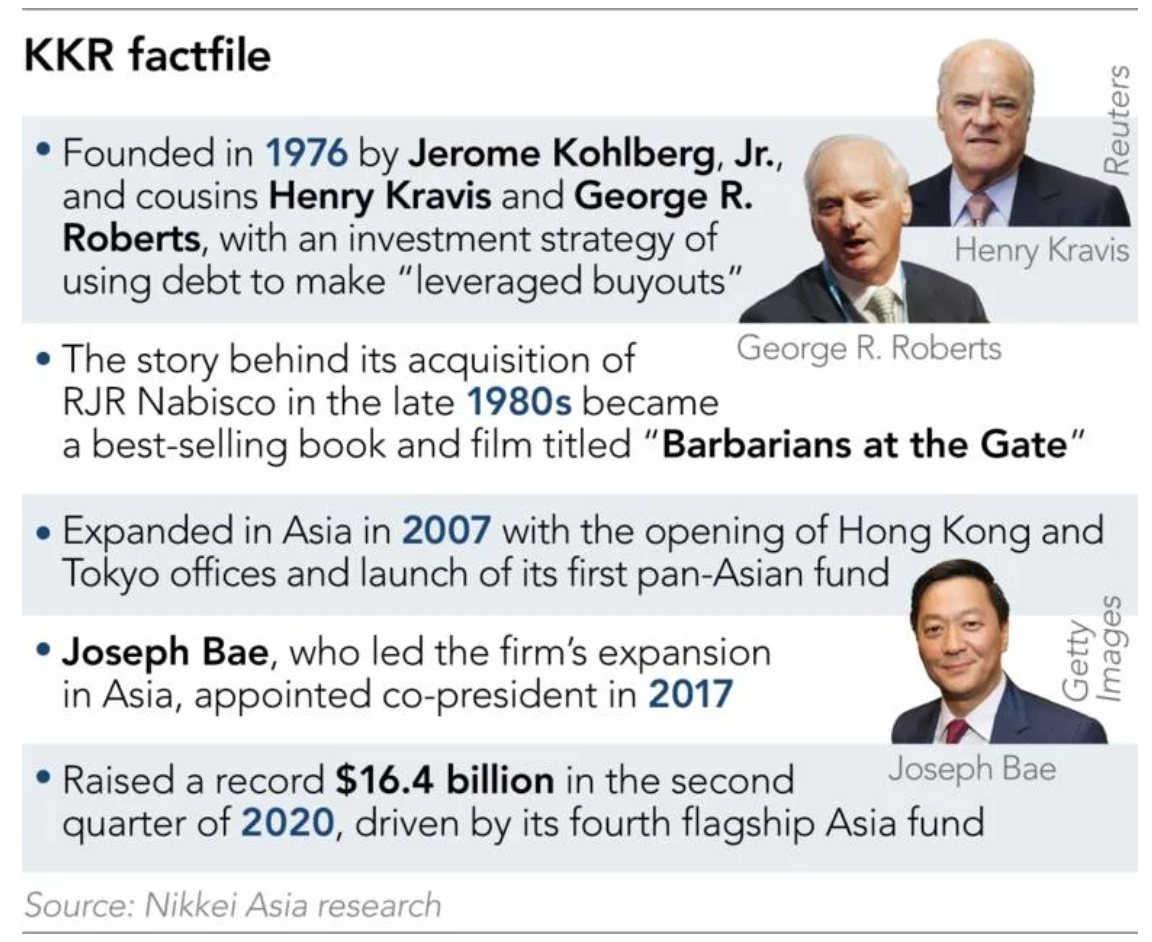

The Jio deal started a string of major bets that has turned the USD 220 billion private equity group into one of the most aggressive dealmakers in Asia.

In June, KKR led a USD 650 million investment in Vinhomes, the property arm of Vietnam’s largest conglomerate, Vingroup. The next month, it said it would take a controlling stake in Indian pharmaceutical company JB Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals for about USD 420 million. In September, it doubled down on its Jio investment by pouring another USD 750 million into Reliance Retail, the conglomerate’s retail arm that is venturing into e-commerce. In total, it has spent USD 3.7 billion in Asia since the start of the year.

