Ajinomoto, the 112-year-old Japanese food maker most famous for its monosodium glutamate seasoning, has emerged as a surprising beneficiary of the upheaval caused by the pandemic.

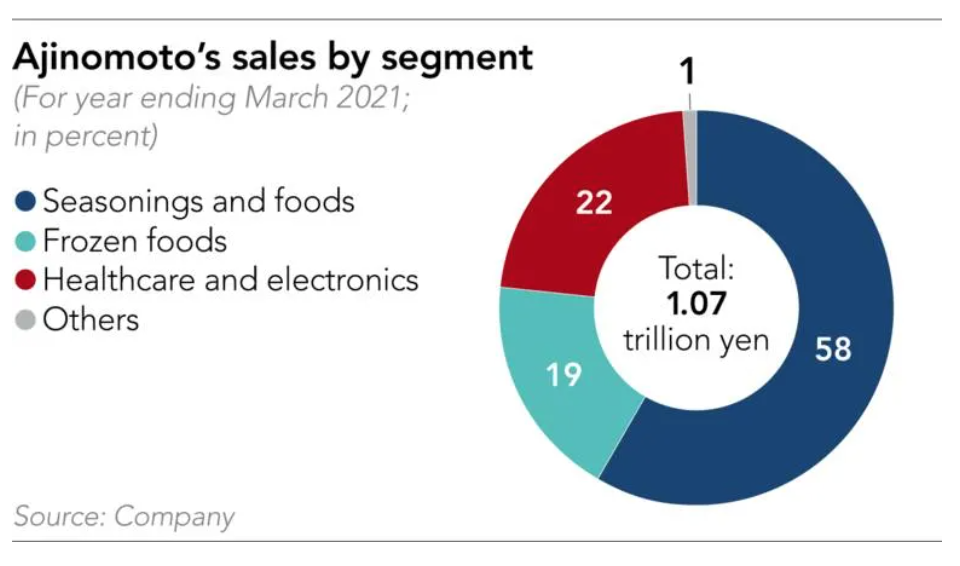

While its spices and sauces have struggled as lockdowns devastate the restaurant industry, the company’s unexpected sideline as a supplier of a high-tech film for the computer chip industry has been booming—helping Ajinomoto report a record operating profit last quarter.

Ajinomoto illustrates Japan’s ability for corporate reinvention, much like Fujifilm transformed itself from a maker of photographic film into a pharmaceuticals powerhouse and Olympus turned itself from a struggling camera maker into the leading manufacturer of endoscopes.

But analysts now want to know how far and how fast Ajinomoto can move beyond its roots in the food industry.

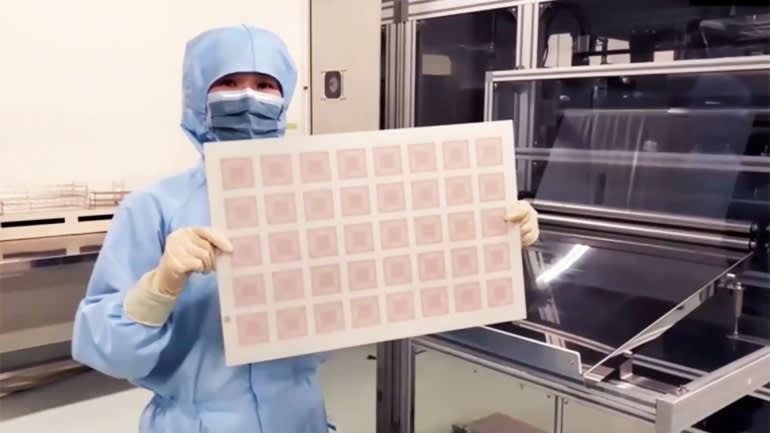

“ABF is inside most of the desktop and laptop PCs people use,” said Shigeo Nakamura, the company’s head of chemical products, referring to “Ajinomoto buildup film.” ABF is a thin composite used to attach a processor to a base layer called a substrate, forming part of a chip package that connects the chip to the motherboard and protects it from damage.

ABF substrates are used widely in the high-powered computing chips found in satellites, 5G base stations, and self-driving cars. The coronavirus unleashed huge demand to upgrade IT infrastructure—and triggered an agonizing global chip shortage. Ajinomoto’s sales could be even higher if its customers were able to scale up more quickly to meet demand.

The stock market has rewarded Ajinomoto with its highest share price in five years, and the business segment that includes electronics and health care accounted for 23% of the company’s overall operating profit in the year ending March 2021.

“Every company needs to review its business portfolio regularly,” said Makoto Morita, equity analyst at Daiwa Securities. “That’s especially the case for Japanese food makers, which face a shrinking population in their home market.”

Morita wants Ajinomoto to be even more aggressive in reshuffling its portfolio. Global food makers like Nestle, Danone, and Unilever, he said, make more acquisitions and divestitures than their Japanese peers. “Ajinomoto could do more.”

‘Now we have a much broader customer base’

People still seem surprised when they learn about Ajinomoto’s semiconductor business.

“I’m often asked by customers in Japan and overseas why Ajinomoto is involved in electronics,” said Nakamura, a bioengineering graduate from the Tokyo Institute of Technology and a University of California Santa Barbara alumnus who was one of the original developers of ABF in the 1990s.

For over a century, Ajinomoto has made food including seasonings, soup bases, dry soups, and frozen foods. Though today it uses natural ingredients such as sugar cane and cassava to make seasonings, for some of its history the company made products through chemical synthesis, allowing for more precise mass production, and many employees were engaged in chemistry research.

When Ajinomoto stopped chemical-based production in 1973, the researchers decided to do something new, Nakamura told Nikkei Asia, explaining how the chemicals division got its start.

