Online shopping festivals like mid-year sales that take place in June and mid-November’s Singles’ Day bonanza have been organized for Chinese consumers for more than a decade. They’re like Black Friday, Cyber Monday, or Raya and Ramadan shopping, where shoppers make a beeline for deals and discounts.

Yet, there are snags. The shopping experience isn’t always satisfactory, and consumers have found themselves in increasingly frequent encounters with misleading and confusing terms and conditions.

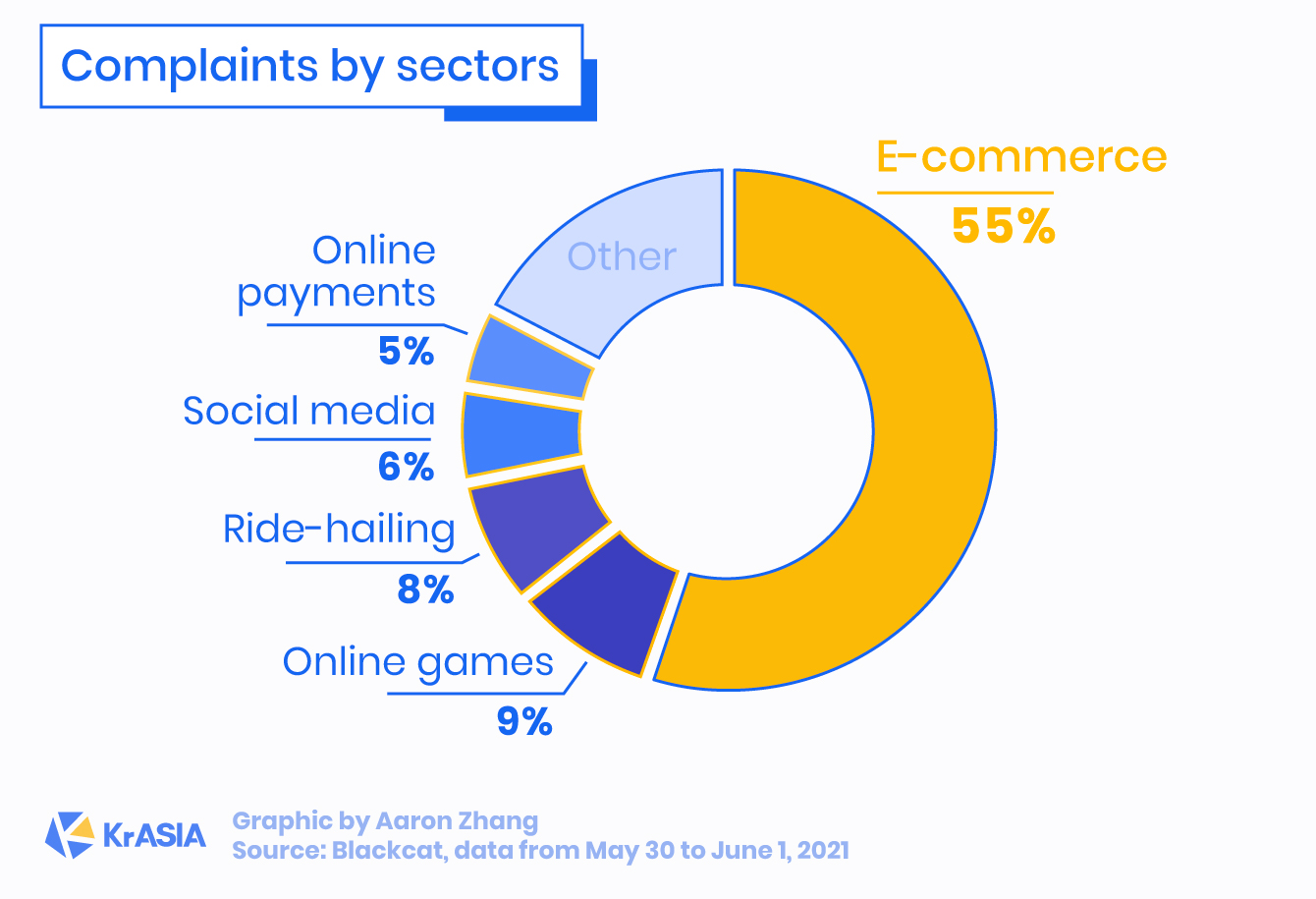

This year’s mid-year online sales gala in China started on May 24 for both JD.com and Taobao, the two most popular e-commerce sites in the country. KrASIA combed through 988 grievances filed with the third-party consumer complaints site Blackcat between May 30 and June 1 to uncover the real sentiment behind glossy sales promotions and record-breaking transaction numbers.

