Car-leasing startup Smove was startlingly popular and easy to use, even in expensive and rule-bound Singapore. With the tap of a prepaid card, anyone could jump in a vehicle off the street, start it with a push of a button and drive for as little as USD 1 per quarter hour.

As ride-hailing giants Uber Technologies and Grab expanded through Southeast Asia, rapidly and seemingly unstoppably, founder Tom Lokenvitz thought he’d found a way to ride on their coattails. By 2015 he’d scored a deal supplying cars to Uber’s drivers — which he scrambled to fill by taking out long leases to increase his fleet numbers. Meanwhile, Grab and Uber worked the upstart’s playbook, offering deep discounts and subsidizing rides in an intensifying battle for market share in the region.

For a while, Lokenvitz’s gamble succeeded. In the six months after the deal with Uber was struck, Smove Systems thrived. Its fleet expanded tenfold, head count tripled and, at one point, it was the largest business of its kind in Asia.

Then came the bombshell: Uber’s abrupt 2018 exit from Southeast Asia, chased out by a victorious Grab. In the aftershock as their partnership collapsed, Smove was forced to restructure, renegotiate terms with its suppliers, shutter its offices in Australia and lay off employees in Singapore. But by early 2020, Lokenvitz felt they had turned the corner; they had shed most of their more expensive leasing contracts and were looking to the future, eyeing an expansion of their fleet and forays into new markets.

“In January, February, we were back on track,” Lokenvitz told the Nikkei Asian Review. “The plan was to do a funding round mid-2020 to basically say: Look, we’re overall profitable, we can look at expansion again.”

When cases of COVID-19 spiked in Singapore in May and its government slammed the brakes on free movement, it spelled a sudden end. The company’s revenue plummeted by 85%, compelling it to liquidate its operational arm and try to sell the intellectual property of its parent company.

“We were a bit of a sick patient before COVID, but we were recovering,” Lokenvitz said. “But as a company with a low cash balance, what could you do? We couldn’t get liquidity … even though there was government support. That just wasn’t enough to tide us over through the circuit breaker.”

