Southeast Asia’s tech giants are in an intensifying battle with large conventional banks over the region’s burgeoning digital banking services.

As “superapp” providers such as GoTo and Grab look to bolt banking onto their expanding range of services, and existing players use the region as a sandbox for digital experimentation, long neglected rural populations may soon have access to some of the most technologically advanced financial services in the world.

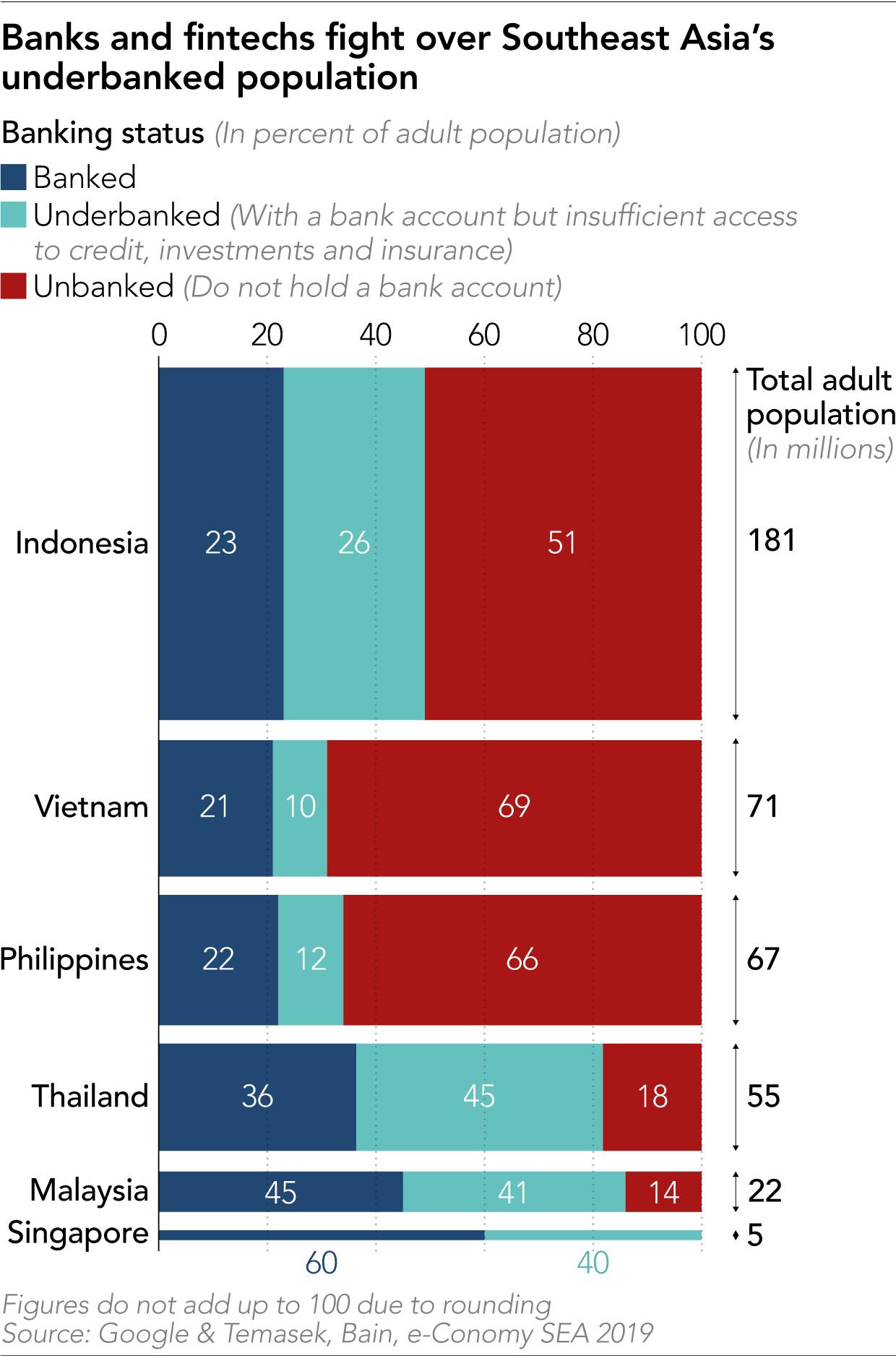

According to research conducted by Google, Temasek Holdings and Bain & Co., about half of Southeast Asia’s nearly 400 million adults do not have a bank account. Over 90 million more are “underbanked”: They hold a bank account but lack sufficient access to investment products, insurance or credit. Millions of small and medium-size enterprises also face significant funding gaps, the research states.