If the bets turn out successful, KKR is poised to cash in the major shifts brought on by the pandemic.

Compared to the US and Europe, Asia’s emerging economies are still driven by tightly held family businesses. But most countries in the region are now contracting at a pace not seen since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. A sense of caution is prompting major family-owned businesses to reduce debt while expanding into new areas, bringing along a wave of fresh opportunities for private equity investors.

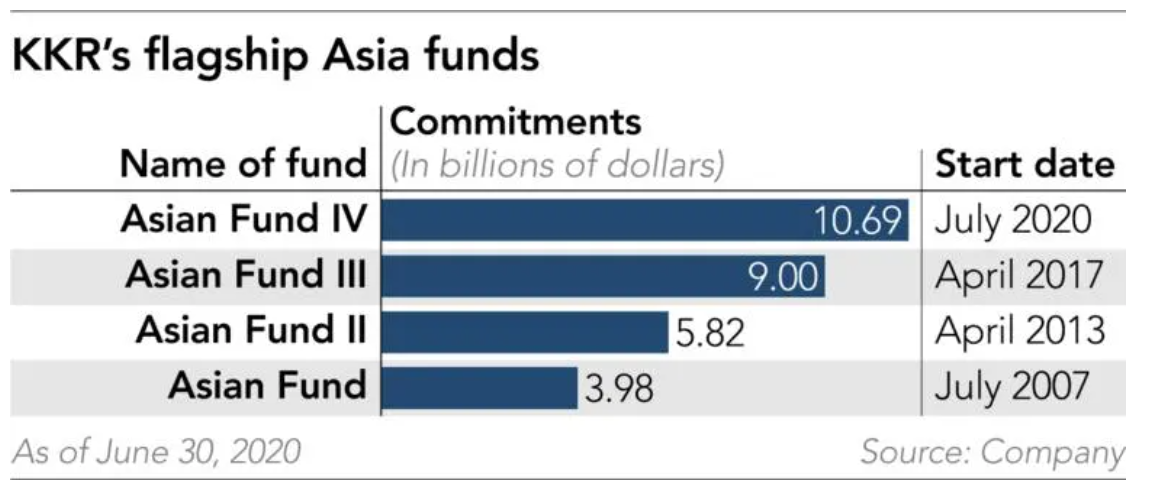

KKR has plenty of room to continue its shopping spree: Chief financial officer Robert Lewin said in an analyst call in August that it raised about USD 11 billion for its fourth pan-Asian fund, the largest investment vehicle of its kind. The fresh fundraising brought its assets under management in the region to USD 30 billion.

That figure represents about 14% of KKR’s total assets under management, but “we really believe our Asia business can be as big as our North America franchise in the coming years,” Lewin said.

With eight offices across the region, KKR has spent years nurturing relationships with Asia’s most powerful businessmen. Mukesh Ambani, Reliance’s chairman, is considered the richest man in India, and Vingroup Chairman Pham Nhat Vuong is the wealthiest in Vietnam. The network building paid off during the pandemic, when restrictions on travel and face to face meetings made it challenging to forge new connections.

Reliance, whose origins are in heavy industry, including textiles and petrochemicals, launched a mobile phone network in 2016 and quickly gobbled up nearly 400 million subscribers. Jio Platforms, the digital services arm, is building a suite of apps on top of the network, signaling its ambition to build an entire digital industry from scratch.

“This is one of those rare examples of a company that is not just a mobile company, not just a broadband company, but has a very interesting digital services play that will come in the future,” Shastry said. “Today, of course, it’s quite small, but the ideas that they have are really exciting. … This is going to be a really amazing company.”

Jio’s fundraising spree, though, also signaled an aversion to risk. Reliance used the proceeds — about USD 20 billion in total — to slash debt. Shastry said the pandemic has accelerated the need to reduce leverage among many family businesses and conglomerates, a trend that had started before the crisis, as they brace for further economic uncertainty.

