This story originally appeared in Open Source, our weekly newsletter on emerging technology. To get stories like this in your inbox first, subscribe here.

Skyscrapers, road networks, and urban transportation systems—our cities are marvels of modernization, constantly growing and evolving. But they are typically not designed with everyone in mind. All too often, a one-size-fits-all approach is taken when it comes to urban planning, paradoxically influencing how life is experienced in different ways. For individuals with disabilities, this translates into navigating a tapestry of urban spaces replete with inaccessibility. And that’s a problem.

In societies that strive to be inclusive, it’s fair to expect everyone to be afforded an equal shot at building and living an independent life, regardless of disability. But achieving this is easier said than done. Mobility is by far the most major of issues. For people with visual disabilities, a lot more is felt rather than seen, and that generally necessitates the use of auxiliary tools and facilities to assist them in navigating their surroundings.

A common method used to help the visually impaired become more mobile is tactile paving. This refers to the paving of textured surfaces that assist people with visual disabilities in making sense of their proximate environment, thereby providing them with the means to travel independently. Tactile paving originated from Japan and has since become widely adopted all around the world.

Please make way

For something that has been utilized for decades, tactile paving is ironically not a great standalone solution. In an interview with The World of Chinese, Sissi, who’s visually impaired and lived in Beijing for two years, said that the solution has limited effectiveness due to the indifference of others. Specifically, she singled out individuals who view these pavements as “convenient parking spots” rather than aids for the visually impaired.

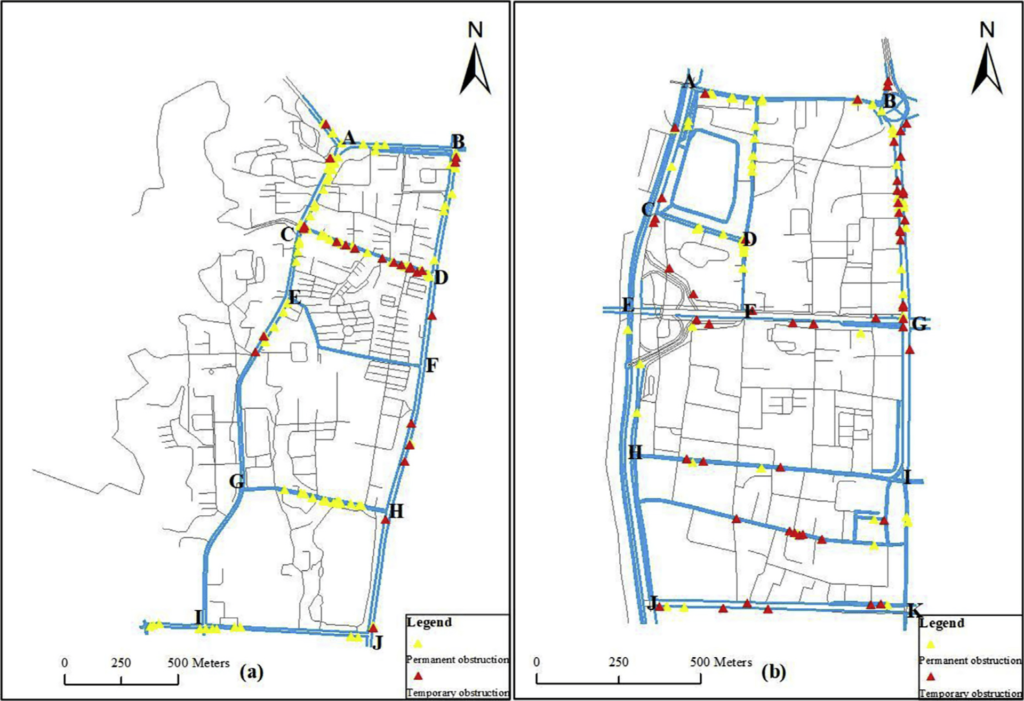

Sissi’s experience is hardly anomalous. In 2019, a study of the tactile paving network in Changsha revealed obstructions as a critical factor. When tactile paving surfaces are obstructed by objects, users are forced to go off track—an action that disrupts the wayfinding process. The possibility of facing such situations can also impose a mental load that may discourage them from traveling on their own.

