This article first appeared on Nikkei Asian Review. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei. 36Kr is KrASIA’s parent company.

SHANGHAI/GUANGZHOU — When 38-year-old Li Bencai, owner of a wool-processing factory in China’s Hebei Province, traveled to the pastures of Xinjiang Autonomous Region this summer to buy wool, he borrowed money from online lender MyBank, an offshoot of Alibaba Group Holding.

Li borrowed 250,000 yuan (USD 35,000) of the 1 million yuan he needed to buy 50 tons of wool at an annual interest rate of 12%. Though not cheap, Li says he can still make a profit after he receives payments from apparel and textile companies after shipping the wool this month.

The mobile banking units of e-commerce giant Alibaba and internet conglomerate Tencent Holdings are changing the landscape of financial services in China, lending to more than 100 million people so far, including those in rural areas and microbusiness owners.

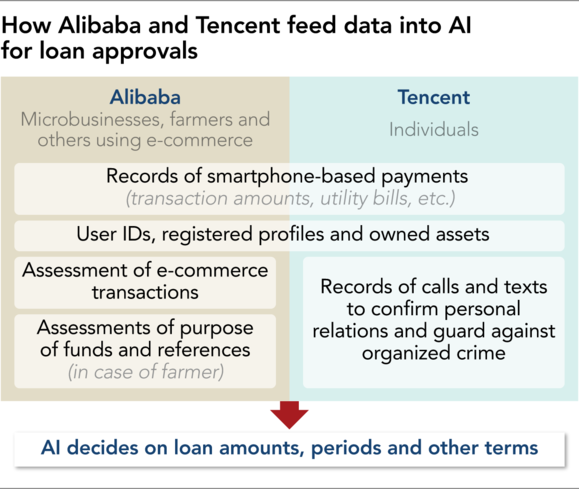

Farmers and microbusinesses — which employ no more than nine people — that previously had trouble securing loans from conventional banks are reaching out to Alibaba and Tencent for help. Both companies make their lending decisions by artificial intelligence, processing vast amounts of information gathered from the mobile payments they handle.

The two companies control more than 90% of smartphone-based payments in China. The total transactions they handled in 2018 came to around USD 25 trillion.

And how long does it take to make those lending decisions? One second.

MyBank calls its lending procedure “3-1-0.” It refers to the three minutes it takes for a loan applicant to input necessary information, one second for AI to decide whether to extend a loan and zero staff required.

For factory owners like Li, who operates a dozen spinning machines in his cottage industry, the online bank has revolutionized his way of doing business and given him more opportunities.

When Li sells his fabrics to textile companies, he adds a 15% to 20% processing fee to the material cost. He can make money even with the 12% interest rate of MyBank.

Yang Wansui, a nearby farmer, also borrowed 30,000 yuan, or USD 4,200, from MyBank to buy maize seeds and was able to plant more this year thanks to the fresh funds.

“The application of AI has made it possible for ordinary people and microbusinesses to gain access to banks,” said Wu Haishan, vice general manager of WeBank, a smartphone bank backed by Tencent in late June.

For these borrowers, easy access to loans trumps privacy and data protection.

MyBank began operating in 2015 and has extended loans to 17 million microbusinesses and other companies in the first four years. Of those, 80% had never borrowed from banks before. Total lending by MyBank has amounted to 3 trillion yuan.

“In three years’ time, street vendors will be able to borrow from us in one second,” Hu Xiaoming, chairman of the bank said in June.

Mobile banking has been a huge success in China because of the huge increase in the use of mobile payments. Alibaba and Tencent each have 1 billion users of such payment services. Almost all but the elderly and children have installed both companies’ apps in their smartphones.

They switch from Alibaba to Tencent and back for payments at convenience stores and restaurants as well as for personal remittance and online shopping.

In places other than remote locations, most stalls have QR code scanners to accept payments by customers. Even temples now take offerings via mobile payments. Cash is now increasingly rejected due to a lack of change at shops.

Given the vast trove of customer information that both companies have, they are able to make judgment calls on individuals’ income and payment ability. For example, those who pay their utility bills regularly are assessed as being able to meet repayment schedules.

Alibaba offers different interest rates to different clients based on their default risk. It is able to calculate the maximum loan amount, interest rate and default risk of each client from the data it has collected about them.

Tencent, which does not have its own electronic commerce business but operates social networking sites that reach more than 1 billion users, has developed a system for screening loan applications based on its operational features.

It has compiled a list of people eligible to receive loans on the basis of not only their payment records but also calls and social networking messages via their smartphone. It then solicits loan applications from users by advertising directly to them on their screens.

Since the user has essentially already been screened in advance, Tencent users can receive the money three minutes after applying.

Tencent has already offered credit lines to more than 100 million people, 80% of whom have no higher academic qualification than high school. Many of them are ineligible for loans from conventional banks.

So far, the ratio of nonperforming loans is as low as around 1% at MyBank and WeBank. In part, this is because Alibaba and Tencent stop borrowers from using mobile payment services when their loan repayments fall into arrears, a penalty that causes a great deal of inconvenience in China.

Critics said the danger is that Beijing can readily lean on Tencent and Alibaba to obtain detailed information on individuals. While financial inclusion is advancing at an explosive pace in China, the trade-off for individuals is the surrender of privacy.

Another concern is an increase in household debt. According to the Bank for International Settlements, the ratio of household debt to gross domestic product in China exceeded 50% at the end of 2018, nearly triple the figure 10 years ago. Households have emerged as the third pocket of excessive debt after local governments and companies.

People’s Bank of China data shows the ratio of household debt to disposable income rose to 112% in 2017 from 43% in 2008. The numbers do not include the more than 1 trillion yuan in personal loans made through online finance, which would add to the debt pile.

In 2018, the authorities tightened controls on online financial intermediaries, forcing more than 1,000 companies to suspend operations. If mobile banks become more popular and household debt mounts, China’s financial risk could also increase.