As the coronavirus pandemic swept through Indonesia last year, the homebound population turned to e-commerce, first for survival, and then out of habit, for everything from daily groceries to financial products. One of these new converts was Meta Jayanti, a civil servant in the prosperous Javanese capital of Semarang.

Previously a loyal customer of Tokopedia — the e-commerce app she used to buy anything from face masks to instant noodles, delivered swiftly to her door every few days by motorbike — she gradually switched to its rival Shopee. The app boasted free delivery on some purchases and “a more varied product offering,” the 31-year-old said. She recently bought a study desk, something she couldn’t find on Tokopedia.

That led her to use ShopeePay, Shopee’s digital payments service, which gave huge cashback offers — sometimes as much as 30%. She now uses it more often than OVO, the digital payment service partly owned by Tokopedia.

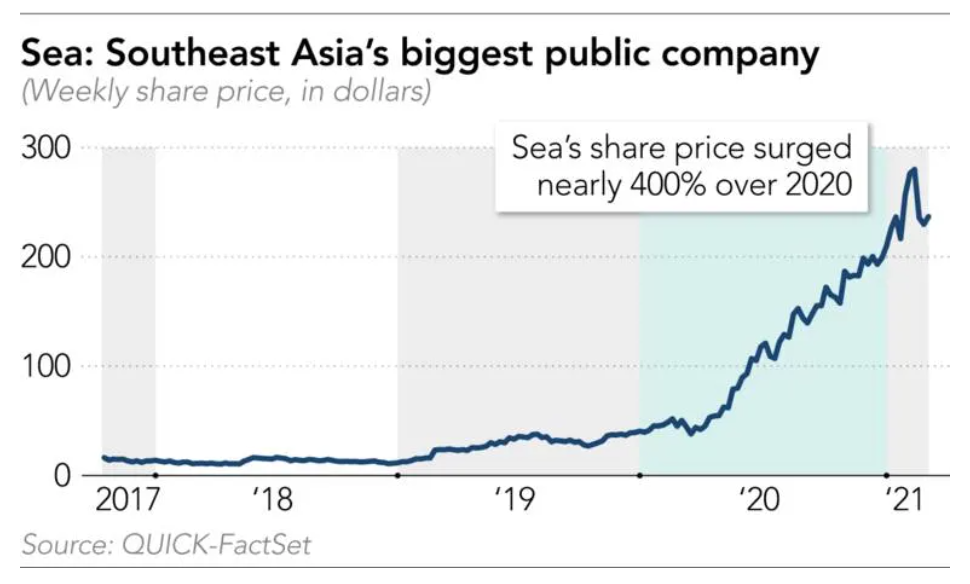

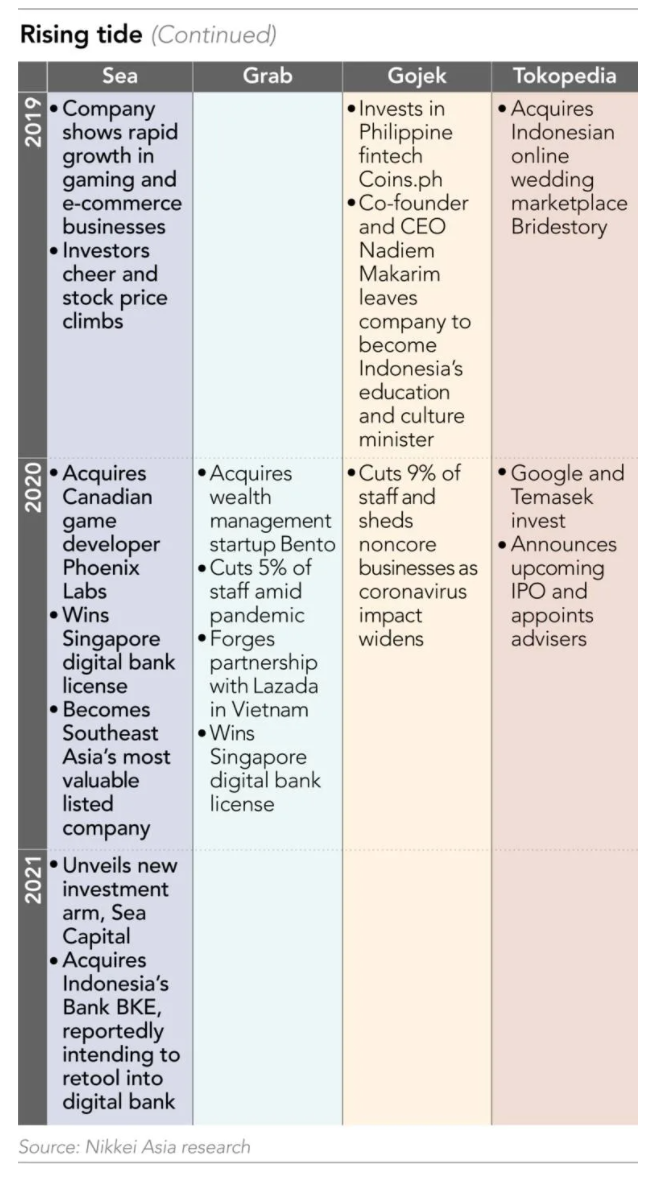

Jayanti was not alone. From relative obscurity in Indonesia’s tech landscape, Shopee has risen to become the country’s most visited e-commerce platform, according to digital research firm iPrice, and ShopeePay the most used digital payments service, according to Ipsos Indonesia. That has helped make Shopee’s parent, Sea Ltd., one of the most successful companies of the pandemic. Its New York Stock Exchange-listed share price rose 395% in 2020.

