As cities worldwide went into lockdown last March, most businesses were forced to shut their doors and forgo revenues for a few tough weeks. You would think restaurant owners had an easier time, given they worked with food aggregators to power the on-demand food economy. You would be wrong.

Let me explain. Since its inception, the “food economy” hasn’t been good to any of its stakeholders:

Restaurants complain of the astronomically high commission rates (up to 35%) paid to food aggregators, feeling stuck with no clear alternatives.

Customers often complain of inconsistent quality and delays.

Food aggregators (and their investors) continue to lose money, and none have turned a penny since inception. Unprofitable growth-at-all-cost was acceptable in the past, but investors have grown impatient, asking their ventures for a clear path towards profitability.

Drivers and riders complain about low pay and limited social protection. (This is mostly in the US, where riders are considered as contractors and in many cases get paid less than minimum wage.)

These challenges have led to rising tensions between the stakeholders, which triggered three key events, or rather turning points, in May and June last year: Uber Eats decided to close its operations in Middle Eastern markets.

Regional restaurants partnered with ChatFood, Taker, Zyda, Blink, and many other similar platforms to start their commission-free websites allowing customers to order directly from these websites.

Mohamad Alabbar, the founder of Noon, attacked food aggregators and promised to bring to the market a new service that would greatly reduce commissions.

Last week, Alabbar kept his promise, introducing Noon Food, a new food delivery service, that limits its commission to 15% and challenged others to follow suit. In parallel, Careem, the region’s ride-hailing company recently acquired by Uber, removed its variable commission structure, asking restaurants to pay a fixed monthly fee instead and cover delivery expenses.

But how can Noon make money in such a tough industry, while others with twice the commission can’t?

Noon can’t win following the same approach of current players, but if it changes how the game is played, the results could turn the industry’s tough economics around.

Unit economics in food delivery

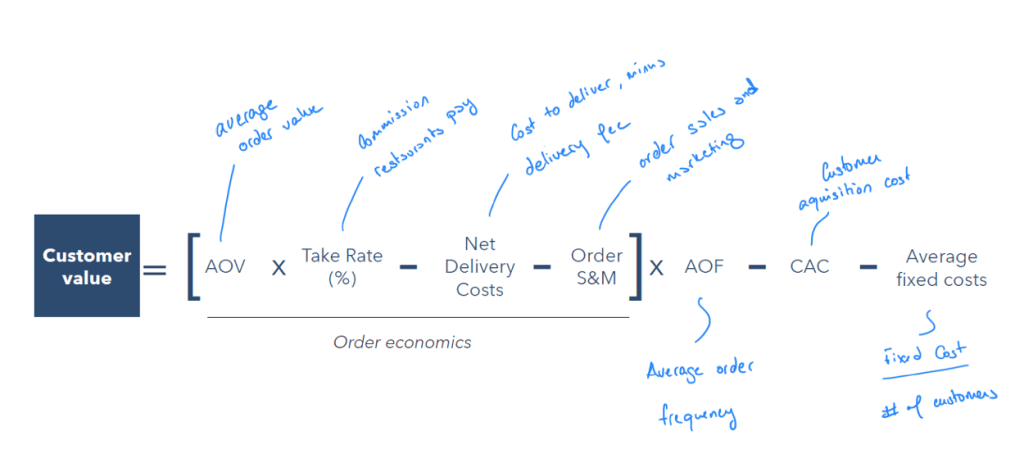

Like e-commerce, unit economics in food delivery can be broken down into a “simple” formula, where seven metrics determine a customer’s net value.

AOV refers to the average order value, which in general is lower than other e-commerce categories, given most consumers order relatively cheap fast food items.

Take rate is the commission restaurants pay to food aggregators.

Net delivery cost is the cost to deliver the food to the consumer minus whatever fee the consumer pays.

Order S&M cost refers to sales and marketing costs on each repeat order (covering payment fees and follow-on marketing expenses).

The above elements constitute the economics of an individual order. If you don’t make money at this stage, I have terrible news for you!

AOF refers to the average order frequency, which estimates how many times a consumer orders over the customer lifetime.

