The specter of COVID-19 looms over China’s ongoing Lunar New Year holidays. The government discouraged the usual stampede of travelers heading home for family reunions. Businesses fear for their bottom lines. But 50,000 Beijingers received a small pick-me-up: RMB 200 (USD 31) in digital “red envelopes” they can use for shopping online or offline.

The authorities see this as a stepping stone to something much bigger.

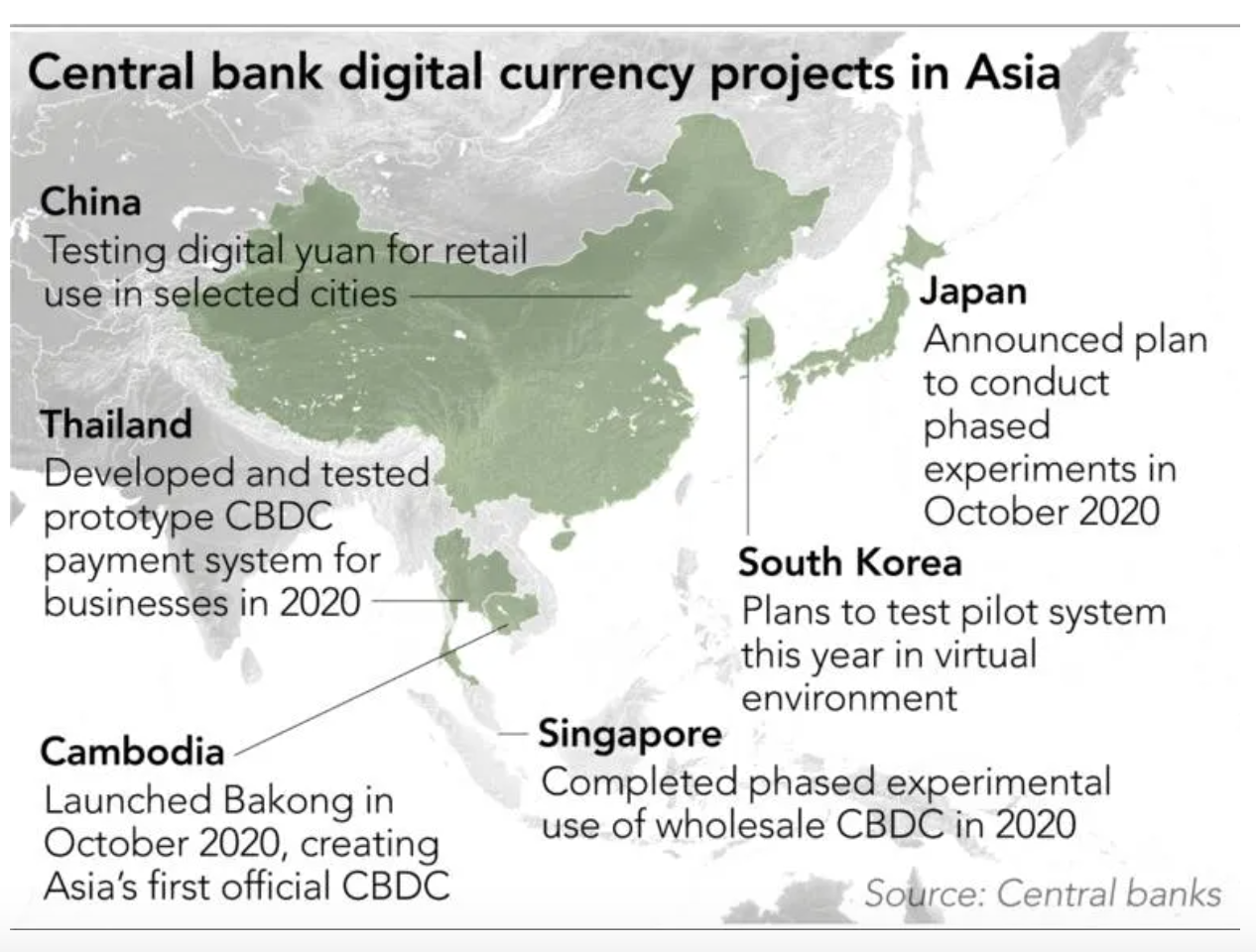

As the pandemic accelerates digitalization, central banks worldwide are increasingly looking into issuing electronic forms of fiat currencies. Last October, Cambodia became the first Asian country to formally launch such a system. Numerous others, from Thailand and Singapore to Japan and South Korea, are conducting research and trials.

China’s push for a “digital yuan,” however, may have the greatest potential to impact the global economy, considering the government’s ambition to internationalize its currency.

Beijing’s weeklong trial ends on Wednesday. A similar test has been held in Suzhou, and including earlier trials, the People’s Bank of China has distributed over 100 million digital yuan so far. More e-yuan programs are planned during the Beijing Winter Olympics in 2022.

China is no stranger to digital money. Hundreds of millions of consumers use the Alipay and WeChat Pay services, scanning QR codes on their smartphone screens instead of fumbling for notes and coins. The digital yuan works much the same way.