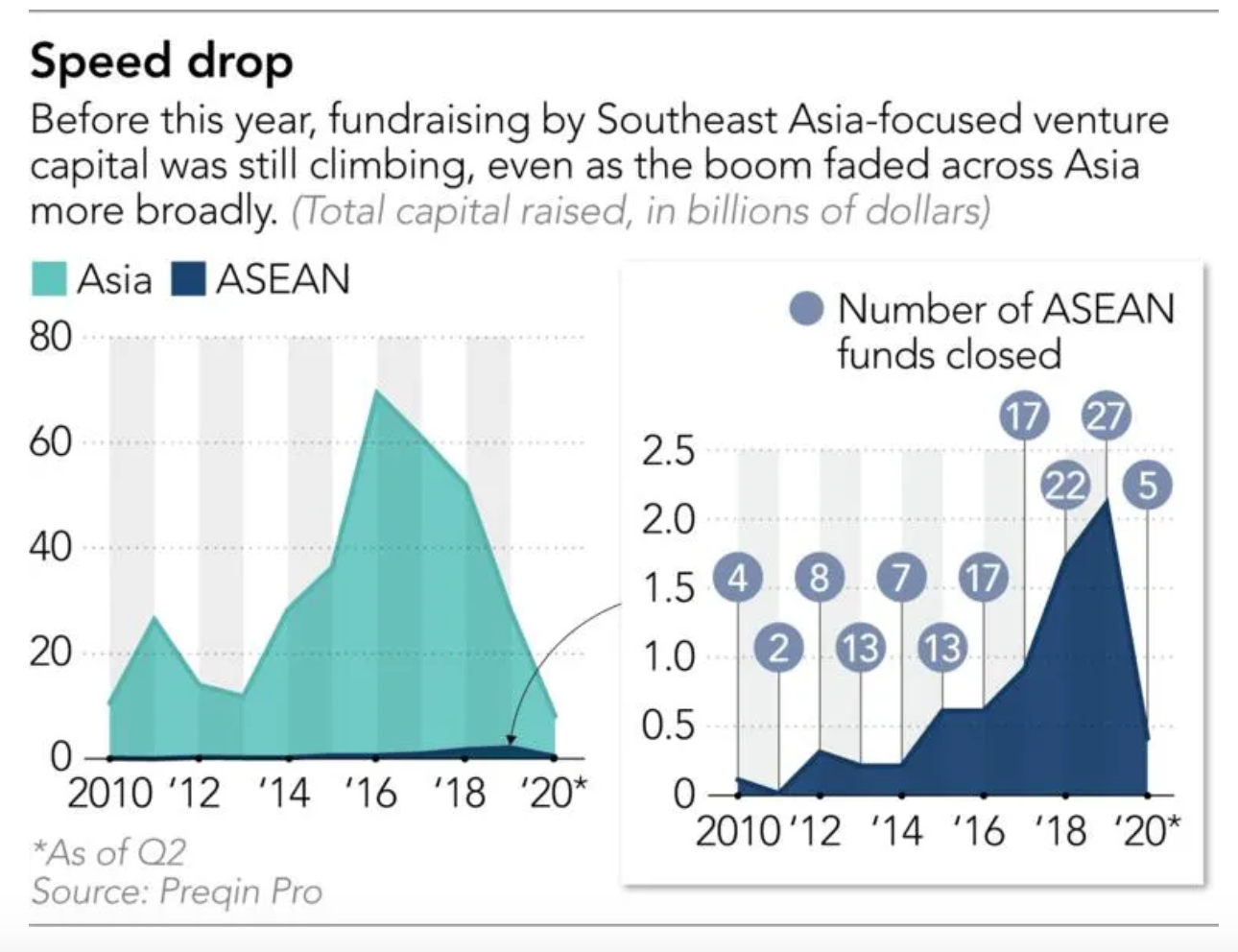

Smove is one of a mounting pile of injured, cash-bleeding young companies in Southeast Asia. The coronavirus has brought a chill to the region’s startups, for years fueled by billions of dollars in venture capital from growth-chasing investors, including SoftBank Group’s controversial USD 100 billion Vision Fund. Fissures in the capital-fueled model that underwrote the boom are becoming exposed: Valuations are shrinking, venture capital-raising has brushed a seven-year low, and the unicorns for whom profit was a theoretical goal are suddenly being forced to make deep cuts and hard decisions.

In this more sober environment, the attractions of Southeast Asia as a growth play have stuttered. In a market that was expanding by double-digit percentages each year, and where unicorns seemed destined to progress to decacorn status, the coronavirus correction is a reality check for investors and a setback for the region’s burgeoning startup ecosystem — at least until the pandemic is brought under control.

This could be a shakeout moment, said Chandra Firmanto, managing partner at Jakarta-based Indogen Capital. “Investors were not paying attention to unit economics. Many of them were just [saying], it is a hot industry, it is going to be big … because it was very easy to raise money.”

Unicorn blood

In Jakarta, the unicorn bloodletting has begun.

In 2010, a tiny company named Gojek — taking its name from ojek, a two-wheeled bike whose rider could be hailed out of the chaotic traffic from a street corner — started life as a call center with a handful of employees, connecting consumers with couriers and rides. By 2015, it had developed an Uber-style app and become Indonesia’s first unicorn; by 2019 it had passed a USD 10 billion valuation and was well on its way to becoming a “super app,” spanning everything from ride-hailing to digital payments to housecleaning. In some ways, it had surpassed the ambitions of even its predecessor Uber.

Gojek and its founders were tracking the growth of Southeast Asia’s booming startup sector, where venture capital fundraising would swell more than 20 times in the decade leading up to 2019. The company was playing a key role in bringing Indonesia’s intensely local commerce into the growing digital economy — just as investors wanted first access to an increasingly prosperous, mobile-connected market. Names like Google, Tencent Holdings, and Facebook piled onto its list of backers.

To skeptics, there was more money than ideas washing around Indonesia’s burgeoning startup ecosystem. But as the archipelago’s internet economy headed to hit an estimated USD 40 billion in 2019 — a fivefold increase from 2015, and a fact proudly touted by President Joko Widodo — Gojek’s ambitions became embedded in its super app strategy. “Anything that the middle class in Indonesia and beyond want to transact with, we want to centralize it within this one app,” said founder Nadiem Makarim back in 2018.