It was not obvious that a food company would be able to make a semiconductor material and convince chipmakers to use it. Such material needs to meet many requirements, such as good adhesion and heat resistance as well as being nonconductive. It also has to be inexpensive and easy to handle. Chemical products that meet these requirements had been found during research on protein and amino acids—key seasoning ingredients. Still, few expected Ajinomoto to come up with semiconductor material.

When ABF hit the market in 1999 and won its first customers, the growth was rapid. Ajinomoto does not disclose its end users, but ABF substrates are believed to be embedded in computer processors made by Intel and Advanced Micro Devices.

Sales plateaued between 2008 and 2016 in part because ABF wasn’t used in chips for smartphones, the dominant device of the era, but the pandemic sparked a surge in demand for PCs as remote learning and teleworking took off worldwide. Demand for ABF was further fueled by the rush to build data centers for cloud computing and base stations for 5G networks.

“We only had PC makers as customers before. Now we have a much broader customer base,” Nakamura said. The company’s factory in Gunma, north of Tokyo, has ample room to boost production, he said. It currently operates on a single shift, and output can be doubled by simply introducing a second.

Unimicron, a Taiwanese printed circuit board maker that is one of Ajinomoto’s big customers, says it is spending up to USD 2.56 billion to expand production capacity for ABF substrates over the three years through 2023. The planned supply is already fully booked through 2025.

“We keep increasing our annual capex, as the current situation is whatever capacity for ABF substrates we have, the clients want them all,” Unimicron president Michael Shen told investors last month.

Thanks to customers like Unimicron, Ajinomoto expects ABF shipments to more than double in the five years to 2024.

‘The earnings driver of the company’

Ajinomoto shares are up 80% in two and a half years, and analysts who were once sour about the slow-growing company now heap praise on it.

“Well ahead of expectations,” SMBC Nikko Securities analyst Naomi Takagi said about the April-June earnings, giving the company’s shares an “outperform” rating.

Investors have focused on prospects for its non-food segment, disparate businesses mostly in the area of health care that include liquids used in intravenous drips, materials for cell cultivation and contract drug manufacturing, as well as ABF.

“We expect the non-food segment to account for 60% of the profit increase in the next three years,” said Hiroshi Saji, equity analyst at Mizuho Securities. “This segment will be the earnings driver of the company.”

This enthusiasm represents a turnaround for Takaaki Nishii, CEO since 2015. In his first four years, Nishii presided over a tumbling share price and investor dissatisfaction, as an overseas expansion plan begun by predecessor Masatoshi Ito gradually fell apart.

Ajinomoto had long harbored an ambition to rival global food giants such as Nestle. Under Ito, it embarked on an epic deal-making spree in a bid to boost overseas sales.

The company made a series of acquisitions in Turkey between 2013 and 2017. In the US, Ajinomoto bought frozen food maker Windsor Quality Holdings for about USD 800 million in 2014. In South Africa, it acquired food maker Promasidor for USD 532 million in 2016. In Japan, it turned a beverage-making foreign joint venture Ajinomoto General Foods into a wholly-owned unit for about USD 245 million in 2015.

But many of the foreign acquisitions failed to pay off, forcing the company to write down much of these assets by 2019. Investor confidence plummeted.

In November 2018, Nishii abruptly announced a shift to “asset-light management,” signaling that the company would restructure unprofitable operations and focus on promising areas such as ABF.

Investors were skeptical. “Is the current management capable of executing the new strategy? How could management that has been behind the curve carry out a reorganization of the company?” according to one question asked in a January 2019 earnings call.

Some sort of action was needed, given the powerful competitors facing Ajinomoto both in Japan and abroad.

In the beverage market, its powdered coffee faces a challenge from Nestle. In frozen foods, Ajinomoto trails domestic leader Nichirei, while in dried foods, investors are looking for new offerings beyond its Knorr brand soups.

The Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, and Brazil have become important overseas markets for Ajinomoto. But even there the company faces competition from local food makers and has seen profit margins shrink in the past decade.

“Ajinomoto needs to show a growth model for its food business, especially in overseas markets,” Daiwa analyst Morita said.

‘This campaign has to succeed first in Japan’

Ajinomoto aims to recast its food business under the umbrella of healthy eating. Its original seasoning, MSG, may be dismissed in some quarters—particularly in the US—as harmful, but the company says that not only is it safe, MSG is even good for health. Used as a partial replacement for salt, especially in meals that contain protein such as meat, it can reduce sodium intake, the company’s campaign argues.

Ajinomoto wants to make its brand synonymous with “less salt,” said Taro Fujie, general manager for food products. “This campaign has to succeed first in Japan. If it does, then it can be exported to other countries.”

Another campaign encourages people to consume more protein. Insufficient protein intake is a common problem among elderly people, Fujie said. Ajinomoto has released Prottie, a powdered soft drink with high protein content, in the Philippines and Thailand.

Also in Thailand, Ajinomoto’s popular canned coffee, Birdy, was originally intended for truck drivers who needed caffeine to stay awake on the road. It was very sweet. Today, Ajinomoto sells lower- or no-sugar versions to attract more health-conscious clientele including women.

“The wealthier you get, the more careful you become about the food you eat and your own health,” Fujie said.

Nakamura, the chemicals chief, said that Ajinomoto is comfortable having operations that span everything from powdered coffee to contract drug manufacturing to chip materials.

“We have a diverse range of businesses. That’s our strength,” he said.

For Daiwa analyst Morita, it is even simpler. Ajinomoto is a company based on amino acid technology.

“In some sense, Ajinomoto may be more a chemicals company than a food company,” he said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if the non-food segment comes to account for half its profit in the future.”

The article’s featured illustration was provided by Nikkei Asia. Created by Rie Ishii and Ken Kobayashi. This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.