KKR is also turning to past crises for how consumer behavior will change. Shastry said “nesting,” in which consumers turn cautious about traveling far and instead spend more at home, is a popular phenomenon — as it was after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the US.

On the other hand, KKR’s ballooning tech portfolio in Asia is also exposing the company to an increasingly unstable political environment.

ByteDance, one of its most high-profile investments in Asia but one where Shastry says KKR is “a very small shareholder,” has been embroiled in multiple political interventions. The US government has threatened to ban its TikTok short video app in the US, citing national security threats. TikTok said last month that it would sell 20% of its shares to Oracle and Walmart and use Oracle’s cloud service — measures to try to overcome Washington’s concerns, but Chinese state media has voiced opposition to the arrangement. The deal has yet to receive Beijing’s blessing.

In June, the Indian government banned TikTok and other Chinese apps in India after a military standoff with China along their border. Ravi Shankar Prasad, India’s information technology minister, called it “a digital strike.” Some local alternative apps have since gained in popularity.

The political clashes threaten ByteDance’s rise and are turning into a cautionary tale for tech companies with global ambitions. But KKR is taking what some may consider a counterintuitive strategy: instead of betting on companies that can go global, it is focusing on picking winners in domestic markets.

“When we talk about technological transformation and data usage, we really are going deep into each individual country to see what’s happening in that individual country,” Shastry said. “One has to be more cautious and aware today of some of the changes in the foreign investment climate, especially for technology companies. But the big tech investing opportunity is really domestic-focused companies.”

ByteDance is no exception. The company was reportedly valued at USD 75 billion in 2018 when KKR invested, making it one of the world’s most highly valued private tech companies. While some observers attribute the high valuation to its rapid growth overseas, the figures may also stack up if ByteDance becomes a Chinese internet giant. Alibaba Group Holding is worth more than USD 800 billion, and Tencent Holdings more than USD 600 billion. But both still generate most of their profits from inside China.

“BAT has been Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent,” Shastry said, referring to the acronym for China’s biggest technology companies. “We think there is now an additional BAT, of ByteDance, Alibaba, and Tencent.”

Other tech investments across Asia are also domestically focused. In China, these include Huohua Siwei, an education startup, and Xingsheng, a distribution system for groceries. Even Gojek, the Indonesian on-demand app operator, is mostly focused on its home market despite its expansion into other Southeast Asian markets, Shastry said.

Picking winners is becoming even more crucial as rival fund managers look to expand in Asia. Online education companies in China have been raking in capital amid the pandemic, including from KKR’s rivals. Prominent venture capital firms such as Sequoia that generally invest in the early stages of a startup have raised billions of dollars in the region to continue investing in later stages.

While the strategy of trying to find local champions may help shield KKR from political turmoil, the company may also miss out if companies continue to go global.

“We may temporarily go back to a risk-off mindset, which usually means back to core, which usually means a bias to local,” said Claudia Zeisberger, a Singapore-based professor of entrepreneurship at Insead business school. “But I don’t think it’s going to be sustainable. A global world will remain a global world.”

A booming IPO market for tech companies in the U.S. is also posing a challenge for private market investors. A string of U.S. tech companies recently went public at eye-popping valuations, drawing comparisons to the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s.

The prospects of a high valuation may prompt a founder to raise capital through an IPO instead of private investors.

KKR is cautious over whether the stock market rally will last. It believes the economic fallout from COVID will last for years, and that the massive government stimulus packages may eventually run out. Henry H. McVey, KKR’s head of global macro & asset allocation, has said he expects a “square root-shaped recovery” with US GDP possibly not returning to pre-COVID levels until early 2022. The forecast suggests that government stimulus — which is propping up economies and stock markets — will eventually lose steam.

“When you have so much government stimulus and interest rates are so low, it really does boost the public markets,” Shastry said. “But at the same time, there are many companies that are facing challenges that won’t have access to those public markets. I think that’s why private equity will end up playing an important role.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.