CAC is customer acquisition cost and refers to the marketing expense an aggregator incurs to get a customer to place their first order.

Average fixed costs refer to the general and administrative costs (salaries, tech infrastructure, office) and research & development expenses, divided by the total number of customers.

Let’s consider an example:

Assuming an AOV of AED 60, the food aggregators receive AED 18 (30% of AOV = take rate). It costs AED 20 to deliver the food, and the customer is charged AED 7, so the net delivery cost becomes AED 13. It also costs AED 3 for sales and marketing expenses per order.

As a result, the food aggregators keep AED 2 in order contribution out of each order. If a customer orders 50 times a year on average, they contribute AED 100 per year. At an average fixed cost per customer of AED 60, each customer generates AED 40 a year (before accounting for CAC).

Assuming a five-year lifetime, a customer would be worth AED 200 for the delivery aggregator. As long as they’re spending less than that to acquire them (let’s say AED 30), they’re making money.

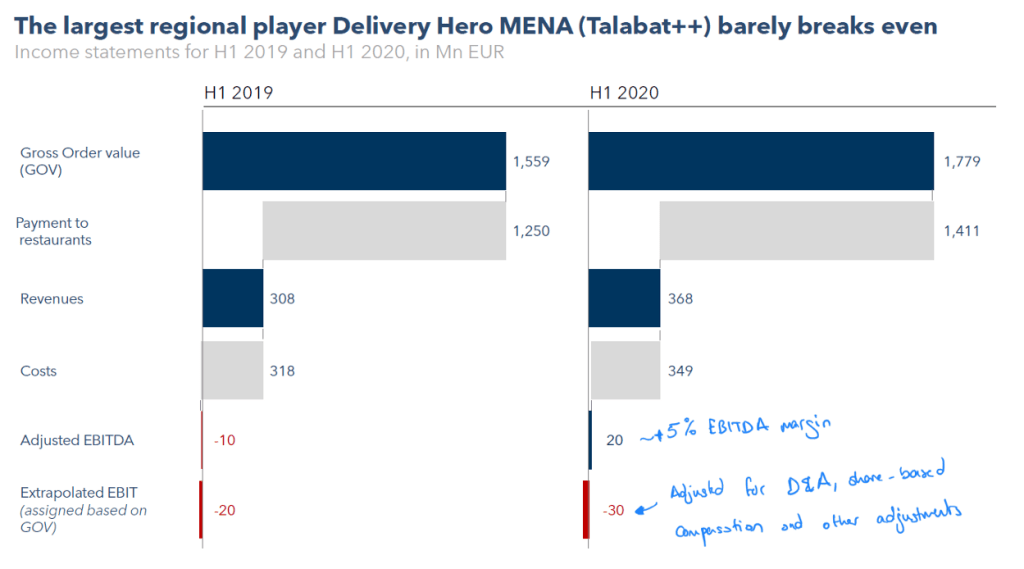

Unfortunately, this example is simplistic and theoretical. Reality is different, and even the most efficient player in our region, Delivery Hero/Talabat, struggles to make money.

The difficulty of making money in food delivery

Three core issues are at the heart of why most players in the industry suffer:

(1) High delivery costs resulting from the “point to point” delivery model and low utilization. Unlike other delivery businesses, food delivery requires a driver to pick up food from one supplier and deliver it to one customer, making a trip per order. (In e-commerce, a driver can pick up from one warehouse and deliver to multiple customers.) Adding to the complexity, food delivery has distinct peak times (lunch, dinner), forcing drivers to go unutilized for most of the day.

(2) High competitive pressures in the space (Deliveroo, Talabat, Zomato, Careem Now, and Noon Food) and low switching costs (it takes two minutes to download an app and save your payment information and location) mean that aggregators need to spend on marketing and discounts to keep customers on their platforms, otherwise risking a lower average order frequency.

(3) Low average order values in food make profitability sensitive to simple leakages / operational issues. If delivery cost increases from AED 20 to 21 in our example above, a customer’s net value drops by 75% (from AED 200 to AED 50). If AOF drops by 20%, a customer’s net value drops by 50% (from AED 200 to AED 50).