But it is not the same, as the Bank for International Settlements explains.

A central bank digital currency (CBDC) is a “central bank-issued digital money denominated in the national unit of account, and it represents a liability of the central bank,” the BIS says. Unlike existing e-money and cryptocurrencies, the bank continues, a CBDC represents a direct claim on a central bank rather than a liability on a private financial institution.

A BIS survey released in January revealed that 86% of 65 central banks that responded were actively engaged in some form of CBDC work. Nearly 60% said it was either “likely” or “possible” that they would issue a CBDC for retail use in the next six years.

If Facebook lit a spark under central banks by threatening traditional finance and monetary sovereignty with its Libra digital currency project, now called Diem, COVID-19 has added kindling. In the BIS survey, nearly 30% said the pandemic had “changed their priority or preference” for issuing CBDCs.

Top reasons included improving access to money in emergencies, complementing cash when social distancing is required and establishing a conduit for public funding programs.

Emerging economies with relatively weak existing systems have their own motivations to pursue CBDCs as tools to expand financial inclusion, enable efficient payments and enhance monetary policy.

Cambodia is a prime example.

The National Bank of Cambodia last October launched a payment system called Bakong, codeveloped with Japanese blockchain startup Soramitsu.

Kazumasa Miyazawa, Soramitsu’s president, told Nikkei Asia that the NBC wants to increase the presence of its own currency, the riel. Most transactions in Cambodia are conducted in dollars. At least, Miyazawa suggested, the NBC wants to “avoid their own currency’s presence shrinking” further.

This comes as the prospect of digital yuan proliferation grows. Many wonder how Beijing would fit its e-currency into global strategies, including efforts to influence emerging countries through the Belt and Road Initiative.

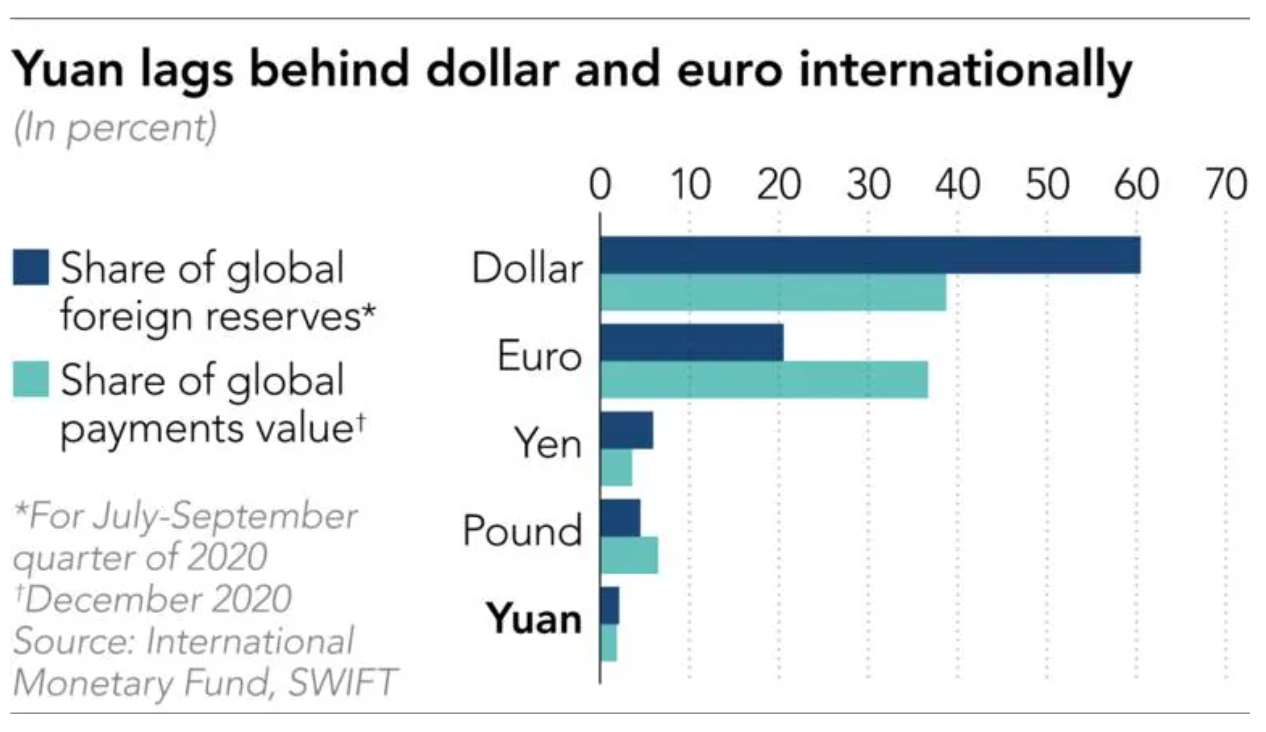

Despite China’s status as the world’s second-largest economy, the yuan or renminbi lags far behind other international currencies. It accounted for 2.13% of global foreign reserves in the third quarter of 2020, according to the International Monetary Fund. Its share of global payments was just 1.88% in December, according to SWIFT, a provider of secure financial messaging services.

