A dozen cranes stack giant concrete structures and heavy machines roar as they dig the ground at a massive construction site in the northern part of Singapore, near the Johor Strait, where the island nation shares its border with Malaysia.

The USD 4 billion project began six months ago at the Woodlands Wafer Fab Park, one of Singapore’s semiconductor manufacturing clusters. The site will house a new semiconductor factory of US contract chipmaker GlobalFoundries, and is expected to start production in 2023.

GlobalFoundries, whose largest shareholder is Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment, already operates several chip fabs in the island nation. It is adding 23,000 sq. meters of cleanroom space and new administrative offices at the site. When completed, the company will boost annual capacity by 450,000 wafers, bringing the Singapore campus up to approximately 1.5 million wafers per year. The company also plans to expand capacity at its sites in the US and Germany.

“It took 50 years for the industry to grow to half a trillion dollars today, and now it is estimated that the industry will grow to a trillion in roughly eight years,” GlobalFoundries CEO Tom Caulfield said at the Singapore groundbreaking ceremony, which was held virtually in June, referring to the chip industry’s annual revenue. “It is hard to overstate the amount of investment and focus the industry will have to deliver to meet this challenge.”

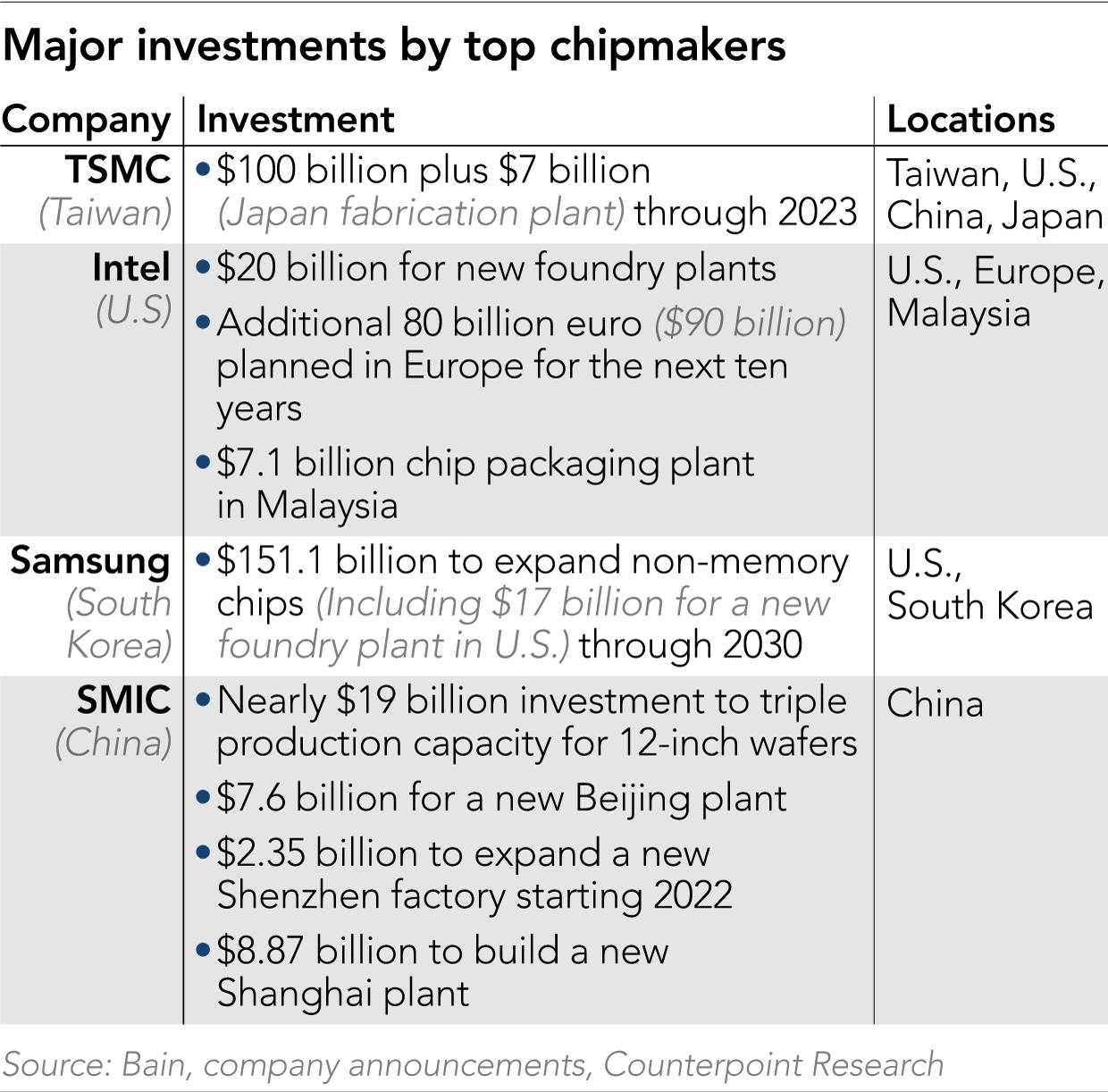

Caulfield is just one of many chip executives optimistic about the industry’s growth and it is not only in Singapore where new fabs are being planned. It is happening all over the world, including Taiwan, the US, South Korea, Europe, and Japan. Chip manufacturers worldwide—including the three giants, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Samsung Electronics, and Intel—are rapidly increasing their global manufacturing footprints and capacity.