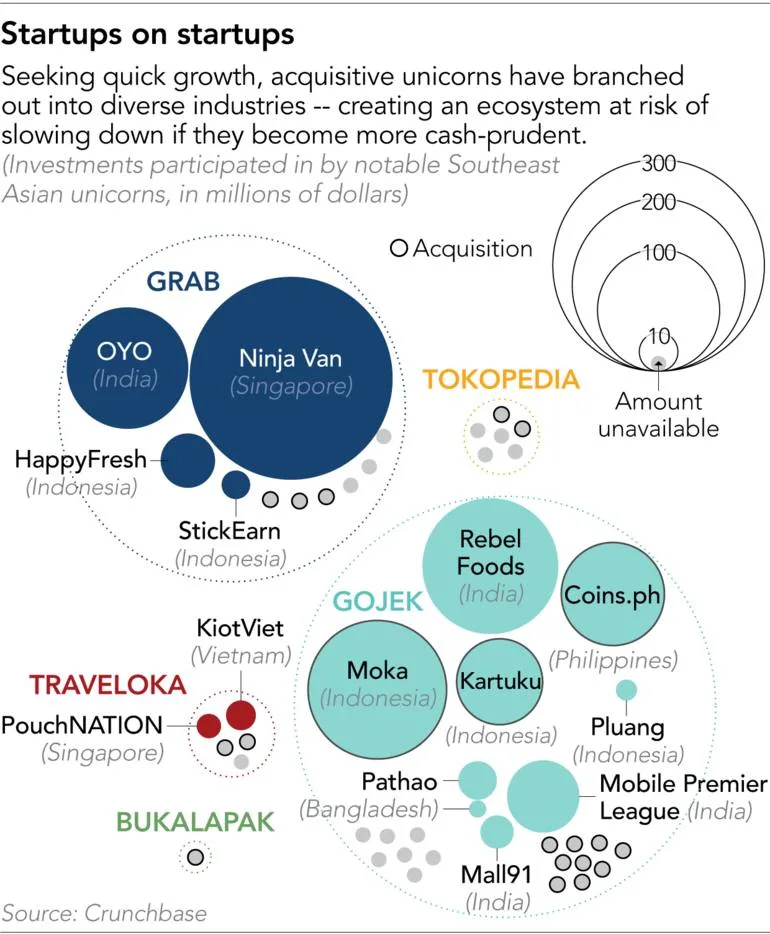

The idea was that by concentrating multiple daily services on its platform, consumers would be tied to Gojek’s ecosystem, increasing their use of other core services like ride-hailing and payments. Millions of investment dollars flowing into the company were shouldering the cost of expanding into areas from food delivery to massage, partly through acquisition of yet smaller startups.

It was not alone: Rival Grab also sank millions into at least 10 smaller startups over the three years to early 2020. Neither company was believed to be profitable in 2019, trapped in a competition of offering discounts and subsidies that aimed to lure both riders and drivers to their platforms.

If anyone had the capacity to spend their way to growth, it was Gojek. Its core services had already become necessities in the daily lives of Indonesians, and they wanted more. But by late June, as consumer activity collapsed, the company had announced it would lay off of 9% of its workforce and shut down GoLife, a service offering home cleaning and massage services, as well as GoFood Festival, the company’s physical food courts. It had already closed GoGlam, a beautician booking service, and GoFix, a home appliances repair service, in January.

It also threatened the livelihoods that many ordinary Indonesians had built with the help of these apps. “It was quite shocking,” said Asri Sulastri, a former cleaner for the maintenance business GoClean. Thousands of cleaner-partners like her have been left stranded by the closure. “I thought, ‘Gojek is a big company — surely they will keep expanding types of services.'”

As countries uneasily lurch between rolling back and reimposing distancing controls, companies that enthusiastically mapped onto Southeast Asia’s growing consumer demand are having to cut back to their core.

Traveloka, Indonesia’s answer to Expedia, was forced to lay off around 100 people — 10% of its employees — in early April, as the global travel industry was crushed by closed borders and hypervigilant governments. After restructuring, the company was able to raise an additional USD 250 million in July. Singapore’s ride-hailing unicorn Grab, in April, offered voluntary unpaid leave or reduced working hours for employees in departments with excess capacity. In June, it laid off about 360 staff, or 5% of the total.