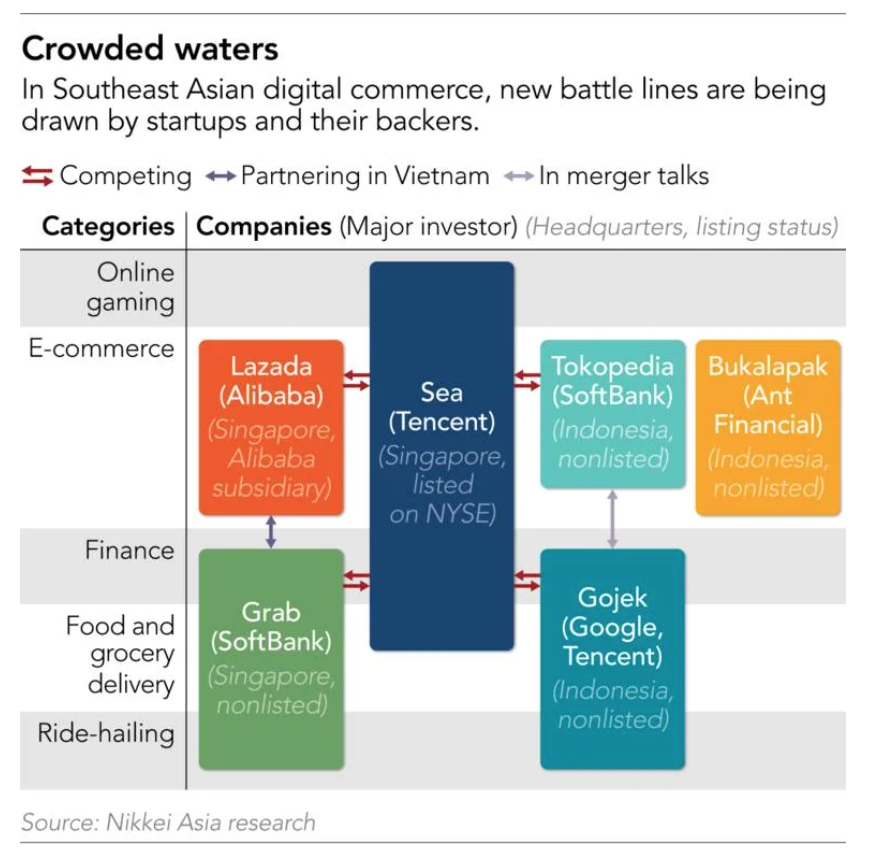

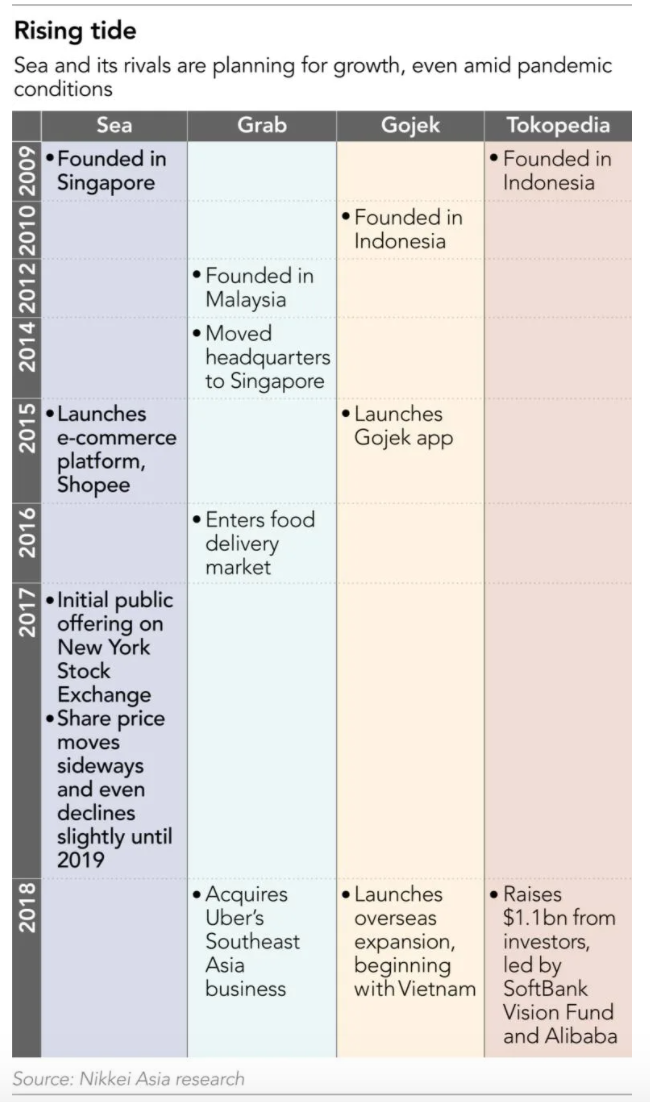

Before Sea’s emergence in Southeast Asia’s biggest market, the tech scene in Indonesia had been a tidy three-way competition between evenly matched unicorns — private companies with valuations over USD 1 billion — which dominated the sector.

There were Gojek and Grab, which started with motorbike taxis before quickly branching out to other services like food delivery and digital payments. Tokopedia, meanwhile, was one of the pioneers of e-commerce, helping to popularize the concept of buying and selling online. They allowed millions of informal workers to join a more structured market and earn more income.

But now, Singapore-based Sea is disturbing that placid status quo — not just in Indonesia, but across Southeast Asia. In Thailand and the Philippines, Shopee topped Alibaba Holdings-backed Lazada in monthly website visits in the second and third quarters of 2020 respectively, according to iPrice data.

Sea’s ambitions clearly go beyond e-commerce in Southeast Asia, Sachin Mittal, an analyst at DBS Group Holdings, told Nikkei Asia, adding the company was looking to extend its leadership there into other markets. Sea can also use its customer base to kick-start its expansion into fintech, he added.

The company made huge inroads into payments and e-commerce last year, while quietly moving into other areas like food delivery. Investors seem to believe that Sea can be all-conquering: The surge in its share price last year made the company the most valuable public entity in Southeast Asia. The stock seems to price in the likelihood that, one day, the entire region’s market will belong to it.

So rapid has been Sea’s growth that it is forcing rivals in the region to weigh up their options to compete against the Singaporean company’s onslaught.

It is a “Real Madrid problem,” said Hanno Stegmann, partner and director at BCG Digital Ventures, alluding to Spain’s most successful football club. “When you are in a strong position, everybody is attacking you, everybody wants to beat you.”

That has reordered the competitive landscape in Indonesia, where Sea is poised to walk away with the whole market. The country’s digital economy grew fivefold to USD 44 billion in 2020. Last year, Gojek and Grab put aside a legendary mutual animosity and began merger talks, which promptly fell apart. Now, attention is focused on talks between Gojek and Tokopedia.