Noon’s approach

Noon launched in 2017 as a Middle Eastern e-commerce platform, providing customers with an assortment of products to buy online. The company expanded towards new business lines, launching online grocery delivery in 2020 (both scheduled through Noon Daily and on-demand through NowNow) and food delivery (through Noon Food) this year.

Initially launched with a vision of becoming the “Middle East’s Amazon,” Alabbar quickly realized that competing with Amazon in a game they practically invented is a losing proposition. This drove the Noon leadership team to pull off one of the most impressive strategic pivots the region has ever seen: Noon will no longer be the region’s Amazon, it will be the region’s on-demand FedEx.

In doing so, I believe the company repositioned itself as a logistics company, increasing the breadth of its playing field across various verticals and selectively integrating backward into areas it deems attractive—with grocery dark stores, product white labels, and ghost kitchens that I’m confident will come very soon. With this positioning, Noon aspires to resolve food delivery’s core problems, namely low driver utilization and low customer loyalty.

Logistics-first approach

Noon is best positioned among all food delivery platforms to maximize its drivers’ utilization by using them across its business lines. Here’s a simplistic visualization of how a Noon driver might split their day:

- Peak food times (breakfast, lunch, dinner): Most drivers focus on on-demand delivery (food and groceries) and are strategically located near restaurants with the highest order volume.

- Non-peak times: A larger portion of drivers report to Noon’s warehouses, where they help deliver parcels to customers that ordered on Noon.com and groceries to people that ordered on Noon Daily.

Such an approach would improve overall utilization and drop delivery costs, making the order economics more attractive and compensating for the lower take rates.

A large ecosystem

Noon’s large ecosystem means that the company can divide its marketing spend on a larger set of businesses and can offer its customers a multi-faceted loyalty program that encourages them to stay on their platform. Think Amazon Prime with a twist.

Cue Noon VIP, the loyalty program the company launched in late 2020, rewarding loyal customers with discounts, faster delivery, and other perks. The product is a loss leader for the company, but similar to Amazon Prime, it aims to maintain customer loyalty and increase mental switching costs.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Noon VIP customers start receiving special offers and lower delivery fees to order from Noon Food, which would ultimately lead to a higher AOF.

Beyond delivery

As it grows, I suspect Noon Food will offer its partner restaurants more services, deepening its relationship with them and generating additional profits. These services range from promotion planning all the way to consulting services to help them optimize operational decisions, such as the locations for mobile kitchens, using the data it has.

Even though Noon’s strategy theoretically works and would’ve looked great in a consulting strategy deck, executing it will be much harder. People hate consultants because they overuse words like “leverage” and “synergies,” often advising their clients to “leverage their assets across business lines and create synergies leading to cost savings.” Anyone who has led a business knows that capturing such synergies is extremely complex, especially when human capital is involved.

Either way, as one of the few successful regional technology companies, I am rooting for them to succeed and figure this out!

What’s next?

As competition intensifies and the level of technological and business model innovation rises in this space, the future looks very exciting, especially for consumers. Here’s how I believe various stakeholders would fare:

Customers will be net winners, heavily benefiting from increased competition in this space. They’ll be able to recoup great offers as different players entice them to use their platforms—and they’ll do so easily given the low switching costs. They’ll also benefit from reduced take rates, which will partly flow to them as discounts.

Restaurants will initially benefit, given the low take rates that they receive. Yet, similar to all businesses that outsource their distribution, restaurants will eventually pay the price as aggregators, like Noon Food, use the data they generate to integrate backward and open up their own virtual restaurants to deliver the most lucrative products themselves. I discussed this concept in great detail here.

Food aggregators will have a tougher time competing now that a new player with deep pockets is in town. At this stage, it’s important for them to focus on their individual niches, i.e. Deliveroo on higher-value customers, and look to add value to their restaurants in different ways. Even though Alabbar invited them all to reduce their commission, they absolutely should not, as they can’t play the same game that Noon is playing. Not yet, at least.

This article was written by Imad El Fay. It was first published by MENAbytes.