“I know this team — this is a very painful thing for them. If it is not necessary, they will not do it. I think they have no choice,” said Chua Kee Lock, CEO of Vertex Holdings, an early investor in Grab.

Smaller startups that lack similar financial means have been forced to shut down for good. Stoqo Teknologi Indonesia, a popular online platform that supplied fresh ingredients to mom and pop food outlets, ceased operations in late April after COVID-19 “drastically decreased [its] income.” Another casualty was Airy, a budget hotel startup; it stopped operations at the end of May after seeing a “very significant decline in sales and very high refund requests from users” over the past few months.

A step down the food chain, a slew of even smaller startups are being forced into a corner. Singaporean fintech company FOMO Pay let go of part-time staff and deferred overseas expansion, seeing digital payment transactions decline more than 50% in February as the outbreak intensified across the region. Malaysia-based flower delivery startup BloomThis saw revenue drop 90%, causing its chief executive to cut all marketing expenses, ask his landlord for help, seek aid from banks, and consider reducing salaries.

In many ways, the Southeast Asia boom was already losing steam. As investors watched the initial public offerings of Uber and Slack Technologies belly-flop in the spring of 2019 in the US, and WeWork’s own attempt collapse the moment it filed its IPO prospectus in August, the myth of the ever-growing startup had begun to unravel. By one set of data from DealStreetAsia, the region had seen a dip of 30% in funding value through last year, concentrated in the second half after IPO disappointments mounted. Many larger startups — including Gojek — were already in transition before the pandemic hit, quickly pivoting their messaging toward “paths to profit” as growing scrutiny from their backers prompted a reassessment of the “growth-at-any-cost” philosophy of the past few years.

Fund managers say that, as a result, startup valuations have broadly contracted by around 20% to 30% compared to this time last year. The arrival of the coronavirus only accelerated a shift already in motion.

“This crisis has proved that this kind of growth is very fragile,” said Amit Anand, co-founder and managing partner at Singapore’s Jungle Ventures. “Valuations and value creation have to go hand in hand. There is no harm in companies and investors seeking growth or higher valuations, but they have to also unlock corresponding value.”

Counting cash

“COVID-19 came at a very bad time for us,” one founder at an Indonesian e-commerce startup said, crestfallen. The startup had carved out a niche in the market selling a specialized product, and although still running at a loss, the company had what it and investors thought was a clear path to profitability. Having already gone through early funding rounds, it was in talks to receive fresh capital to accelerate growth.

Those conversations quickly dissipated as the coronavirus made landfall in Indonesia in early March. The country was one of the last in Asia to report cases, but the count soon jumped to reach the highest tally among the ASEAN grouping.

“Overseas investors got cold feet,” said the founder, who asked not to be named. “We basically had secured funding to give us around 18 months of runway and it was pulled at the last minute. One was a term sheet [a nonbinding document that lays out terms and conditions for investment], another was a written commitment, a signed agreement. The former we can understand, but the latter was devastating because we counted on that one.”

Rather than jostling to outbid each other on valuations, investors are instructing their portfolio companies to adjust their business plans and hold tightly onto cash reserves, aiming to build a “runway” for at least another year, sometimes by making painful cost cuts. They are also scrambling to secure commitments from investors for new funds.

“Now a lot of these [investment] players have all disappeared,” Vertex’s Chua said. “We have been looking at a lot of deals, [and] there are very few people talking to entrepreneurs, negotiating term sheets. Very few.” For some startups, the investment fund is the only one they’re in talks with, according to Chua. “I’m very surprised. [Some companies] have never seen that ‘only guy’ kind of scenario.”

For those remaining, there is still some room for opportunity. In some cases, the terms of investment have shifted: Companies are increasingly raising funds in convertible bonds and loans, meaning a canny investor could, in the future, purchase a stake at a discount.