Chen Jing, another interviewee from Guangzhou who spoke with The World of Chinese, echoed Sissi’s sentiments, adding that tactile paving also confines movement to a single direction, which can complicate more intricate maneuvers such as detours.

It’s worth noting that Sissi and Chen’s experiences are not unique to China, but also common to other countries like Singapore. What their experiences do reflect, however, is the ableism inherent in but generally unintended by society. More importantly, the continuance of tactile paving—which dates back to the 1960s—should be interpreted not as a compliment to its efficacy, but rather the lack of progress made with mobility solutions for people with visual disabilities.

This situation appears more precarious when we consider how fast technology has advanced in recent years. While everyone is seemingly fixated on the next big thing, such as generative artificial intelligence or Web3, little attention has been paid to support the visually impaired. Beyond tactile paving, available solutions are limited and mostly rely on audio commands and feedback to aid in predefined scenarios. It’s hardly ideal.

Braille me out

So, if tactile paving alone doesn’t make the cut, you might be wondering, what would?

In 2021, a new sight began to unfold in the subway stations of Busan, a city situated along the southern coastline of South Korea:

Dubbed as “barrier-free” kiosks, they were introduced as part of the 2021 Smart City Challenge, a project hosted by the South Korean ministry of land, infrastructure, and transport. Their intended purpose? To provide navigation services to all passengers, regardless of disability.

Next to the screen of the kiosks is a tactile pad that doubles up as a “display” by utilizing patented actuator technology of Dot Incorporation, a South Korean company seeking to redefine mobility for the blind and visually impaired. In contrast to traditional braille that’s static in nature, Dot’s technology utilizes dynamic braille cells that are electromagnetically controlled, enabling the production of tactile displays that can output varying combinations of braille to achieve a variety of purposes.

These kiosks are operated using a set of braille-labeled controls, accompanied by voice guidance to assist the user in selecting a desired destination. Once a destination has been chosen, the system renders a “map” of the optimal route in braille on the tactile pad.

Dot’s kiosks stand out not only for providing an alternative means of wayfinding for the visually impaired, but also because it offers a more native approach. Braille holds immense significance for the visually impaired community and can be metaphorically likened to the way sighted individuals perceive the world visually.

Rather than translating visual information into audio, receiving a detailed sequence of directions expressed in braille and experienced through touch is likely to be more effective than listening to an extended series of audio explanations, which could lead to more confusion than assistance.

Navigating the “phygital” era

With cities expanding not only physically but also into virtual realms, the concept of mobility is taking on a new dimension that further complicates the plight of the visually impaired.

Adapting to the digital world can be a daunting prospect for those without sight. While sighted individuals can grasp complex concepts through visual information, people with visual impairments have hitherto relied on traditional solutions like tactile books, which are expensive and rare, and audio content, which may fall short in conveying intricate subjects.

Last year, Dot unveiled the Dot Pad, a handheld iteration of the tactile pad integrated into the kiosks. This device can present visual content haptically and in braille by leveraging AI to analyze and segment images for the most precise display.

What sets the Dot Pad apart is its capability to unlock new categories of content that were previously inaccessible to the blind and visually impaired, including games, comics, movies, and more.

Dot is actively working to advance the technology behind the Dot Pad and is currently collaborating with corporations, organizations, and governments from all around the world to widen its accessibility.

Develop it right, and the Dot Pad could usher in a new mobility paradigm for the visually impaired, enabling them to access virtually any content on the internet and comprehending them in real time by touch and braille.

This story mainly focused on the perspective of the visually impaired. To learn about assistive technology in other contexts, you can check out:

- Hearing-impaired individuals speak their “first sentence of life” using AI (by KrASIA Connection)

- Hearing it all: Q&A with Amy Zheng, Asian growth markets general manager of Cochlear (by Brady Ng)

- Vulcan Augmetics builds modular robotic prosthetic arms for amputees (by Khamila Mulia)