But Miyazawa said that “the digital yuan could go into developing nations in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.” He also noted that China is encouraging local and foreign banks to use its Cross-border Interbank Payment System, a competitor to SWIFT, which could increase the ratio of yuan in international transactions.

Analysts at Singapore’s DBS Bank highlighted the digital yuan’s potential in Africa in a recent report, pointing out that Huawei Technologies’ new smartphones have a built-in digital yuan wallet.

“With the preinstalled digital wallet, e-RMB going forward could be exported overseas more efficiently,” the analysts wrote, using the abbreviation for renminbi. “Africa, for instance, is well-positioned for the rapid adoption of the digital yuan” thanks to China’s strength in the continent’s consumer device markets.

“The yuan, given its stability, could be integrated into [Africa’s] payment ecosystem that is increasingly dominated by Chinese companies,” the DBS analysts wrote.

Zhu Min, the chairman of China’s National Institute of Financial Research, downplayed the notion of a global digital yuan or an integration into Belt and Road projects during the Davos Agenda meetings in late January. Still, he stressed that digital currencies “can and will move” across the world depending on market needs and governments’ bilateral agreements.

“The digital currency will move into different areas,” Zhu said.

Even if the immediate global implications are limited, the domestic impact could be considerable. The digital yuan poses a potential threat to China’s prevailing forms of e-money, Alibaba Group Holding’s affiliate Ant Group’s Alipay and Tencent Holdings’ WeChat Pay — especially now that Beijing is tightening regulations on fast-growing fintech players.

“It is very likely that in the future, all digital payments will need to be settled in the new digital yuan, which would impact the role that Alipay and WeChat Pay play in the settlement of transactions,” Zennon Kapron, director of financial research firm Kapronasia in Singapore, told Nikkei.

“The percentage fee that they typically charge for any merchant transaction will likely be significantly less with this new settlement structure,” he said. “This is a big issue, especially for Ant Group, which is having to restructure, putting its payments business in a separate business entity.”

Then there is the question of how much power CBDCs could give governments — not just China’s.

Digital currencies are considered an effective means to prevent money laundering and other criminal activity, but this also means authorities have more control.

“Clearly one of the benefits of CBDCs for governments is the increased visibility that [they] provide in seeing how individuals and businesses handle money,” Kapron said. “Adding to the complexity is that many CBDCs will be ‘programmable’ insofar that the issuer could control how the money is moved or used.”

This could have pros and cons, he explained.

“As an example, a certain amount of a CBDC may be earmarked for use for [small and midsize enterprise] lending, preventing banks from lending to entities other than SMEs. This can be useful in certain markets where SMEs are underserved by banks by choice, and can be positive for the growth of the overall economy,” he said.

The flip side? “This control could be negative in circumstances where the government doesn’t have the best interests of the individuals in mind or when they are facing a crisis,” Kapron said.

Regardless, CBDC projects continue in other Asian countries, too.

The Bank of Thailand last year tried a prototype CBDC-based payment system for businesses. This was integrated and tested with the procurement and financial management systems of Siam Cement Group and its suppliers. The bank said the goal was to enable “higher payment efficiency for businesses, such as increasing flexibility for fund transfers, or delivering faster and more agile payments between suppliers.” A report on the outcome is due this month.

The Bank of Korea will test a pilot CBDC system this year in a virtual environment. “We are studying CBDC seriously in case we need to issue them,” Gov. Lee Ju-yeol told reporters last month. He denied being behind other countries in the field and said, “In fact, we are speeding up.”

Just across the water, the Bank of Japan last October released its own plans for CBDC trials, with the first experiment expected in the fiscal year starting in April.

Yet none of these central banks have confirmed when they will issue their own digital currencies. If they do, they can look to China and certainly Cambodia for a lesson in the challenge of raising awareness.

During an earlier trial in China’s Suzhou in December, an apparel store in a large mall told Nikkei that only one or two customers paid with digital yuan a day. Consumers may not be in a rush to ditch Alipay and WeChat Pay, which offer extra conveniences like deliveries and ride-hailing.

At Phnom Penh’s Orussey Market — a cramped but colorful shopping hub filled with everything from food to fabric — many merchants had not even heard of the central bank’s Bakong system.

One merchant who attended a launch event in 2019 said the technology worked well but was rarely used. “Maybe 10 to 15 people have used Bakong to pay,” she said. “It is not so well-known, not yet a big hit.”

The NBC says that from the July 2019 “soft launch” to the end of 2020, average monthly transactions in riel doubled to around 16,000. Transactions in dollars quadrupled to about 80,000. The respective total values for the period stood at KHR 55 billion (USD 13.5 million) and USD 48 million.

“Since Bakong is built on new and modern technology, customer awareness programs are needed to increase further understanding of the benefits everyone can derive from using this system,” Chea Serey, the central bank’s director general, told Nikkei. She said other challenges include network connections and individual banks’ efforts to ensure customers have easy access.

“We probably need more time to observe how [Bakong] is evolving and what else we can do to promote the acceptance and usage.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.