Speaking at a recent webinar, Abheek Anand, managing director at the venture capital fund Sequoia Capital, said the firm believes it is “a very interesting time,” because “the really good businesses start to stand out, and competitive intensity starts to lower.” Half a dozen funds, including Sequoia Capital, one of the most active in the region and which just closed a USD 1.35 billion Southeast Asia fund, declined to comment for this story.

Data from Preqin shows ASEAN-focused VC funds raised close to USD 400 million in the first half of this year, meaning there is still some dry powder for startups in the region — provided they can show their ability to survive or even profit from the changes in society COVID-19 has enforced.

“We are investing right now. We have a new fund coming up, so we are trying to free up the pipeline before we are ready to engage [with startups],” said Benny Tjia, principal at Indogen Capital. “We are looking at a few companies now that are in the ‘pandemic growth sector’ … companies in esports, health care, and logistics. They have been affected by the pandemic, but not as much as other sectors.”

Various startup funding rounds have closed in the past few months, albeit including some in train from earlier this year. Kopi Kenangan, a grab-and-go style coffee chain that says it is already showing profitability, raised USD 109 million in a Series B funding round in mid-May. Other startups that have been able to recently raise funds include Bobobox, a Bandung-based capsule hotel company; Delman, a big-data management and analytics provider; and Kargo Technologies, a freight logistics marketplace.

“When COVID-19 started, [Kopi Kenangan] hadn’t signed anything [with the investors],” said a person close to the company. “There was no legal obligation to see through the deal. But most of their investors are long-term investors. They have a five-year-or-longer time horizon. They have been lucky.”

Then there is the false shakeout. Coronavirus caution may serve as a reckoning for some companies but it’s also an opportunity for others who knew they needed to trim some fat.

“Some companies are going to use COVID as a way of getting leaner, even though it might not have had a direct impact.” said the founder of a Singaporean tech company who asked not to be named. “It’s a good excuse, as bad as it sounds — if we have to get leaner, we have too much overhead, we were built for growth, so now we have to look at profitability. I think that’s the case for a lot of startups.”

Read more: Gaining grounds: How Kopi Kenangan brews beans into big business

New reality

Now, with coronavirus wreaking havoc in the region, even profitability is being put on the back burner. The new mantra: surviving the winter.

The biggest players are not immune to adjusting to the new reality. “As with most other companies, startups, especially in Southeast Asia, need to immediately focus on playing short-term defense, especially if they do not have deep pockets,” said Amit Joshi, a professor of AI, analytics and marketing strategy at IMD Business School in Lausanne, Switzerland. “The goal will be in riding out this storm, ideally through cost-cutting. However, for better-funded startups, this is a terrific opportunity to acquire smaller companies and further consolidate their position.”

“VCs will also look at this phase as an opportunity to get in on the ground floor in promising startups,” he added. “However, the ‘stupid money’ will dry up — so no more funding just for calling yourself an ‘AI startup’ or something. In terms of metrics, the standard metrics — burn rate, cost of acquisition, retention — will still suffice but will probably be looked at much more closely than before.”

After beginning the liquidation of Smove, Lokenvitz put a post on the social networking site LinkedIn inviting other founders to reach out, to share their concerns and to learn from his example. The response was overwhelming, and he told Nikkei that he has since spent hours on Zoom calls and Google Hangouts.

“Entrepreneurship is never easy,” he said. “It is good that people are reaching out and asking for help.”

He hopes that both startups and VCs will continue their reassessment of what success looks like. Growth for the sake of growth has become unhealthy — for companies, founders and customers, he said, adding that startups have become too focused on raising capital from investors, rather than earning money by attracting and retaining customers.

“For startups, because of the excess VC money, that moment in time where your customers become your main source of funding has been delayed over the past decade and a half,” he said.

Such patterns have taken years to set in. But in this environment, reversals can come quickly.

“When I was hired in mid-2019, the person I was hired to assist was overwhelmed due to high targets and demands from many other divisions,” said a former Traveloka employee who was a victim of the company’s layoffs. “It was around February when there was talk of coronavirus having a massive impact on the company. From then on, it just got worse.

“I heard a lot about working in startups being very vulnerable … but I thought working in a unicorn would be different. Apparently, during this [coronavirus outbreak], nobody’s immune.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asian Review. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei. 36Kr is KrASIA’s parent company.