Sea has one big advantage, however. It is publicly listed, meaning it can raise capital quickly and on a scale unimaginable to its privately-owned adversaries who must go back to their investors and arrange new funding rounds every time they want to raise more money.

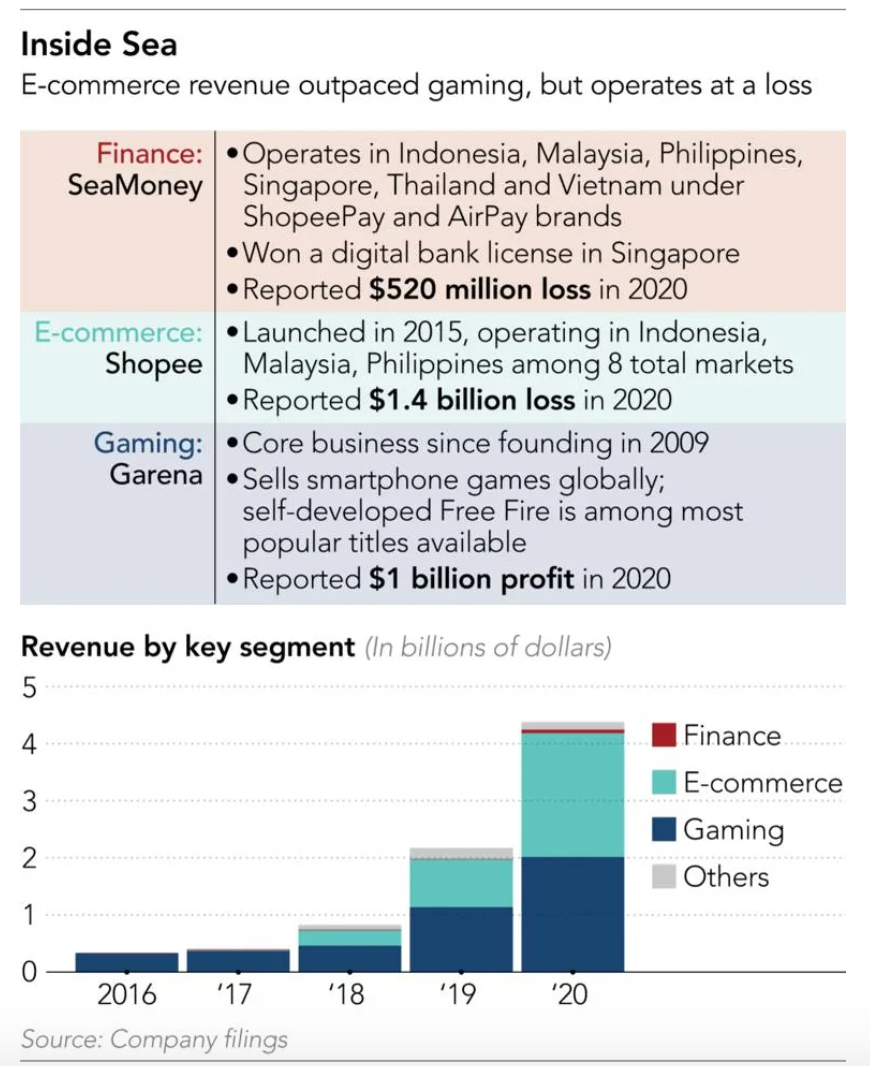

That access to funding, along with cash from its profitable gaming business, is crucial because aggressive promotion strategies have been part and parcel of Sea’s growth. The company offers free delivery and cashback on purchases, not to mention the usual promotions such as a chance to win a Mercedes-Benz in this year’s Chinese New Year promotion.

The sheer scale of Sea’s incentives, known as “cash burn” in the tech industry, is enormous. The company has made consecutive annual losses since at least 2017 when it went public, despite a ramp-up in revenue of several multiples. Last year, for example, Sea’s total revenue doubled to USD 4.37 billion, but the increase was eaten up by total expenses for sales and marketing which rose 89% to USD 1.8 billion, leading to a net loss of USD 1.61 billion.