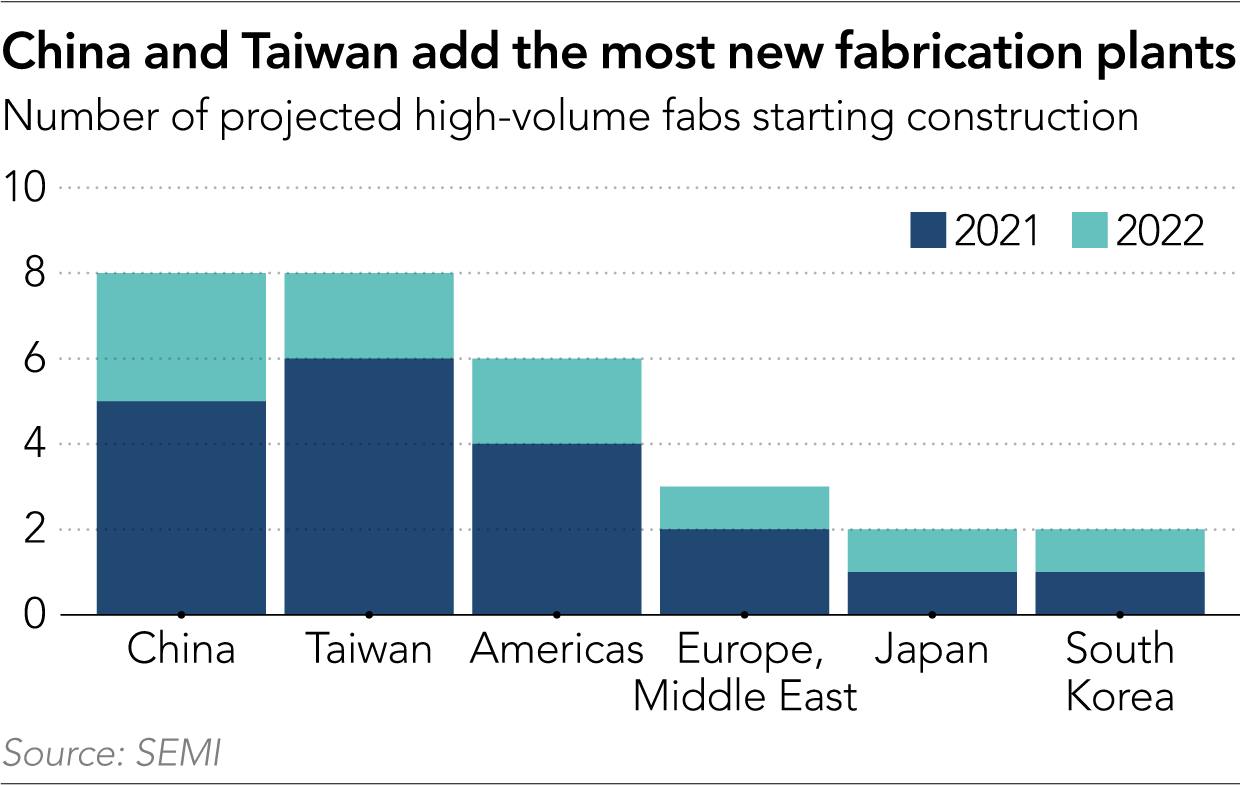

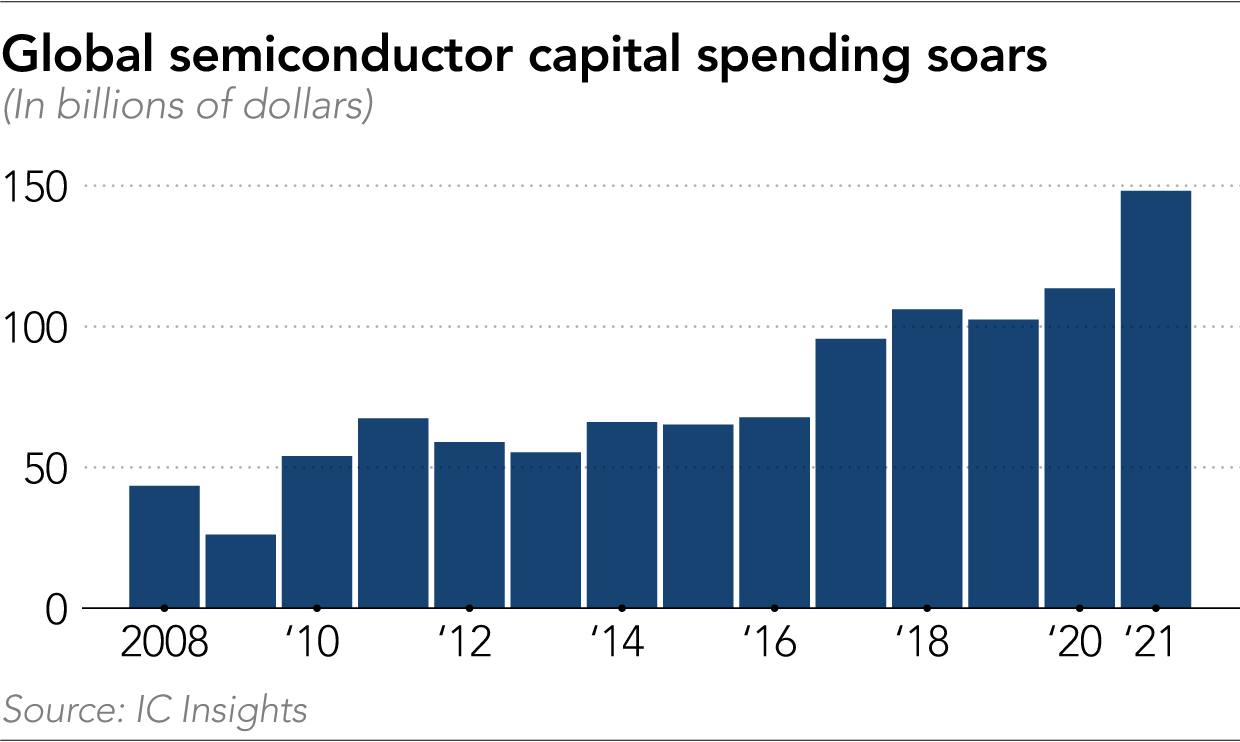

Industry organization SEMI estimated in June that construction on close to 30 new fabs will start by the end of 2022. In September it predicted global semiconductor equipment investment for front-end fabs, where the silicon wafers are processed, will be nearly USD 100 billion next year, after topping USD 90 billion this year—both records. This will mark a “rare three consecutive years of growth that began in 2020, bucking the historical cyclical trend of a one- or two-year expansion followed by a year or two of tepid growth or declines,” SEMI said.

An unprecedented global chip shortage has given semiconductor industry executives confidence to expand capacity. On top of this, governments in the US, Europe, Japan, and elsewhere have committed to spend billions of dollars to expand semiconductor production within their own borders—measures designed to protect against supply chain disruptions like those caused by the pandemic, and to reduce reliance on production in Taiwan.

Meanwhile, China, the biggest consumer of chips globally, is ramping up its own investment to achieve a goal of 70% self-sufficiency in semiconductors by 2025. Analysts at Moody’s in August said this would support China’s tech progress but that there was the potential for overcapacity and investment inefficiency, adding extra uncertainty over global chip supply and demand.

“I’ve never seen this level of government money poured into the semiconductor sector,” said Akira Minamikawa, senior consulting director of UK-based research company Omdia, who has been a close industry watcher since the 1980s.

In the past, the Japanese, South Korean, and Taiwanese governments invested heavily in the industry, “but this happened continuously over a long period of time. This time, it’s happening simultaneously,” Minamikawa told Nikkei Asia. Building resilience and minimizing dependency on the global chip supply chain means that there will be redundancy. At some point, he predicts, “there will be an imbalance between the supply and demand for sure, and it’s a matter of when that is the question.”

Minamikawa is not alone in his forecast. Research group IDC in September said the semiconductor market is on course to grow by 17.3% in 2021 versus 10.8% in 2020, with growth driven by mobile phones, notebooks, servers, and more sophisticated cars. But it said there is a potential for overcapacity in 2023 as large-scale capacity expansion begins to come online toward the end of next year.