The problem is particularly acute in Indonesia, where more than 70% of adults—about 140 million people—are “unbanked” or underbanked, in part because of the cost of offering traditional services. Building physical banking networks, such as branches and ATMs, to cover an archipelago of 17,000 islands to serve mostly low-income people has proved nearly impossible.

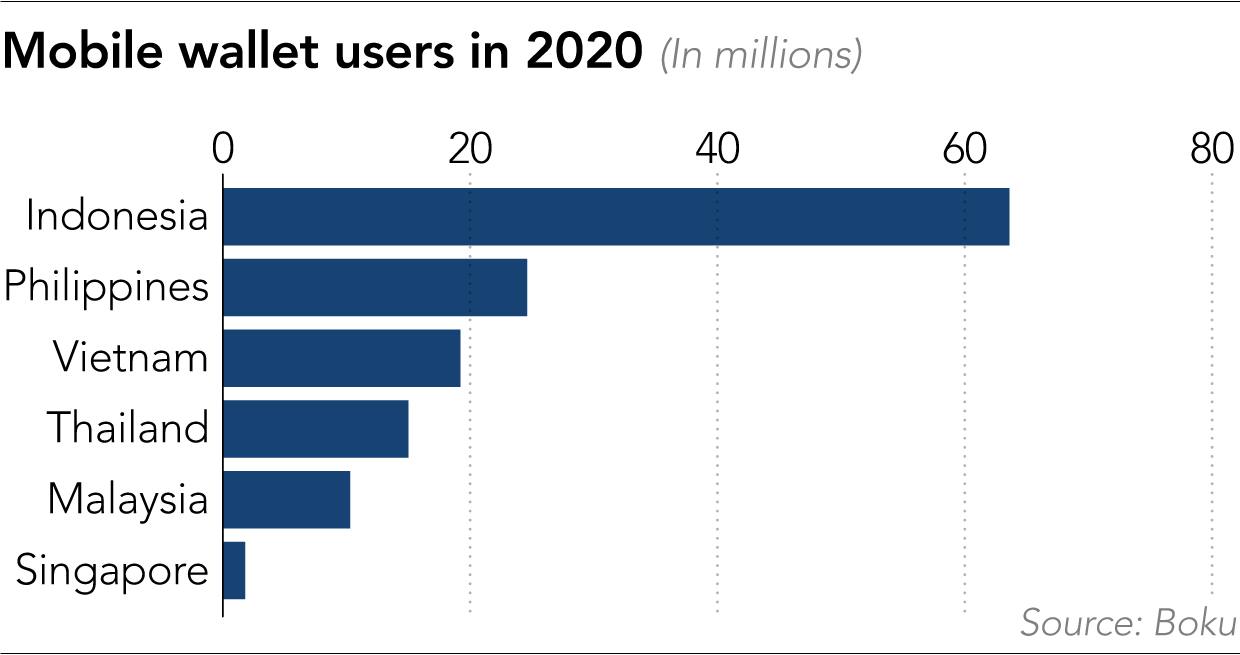

But rapid smartphone adoption in the country is changing the landscape. GoTo, Indonesia’s largest tech conglomerate, will soon offer fully integrated banking services with its local partner, Bank Jago, competing directly with digital offerings from incumbent banks, including Singapore’s DBS Group Holdings and United Overseas Bank (UOB).

For GoTo, formed through the merger of two of Indonesia’s most prominent tech companies, ride-hailing provider Gojek and e-commerce giant Tokopedia, the expansion is a natural extension of services already offered through its superapp.

Its e-wallet service, GoPay, allows customers to make cash deposits at convenience stores and use the app to make purchases, access credit through “buy now, pay later” schemes, and even make micro-investments in US index funds and gold.

Gojek bought 22% of Bank Jago, a local bank, late last year. Together they plan to offer a full range of banking services. GoPay customers in Indonesia will soon start receiving a message saying, “Open a Bank Jago account,” which they can easily set up directly from the app. Cash that is already in their e-wallets can be used as their first deposit. Customers will immediately receive a Visa debit card and access to investment options. Perks include discounts on products sold on Tokopedia.

The service looks like a combination of Amazon.com, Robinhood, PayPal, and Citibank, all in one app. The company’s ultimate aim “is to be the core of the way in which users manage their finances,” said Budi Gandasoebrata, GoPay’s managing director.

GoTo also plans to offer similar banking services to small and midsize businesses that use Gojek and Tokopedia’s services. “That’s where we see [the service], hopefully, within next five years,” said Gandasoebrata.

It is not hard to see why Indonesia has become the focus of innovation and competition in banking. It is the region’s most populous nation and, with half of the population aged 30 or younger, one of the most digitally savvy. According to Boston Consulting Group, it boasted the second-highest rate of e-payments in Southeast Asia, next to Singapore, as of the end of 2019. The number of Indonesia’s middle-class and affluent consumers is expected to grow by up to 130% between 2019 and 2024. Over the same period, banking revenue is forecast to rise from USD 47 billion to USD 77 billion.