E-commerce receives the most complaints

Blackcat logs consumer objections of all types. E-commerce platforms are frequent targets of ire—55% of the records examined by KrASIA that relate to the internet economy name China’s online marketplaces as offenders, with Pinduoduo, Alibaba’s Taobao, and JD.com receiving the highest volume of complaints on the site.

Over-complicated terms and conditions for sales

Complaints related to product pricing are the most common. Buyers found it difficult to navigate the platforms’ mercurial and byzantine discount rules, or felt deceived by marketing tactics that made sales look more generous than they actually were.

Dark patterns are common: online marketplaces pack their sites with banners showing 618-specific discount packages, which include red packet cash handouts, general discounts, coupons, shipping subsidies, and price reductions for members.

However, claiming these perks can be an uphill battle. The rules are at times opaque, and include many prerequisites and restrictions—too many to reasonably expect anyone to go through line by line. Customers are left to crunch the numbers on their own to figure out exactly how much they’re about to pay for the items in their checkout basket.

Here’s an example of how people felt conned. Some merchants said they would offer discounts to anyone who shells out for VIP memberships, yet after customers paid for this perk, products were not available to them:

Tmall’s Apple flagship store launched a “618” event allowing Tmall’s “88VIP” users to receive RMB 400 (USD 63) off for the iPhone 12 and other products from June 1 onward. Subsequently, many consumers spent RMB 88 (USD 14) for the “88VIP” label. However, on the morning of June 1, iPhone12 stock was sold out in a matter of seconds. At 6:00 p.m. on the next day, I found that it was back in stock, so I tried to buy one, but Tmall kept showing me that the purchase failed. In the meantime, colleagues who didn’t have “88VIIP” status could place orders normally.

On JD.com, China’s third-largest online shopping site, VIP members were locked out of many “618” sales campaigns:

Since the beginning of the “618” sales, I have not been able to receive any coupons or buy from many brands. The customer service of JD has not done anything to solve this, so I cannot enjoy the discounts provided by the platform. I would like a refund for the RMB 148 (USD 23) I spent on the membership and recoup the right to receive coupons.

Another common tactic deployed by sellers is a “price guarantee,” which in theory protects customers from having to pay higher rates if an item’s price goes up after a sale ends. Typically, merchants say this guarantee is valid for at least seven days, depending on the time frame specified for each store. But consumers have frequently found themselves paying more than they should. What’s more, some consumers were not informed of the terms of coverage until after they filed complaints with customer service:

I bought some medicine on June 1, the price was RMB 1,377 (USD 215)! On June 5, I found out that the price of the same product is only RMB 1,342 (USD 210)! I contacted customer service for a refund of the price difference, but they rejected me! Only then was I informed that the so-called “618 price guarantee” meant that the price was not insured until after June 21!

This has been a persistent problem. The China Consumers Association (CCA) wrote about the issue in a report that was released in 2017. Complaints about faulty “price guarantees” accounted for 13% of the Blackcat records related to e-commerce that KrASIA examined.