Mario Morales, group vice president of IDC, told Nikkei that “we can argue that a lot of the capacities are going to be needed because we’re still seeing very good secular semiconductor market growth.” However, he added, “we started seeing a slowdown in consumer sentiment.” IDC expects that the growth of the PC market will likely be flat in 2022, especially after heated demand during the pandemic, as society shifted rapidly to remote work and online classes.

Morales already thinks that some of the investment plans made by chip companies might be pushed back or even canceled in the future. “I don’t think all of it will be realized,” he said. “But it’s going to be enough that I think that could turn the corner and really change the dynamics that we’re seeing.”

In fact, the fine print in the share prospectus of GlobalFoundries, which went public on Nasdaq in October, sets out risks in the industry that Caulfield and other chip executives rarely touch upon publicly.

“The seasonality and cyclical nature of the semiconductor industry and periodic overcapacity make us vulnerable to significant and sometimes prolonged economic downturns,” it states. “Overcapacity in the semiconductor industry may reduce our revenues, earnings, and margins. … Strong government support in China for capacity expansion, combined with weaker demand from and strained economic relations with that country, could lead to underutilization or significant ASP (average selling prices) erosion for fab fill.”

The giant chipmakers are planning their mega-investments at a time when the supply-demand picture is more obscure than ever. Since the chip shortage intensified from the beginning of the year, a broad range of customers—including the manufacturers of smartphones, consumer electronics, and cars—have been ordering more than they need because they fear not getting what they want.

Nobody in the industry seems to know what the actual demand is, “and that is the risk,” said Minamikawa.

“Figuring out how many orders are ‘double orders’ and even ‘phantom orders’ is a million-dollar question,” said Renesas Electronics CEO Hidetoshi Shibata, at the Japanese chipmaker’s most recent earnings announcement in October. While the company posted record profit driven by demand for chips from the car industry, Shibata said that Renesas had to exclude even some “noncancelable” and “nonreturnable” orders from earnings forecasts “since we judge some of them as inflated orders.”

“No one has any visibility in the next two years,” said Dan Hutcheson, chief executive officer of VLSI Research, who has been in the industry for more than 40 years. “We will see oversupply, but that’s not a concern. … We overproduce, and then a year or two later, we get into negative growth, we come back. That’s just the history of the industry. It’s cyclical.”

If there is a supply glut, it may not apply equally across the different types of chips.