The problem with such a strategy is not only that is it expensive, but it also may fail to win long term loyalty. Customers often end up following the money and not the brand. For example, Jayanti, the civil servant in Semarang, said: “If OVO starts to give bigger cashback, it’s very possible that I switch over from ShopeePay.”

One tech industry insider scoffed that Sea’s cash wasn’t buying market share, it was only renting it. “The way [Sea] are making inroads is through heavy promotion using their cash pile. They don’t have a massively strong brand equity,” the person said. Indeed, it is a strategy that Sea’s competitors also used before investors demanded a stop as they emphasized a path to profitability.

So far, however, the market approves of the strategy. Not only does Sea’s valuation of around USD 120 billion trump the valuations of regional tech rivals like Grab and Gojek by several multiples — both valued at USD 14 billion and USD 10 billion respectively, according to CB Insights — but it is by far the biggest public company in Southeast Asia, topping hitherto most valued companies such as Singaporean bank DBS Group Holdings and Thai state oil company PTT. Sea’s latest valuation is even higher than some of the best-known global U.S. tech stocks such as Uber, which was at USD 112 billion as of March 12.

Merger season

Sea shares benefited from several factors, not least of which is COVID-19. Its core businesses of gaming, e-commerce, and digital payments all took off due to the change in consumer habits during the pandemic. The company is also a rare case of a Southeast Asian tech company listed on a Western market, drawing interest from investors who are beginning to see the potential in a regional digital economy expected to be worth USD 309 billion in 2025.

The high valuation allowed Sea to raise nearly USD 3 billion in December with new share offerings that did not dent its share values significantly. “The liquidity — Sea’s [ability to] access capital — is too big,” said one investor in another company. Competing internet companies in Southeast Asia “must have the same playing field with Sea. Otherwise Sea is coming with food delivery, payments. They can [expand] everywhere,” the investor added.

Sea now controls a small Indonesian bank, setting it up to compete in internet finance — another field of potential competition with Gojek and Grab. And orange-jacketed drivers for ShopeeFood are an increasingly common sight in Jakarta since the company began its own food delivery service in Indonesia last year, quietly building it up to compete with the front-runners.

Forrest Li, Sea’s chairman and group CEO, founded the company in Singapore in 2009 as a gaming company called Garena. Early backers included China’s Tencent Holdings, which continues to be a major shareholder in the company. Garena launched its e-commerce arm Shopee in 2015, now the most visited e-commerce website in six countries it operates in, according to quarterly data from research firm iPrice. Garena changed its name to Sea in 2017.

E-commerce revenues exceeded that of gaming in 2020, but its gaming business, the only profitable arm under the company, continues to be the cash cow, with proceeds used to fund the growth in its other core businesses.

Garena reported an operating profit of USD 1.01 billion in 2020, up 92% from 2019, backed by its smartphone game Free Fire. First released in 2017, the battle royal game is now played in more than 100 countries across the world, popular in some of the world’s most populous countries like India, Brazil, and Indonesia. Due to its popularity, the game is expected to generate a steady flow of cash for the company at least for the next few years. That gives it further ammunition for funding its e-commerce and fintech growth.

Read more: In the top flight: Everything you need to know about Traveloka (Part 1 of 2)

Faced with Sea’s emergence and its cash-laden war chest, tech companies in the region are realigning their battlefronts and drawing up plans to compete with the Singaporean company, including speeding up their IPO plans.

Gojek and Grab, perennial rivals that have long competed for dominance in Southeast Asia in ride-hailing, food delivery, and payments, began merger talks a year ago. Investors on both sides dreamed a future where they could gain a significant windfall from an IPO of the merged entity, banking on the fact that Sea has firmly put Southeast Asian tech companies on the radars of Western investors.

“I think all the investors [in Gojek and Grab] are thinking that Grab is [valued at] USD 14 billion, Gojek is USD 10 billion. Let’s combine and list, maybe we can go USD 50 billion,” said an investor in Grab at the time talks were active. “Sea is USD 100 billion. I think ultimately if we can be half of that [it’s a win].”