Fake price reductions

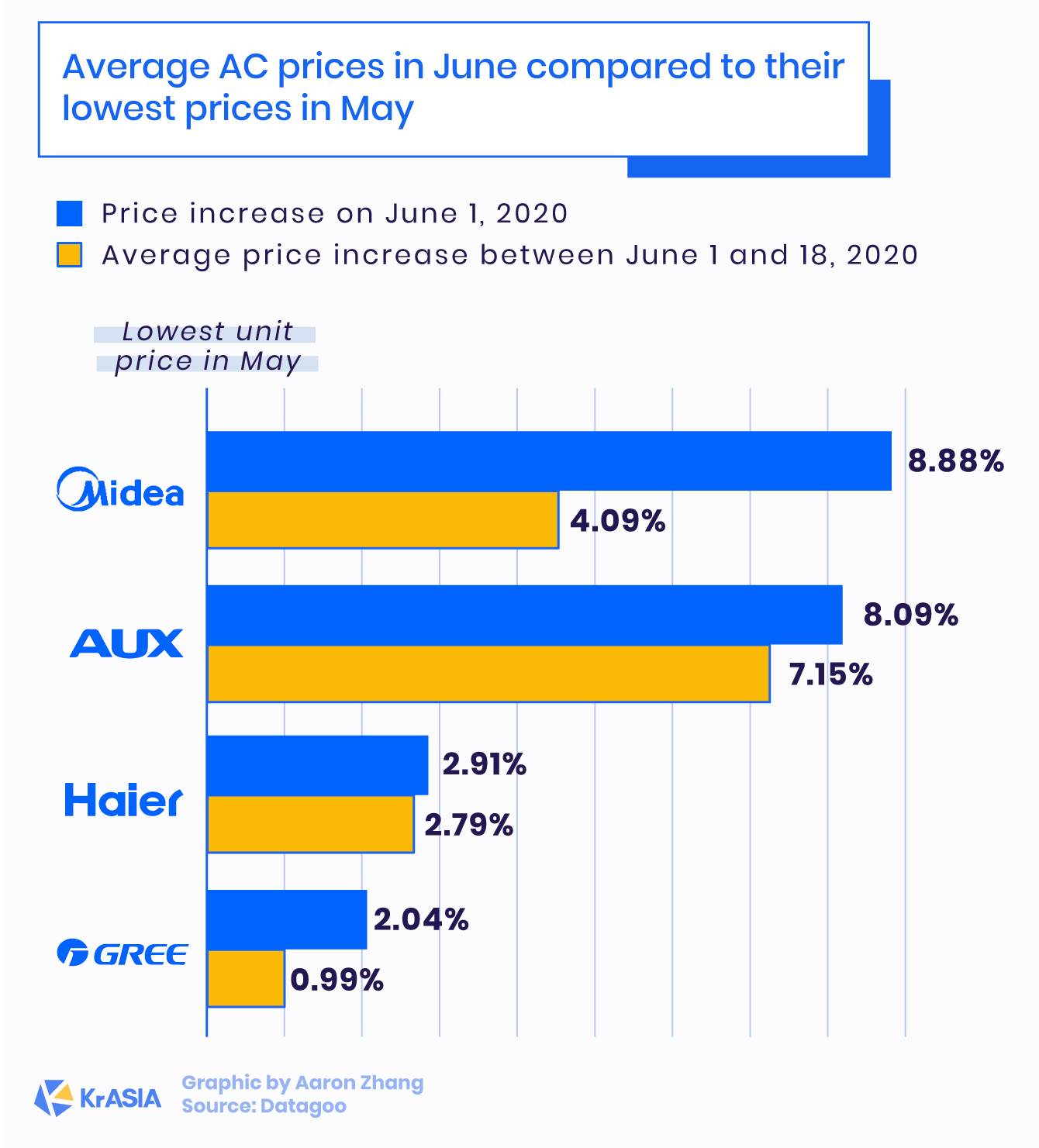

Some merchants raise the prices of their products ahead of major sales festivals, then mark them back to their original levels to give off the appearance of hefty discounts during sitewide mega sales. Chinese media outlet Time News tracked the price changes of air conditioners from four different major brands in 2020. All of their prices increased before the “618” festival last year.

In its 2017 report, the CCA found that 78.1% of the items sold during so-called annual sales can be bought at the same or lower prices before or after the festival.

Endless text harassment

Some merchants take spamming to a whole new level. Ahead of major sales festivals, sellers may utilize the phone numbers they collected for previous orders and initiate text message bombardments. “Even though consumers don’t want to spend money, they would still get this type of text message harassment every month,” said the CCA in its 2020 report regarding the “618” shopping festival.

E-commerce companies are doing more business than ever

Chinese consumers have been shopping online for years, and many are familiar with the tactics that are mentioned above. Even though customers are at times deceived or harassed, e-commerce companies are recording consistent growth.

Last year, Alibaba and JD.com generated a total gross merchandise volume of USD 137 billion from their “618” shopping campaigns. For Singles’ Day in November, the two companies raked in a combined USD 115.1 billion.