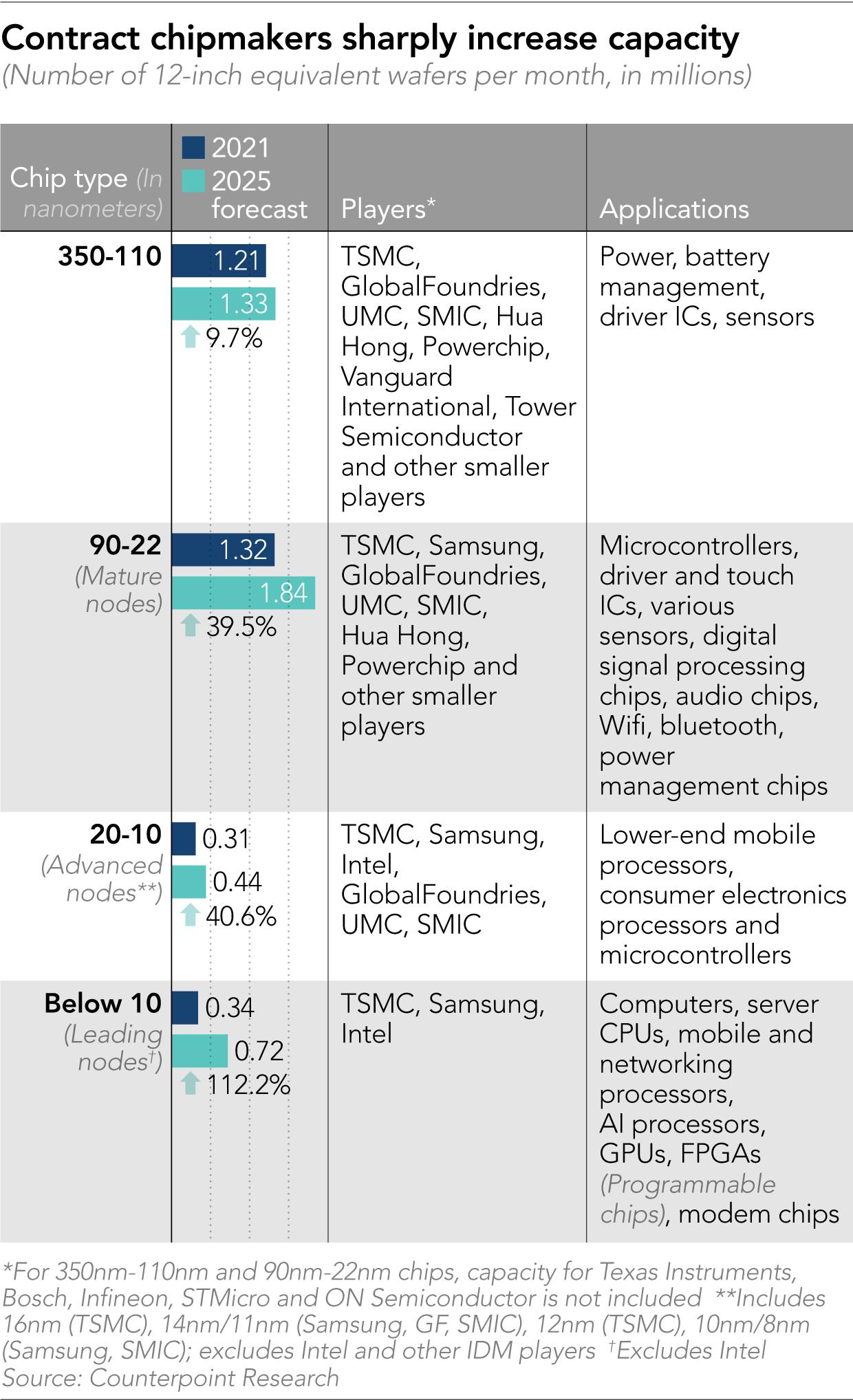

Most of the new capacity being added by contract chipmakers—like the plant that TSMC announced it will build in Kumamoto, Japan, in a joint investment with Sony Group and which will be subsidized by the Japanese government to the tune of billions of dollars—is in relatively mature technology, chips in the 22- to 90-nanometer range. The size refers to the line width between transistors on a chip. The smaller the size, generally, the more challenging and expensive the chip is to produce.

This mature technology is used in a wide range of chips from sensors and microcontrollers to power management chips, and is where the present global chip shortage has been most acute. Major contract chipmakers will increase capacity for such chips by about 40% from 2021 to 2025, Dale Gai, research director with Counterpoint, told Nikkei.

On the other hand, cutting-edge chips requiring 10-nanometer technology or finer, suitable for building CPUs, GPUs, AI accelerators, and networking processors, will more than double from now to 2025, the research agency estimates. But this expansion is from a low base. Cutting-edge production capacity only accounts for about 11% of global semiconductor output from contract chipmakers.

“We are more concerned about those more mature chip production technologies and whether that addition will be sustainable when that new capacity becomes ready by 2023 or 2024,” said Gai. “The area is much more crowded.”

There are signs of a slowdown in demand emerging already in memory chips, reflecting slower sales primarily of PCs, which were in heavy demand during the pandemic.

The bulk price of 8 GB “double data rate 4” memory—a benchmark for dynamic random-access memory used in computers—has declined for four consecutive months since August. Key players such as US-based Micron Technology and South Korea’s SK Hynix have reported a steady decline in inventory. Micron in September announced a financial forecast for the fiscal first quarter that was well below analysts’ expectations.

Companies are urging their investors to think long term and to consider structural changes that will justify increased capacity.

“The way we look at the factory is always long term,” Helmut Gassel, chief marketing officer and member of the management board of Infineon Technologies, a German chip giant, told Nikkei. The company recently opened a new fab in Villach, Austria, to ramp up output of power semiconductors primarily used in the auto industry, particularly in electric vehicles and hybrids.

“When we announced the manufacturing … site in Villach in 2018, people were wondering. And now they all are thinking we did great,” Gassel said. “We have grown as a company—10% per year for over the past 20 years—and you know you have to build the next step in order to be able to serve the market,” he said. “When you believe in structural growth and continuous growth, then you will need to add fabs. And when you add too many at one point? Well, then you will have a break. But eventually, demand will always grow to the capacity that has been built.”

Gassel may be right. Although the demand for smartphones and PCs may decline over the year, new applications such as EVs, autonomous vehicles, the Internet of Things, and smart cities will surely emerge. Shifts to cloud computing driven by heavy investments in data centers filled with servers, made by cash-rich US companies, will also increase.

But it is also true that the chip industry has experienced significant fluctuations, saddling manufacturers with excess capacity built up during boom years once the market cools. “The only way to minimize this risk is to make precise demand forecasts, but this is very difficult to do, especially in the current market condition,” said Minamikawa.

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.