A merger between the two entities seemed unthinkable during the height of their rivalry, so toxic was their competition. In public forums, executives from both companies would sometimes not deign to mention the other’s name, instead referring to “our rival.” In the background, people from both companies would boast how cash-prudent they were compared to each other. Nadiem Makarim, co-founder of Gojek and now Indonesia’s education minister, said in 2018 when Gojek expanded to Vietnam that the reason both companies had similar services was that Grab “keep[s] copying us.” Grab “consistently outspends us [but is] not able to actually threaten us in any existential way,” was his take on their competition at that time.

Both companies began merger talks in February last year, borne out of the need to cut back on competition to reach profitability quicker and stop burning money — said to be USD 40 to USD 70 million a month, at least initially. While the first talks happened prior to Sea’s rise, the negotiations gained momentum after pressure from investors who were beginning to witness the rapid rise in Sea’s share price.

Talks ultimately collapsed around the end of last year as both companies could not come to an agreement on the shareholding ratio of the combined entity. One person with knowledge of the negotiation said that Gojek demanded 40% control of the merged entity, something Grab was not willing to play along with. The Singapore-based company was adamant that it could contribute significantly more to the combined entity’s profits, and hence 40% was asking too much.

Gojek has since switched its potential partner and is now in talks with Tokopedia, a direct competitor to Sea, valued at around USD 7 billion. Combining the Indonesian startups makes sense because “they complement each other,” said one person with knowledge of the matter. A Gojek-Grab merger would get rid of competition in markets like ride-hailing and food delivery, but they are a low entry-barrier business, said the person, with potential for new competitors to challenge them.

“But Gojek and Tokopedia [together] is one plus one becoming 11,” he said. “Ride-hailing and food delivery are services that people use often but don’t spend that much money on. On the other hand, e-commerce is a service that people don’t use that frequently compared to ride-hailing and food deliveries, but tend to spend more money on. [A merged company would] cover the range of transactions,” the person said.

Unlike the talks with Grab, negotiation with Tokopedia is going smoothly, according to a person with knowledge of the matter. “It’s nothing like [the Grab talks]. The teams are working together, and everything is fairly harmonious. Everything is collaborative,” the person said. “Everybody was obsessed with Gojek vs Grab, but that is not a thing now” the person added, “the Grab comparison is not relevant now.”

Both companies are looking to conclude talks by around the end of the first quarter of this year, and then go public in both the U.S. and their home market of Indonesia. Masayoshi Son, CEO of Japan’s SoftBank Group which invests in both Grab and Tokopedia, previously supported the Gojek-Grab plan, but is now said to have thrown his weight behind the Gojek-Tokopedia deal.

“The date [of merger and IPO] is dependent on details, but everybody wants to do it as soon as possible,” said another person familiar with the matter. A valuation of USD 35 billion to USD 40 billion has been mooted.

And it’s not just the two biggest Indonesian tech companies that are accelerating their plans to go public. Traveloka, Indonesia’s travel booking unicorn, said recently that it is ready to list in the US this year, while another of Indonesia’s unicorns, popular e-commerce platform Bukalapak, was also recently reported as weighing up a US listing.

Both companies are examining the possibility of using a special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC. This is essentially a blank check: Sponsors raise capital by listing it, and then look for companies to acquire or merge with, offering the target company a way to go public more quickly than through a traditional initial public offering.

“I think right now, it makes a lot of sense for everyone to go public,” said an investor. “This window will not last forever, and if you miss this, it will take a while for the cycle to come back. It is a good time for everyone to list.”

It’s a window that Grab isn’t willing to miss either. The company had been exploring options to go public for a while, one option being the IPO of a merged Grab-Gojek entity. Now that the plan has been ditched, it is considering a US listing through a merger with a SPAC under Altimeter Capital Management, according to some media reports. This would value the company between USD 35 billion and USD 40 billion. Shares in Altimeter’s two SPACs both jumped after the report, reflecting investors’ expectations over the deal.

It’s a road that will more likely put Grab on a collision course with Sea. Founded as a taxi booking app and a game publisher respectively, they were not direct competitors, but as both companies expanded their fintech services — and for Grab, grocery delivery as well — their business verticals gradually overlapped.