On the opening day of this year’s “618” online shopping festival, the stock price of Pinduoduo shot up by 11.58%, while Alibaba and JD.com’s increased 2.58% and 5.94%, respectively. China’s two biggest shopping festivals, November’s Singles’ Day and 618, have become the major driving forces of these companies’ GMV and revenue growth in the second and fourth quarters.

Take JD.com as an example. In Q1 2020, the Beijing-based firm’s revenues were USD 22.8 billion. For the next three months, when it hosted its signature 618 sales event, revenues rose to USD 31.4 billion.

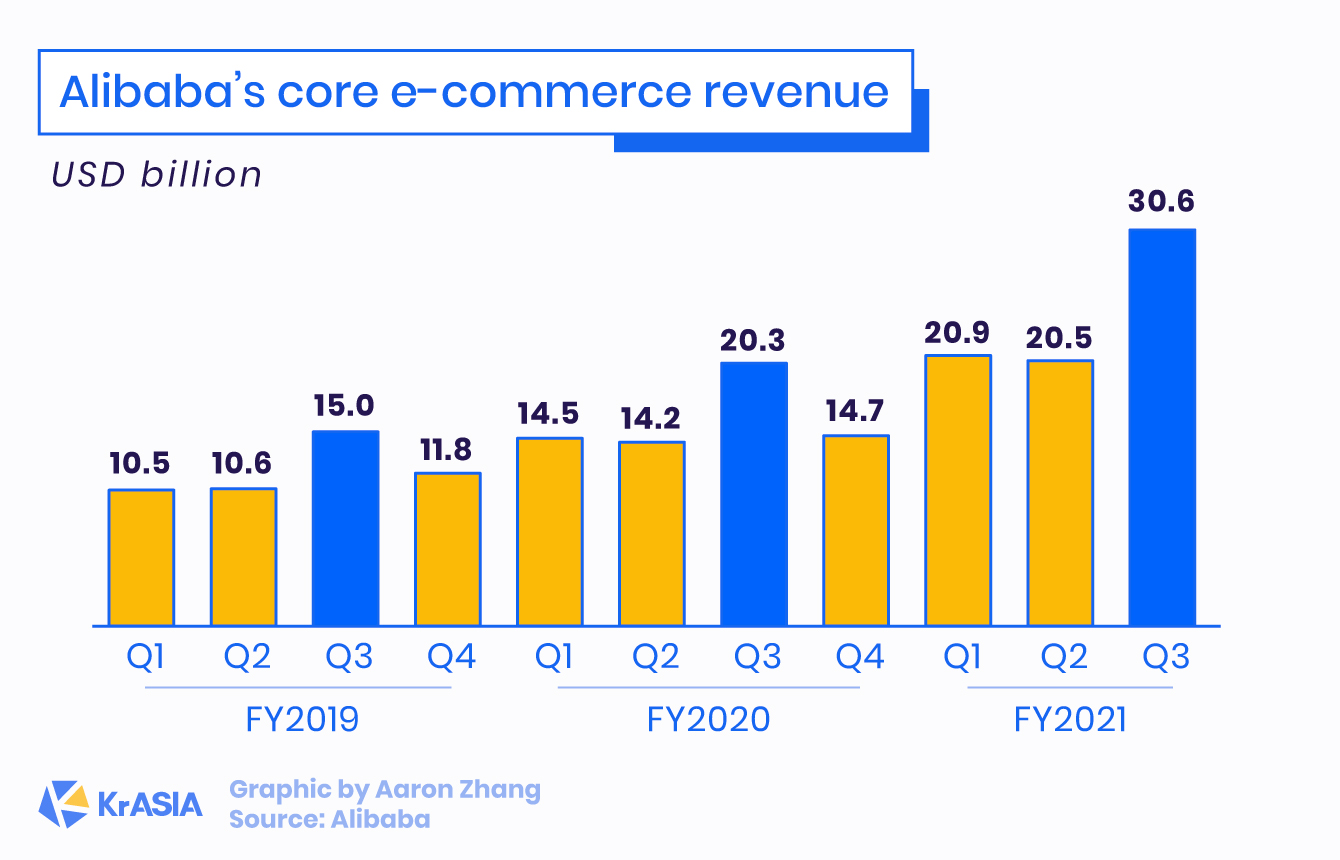

As for Alibaba, the quarter when Singles’ Day takes place each year consistently generates the highest core commerce revenue for the year.