Early this year, Singapore-based internet giant Sea, which provides e-commerce and e-wallet services that compete directly with GoTo, acquired majority control of a small Indonesian lender called Bank Kesejahteraan Ekonomi, which it renamed SeaBank. Akulaku, an Indonesian fintech startup backed by China’s Ant Group, also joined the fray, becoming the largest shareholder in Bank Yudha Bhakti, which later changed its name to Bank Neo Commerce.

However, large incumbent banks in Southeast Asia, such as Singapore’s DBS and UOB, had a head start in providing digital banking services in the region.

UOB launched digital bank TMRW in Thailand in 2019, and in Indonesia the following year. The service has already amassed more than 400,000 users.

Janet Young, UOB’s head of group channels and digitization, said the company is acutely aware of the intensifying competition from tech giants. “We see them as competitors because they own the ecosystem … but have less regulatory requirements because they are not banks. Running a bank with all the compliance, all the regulatory guidelines—managing the balance sheet is different from just being an e-wallet,” she said.

Unlike the new entrants, Young said TMRW is designed to serve the region’s young professionals, such as those “who have graduated from college and got a job, or someone who has worked for few years, and digitally savvy customers who are primarily mobile first.”

Young stressed that UOB is not using its digital banking service as a “defensive move” to fend off the tech giants. Instead, she says, “we use TMRW as a [customer] acquisition strategy. It is a lower-cost acquisition for us, compared to the brick-and-mortar [business]. A digital bank is a lot more scalable and cost-effective.”

UOB is also using TMRW as a laboratory for innovation, which it believes will strengthen its core banking services in developed markets such as Singapore. It announced last month that it would invest up to SGD 500 million (USD 371 million) in digital services and to unify its digital bank capabilities from TMRW and its main banking apps used in countries such as Singapore. The bank said that it “seeks to double the retail customers it serves digitally to more than 7 million customers across ASEAN by 2026.”

“Consumer behavior is gravitating to digital. If we are not digital, we will miss that ability to serve them,” said Young.

The battle between banks and fintech companies is also set to heat up in UOB’s home market. Both Sea and Singapore-based superapp provider Grab plan to roll out digital banking services in the city-state early next year. Analysts say the combatants bring powerful but differing strengths to the fight.

“Incumbent financial institutions in digital banking services have the advantage of obtaining financing for investments, as they have more collateral and better reputations, and relations with existing creditors and investors,” said Gavin Yue, a research consultant with Kapronasia, a fintech-focused consulting firm.

“They also have better access to internal funds, which implies that they are better capitalized. This could have an impact on, for example, marketing initiatives, pricing, and acquisitions.”

But “on the flip side, digital upstarts have more flexible data infrastructures, unlike incumbent institutions that have to grapple with layers of legacy technology, which harms data analysis and subsequently the products, services, and overall experience that [they] can provide to consumers,” Yue said.

“The entrance of tech upstarts such Grab or Sea is an ambitious one, but at the same time calculated. Largely driven by the pandemic, consumers are increasingly looking for digital channels to complement almost all aspects of their lifestyle.”

The fintech revolution in Southeast Asia is forcing other players in the financial ecosystem, such as Visa and Mastercard, to adapt.

“In any given year, we’re partnering with 50 to 60 fintech companies in the Asia-Pacific,” said Matthew Wood, who oversees Visa’s digital and fintech partnerships in the region. Tobias Puehse, vice president for innovation and customer solutions with Mastercard’s Asia-Pacific business, said that “leapfrogging markets” — those whose customers bypass old banking structures and embrace mobile apps and digital payments first — “will always give us a glimpse of consumer behavior.”

Both payments companies are competing vigorously in the region to extend their partnerships beyond traditional banks. Visa invested in Gojek in 2019 and Mastercard is a partner of Grab. According to Visa, fewer than half of consumers in Southeast Asia see cash as their preferred payment method. “Ultimately, our objective is to kill cash, and fintech can and will be a big driver of moving commerce in Southeast Asia to become more and more digital,” said Wood.

The string of computer glitches faced this year by Japanese bank Mizuho, including one that brought most of its ATMs to a temporary halt, is a reminder of the difficulty of upgrading legacy systems, while closing brick-and-mortar branches in established markets such as the U.S. incurs short-term restructuring costs, even if it saves money in the long run.

But new and old financial players in Southeast Asia are showing that they can build an app-only digital banking infrastructure, nearly from scratch, in countries like Indonesia — a textbook example of a leapfrog. As Kapronasia’s Yue puts it: “Certainly the competition from new players will mean consumers stand to benefit.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.