The main battleground looks to be in the field of fintech, with both companies set to launch their digital banks in Singapore in early 2022. They were the only companies that were awarded a “full digital bank” license in the city-state, with a view to targeting underserved individual borrowers and depositors as well as small and medium-size enterprises. Singapore’s market is already highly saturated, but they eye replicating the digital banking business model in other Southeast Asian nations, where they see huge opportunities in bringing millions of underbanked people onto their platforms.

In Indonesia, Sea gradually built up its stake — albeit indirectly — in a small Indonesian lender Bank Kesejahteraan Ekonomi, better known as Bank BKE, last year, and now has majority control. Grab, on the other hand, partially owns OVO alongside Tokopedia, which has strong ties to Nobu Bank, banking arm of local conglomerate Lippo Group which is also a shareholder in the digital payments company. Gojek has also latterly joined the game, acquiring a 22% share in another local lender, Bank Jago.

Grab, with its total revenue having returned to pre-coronavirus levels, according to its president Ming Maa, is set to focus on the more promising fintech and food delivery segments, gradually moving away from ride-hailing. The company recently raised USD 300 million for its financial business unit.

In deliveries, the company expanded GrabMart, an on-demand grocery delivery service across the region, through partnerships with convenience stores and other retail shops. It also put pen to paper in November on a partnership deal with Lazada in Vietnam, which allows Grab drivers take delivery jobs for Lazada’s e-commerce operations in the country. Consumers can also now access Grab’s food delivery service via Lazada’s app.

This partnership would help Grab better compete with Sea in Vietnam. For Grab, Vietnam is the only market in six major Southeast Asian countries where it does not have the top share in food delivery, according to a report on the region’s food delivery industry from Singaporean consultancy Momentum Works. The No. 1 food delivery in Vietnam in 2020 was Now, operated by Sea group company Foody, which controlled a 42% share in the country versus Grab’s 40%.

Territorial clashes

Sea is not resting on its laurels either, with the company paving the way for further expansion. Its latest move came in the form of Sea Capital, a new investment arm it announced earlier this month. Sea launched the unit through an acquisition of Hong Kong-based investment firm Composite Capital Management, led by David Ma, a longtime investor of Sea. Sea will allocate $1 billion in this unit for new investment in tech companies over the next few years.

“By investing into the growth of our broader ecosystem, we believe Sea Capital can help accelerate the growth of the overall digital economy and create real and lasting value for our users, business partners, and the community,” Sea CEO Li said during the March 2 press conference.

Sea will also build an artificial intelligence laboratory under a newly assigned chief scientist. The lab intends to develop “insights and technologies related to its existing businesses and new opportunities beyond,” according to Sea. The chief scientist, Yan Shuicheng, is an expert in AI, with a particular focus on computer vision, machine learning and multimedia analysis, according to the company.

Meanwhile, the company is quietly exploring new markets beyond Southeast Asia. It is expanding its e-commerce business in Latin America’ biggest economies such as Brazil — where it already has established management on the gaming business — although e-commerce in Latin America is “preliminary” for the company and it “needs to observe the markets,” said Sea’s chief corporate officer Wang Yanjun.

Yet, for all its growth, Sea’s great strength — the ability to tap the public market — could be one of its greatest liabilities.

Sea is still losing money with its expensive promotions, a fact that could weigh against them in the near future, according to Jeffrey Funk, independent technology consultant and former associate professor at the National University of Singapore.

Sea’s losses as a percent of revenues fell from two-thirds before the pandemic to one-third in the second half of 2020, he said, adding that this offering a glimmer of hope for a profitable future. “But one-third is still a long way from profitability, particularly when lower losses mostly came from a lockdown-fueled doubling in revenue in 2020,” he said. “The question is: How long will investors ignore losses?”

“The downside [of being public] is, you are much more of a subject to volatility, you are much more under scrutiny,” said Stegmann of BCG Digital Ventures. “Sea is an interesting example. … When a quarter is not going well, the big advantage of having access to capital markets can suddenly turn into your stock price declining a lot, and access to capital markets suddenly shut or become difficult, or interest rates for your bonds increase overnight,” he said.

It’s a problem that won’t go away anytime soon. The disadvantage of Sea’s cash-burning approach is that customers who are lured in by fat promotions are unlikely to stay loyal. Once Sea’s money runs out, someone else’s money will win the day.

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.