Between 2019–2023, about one in three Chinese startups received direct investment from state-owned capital institutions, according to internal data from Lighthouse Capital. Even in artificial intelligence, long considered the domain of USD-denominated venture capital funds, state-backed industrial funds in Beijing and Shanghai now lead the cap table.

“In today’s market, you can trace state capital to virtually every fund,” one state investor told 36Kr. He was only half joking.

Ji Xing, a partner at Lighthouse Capital, put it plainly:

“State-backed and government-affiliated limited partners (LPs) have become the primary funding source for RMB-denominated funds in China. From 2014–2023, their contribution jumped from 20% to 41%.”

Meanwhile, Fortune Capital managing partner Xiao Bing said:

“The fate of individuals, firms, and the entire venture capital industry is now more intertwined with that of the state than ever before.”

And yet, despite constant references, state capital remains poorly understood, often generalized, rarely unpacked.

That’s partly due to its sprawling, opaque structure. It comprises parent funds, guidance funds, and direct investment vehicles, stacked across national, provincial, municipal, and district levels. Entrepreneurs typically engage with local investment promotion officials, unaware that the funds may originate from local treasuries, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), or development and reform commissions. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) also pursue strategic investments spanning entire industrial chains. Some firms—such as Fortune Capital, Leaguer Ventures, and Oriza Holdings—operate nearly indistinguishably from commercial funds.

These investments usually stay under the radar. High-profile exceptions, such as Hefei’s bailout of Nio, make headlines, but most activities go unnoticed. Quietly but effectively, state capital has become China’s key counter-cyclical force, using its scale to stabilize the market.

Making a case for state capital

To understand its impact, it’s essential to first understand its purpose.

Through interviews with investors and advisors who regularly collaborate with state entities, 36Kr identified three defining traits that guide how state capital behaves:

- Policy alignment: Investments support national priorities and strategic sectors.

- Economic development: Capital deployment must boost local GDP, employment, and industrial capacity.

- Risk sensitivity: Decisions are shaped more by regulatory and risk considerations than financial returns.

Liang Sumin, partner at Inno Investment Bank, explained:

“State-backed investments usually come with strings attached: employment, taxes, GDP, and fixed asset contribution calculations. The accounting is even stricter than in market-driven funds. Many decisions require sign-off at the ‘secretary-level meeting’ which serves as a checkpoint for weighing both risks and outcomes.”

In short, state capital must balance returns, risk, and regional development goals.

Two decades ago, China’s venture capital market revolved around rapid growth and overseas exits, often driven by foreign capital. That model has shifted. This isn’t about state replacing private. It’s about public capital coordinating with industrial and financial forces to create a new growth engine.

Still, the shift has generated friction. The hybrid nature of state capital has drawn skepticism, especially around inefficient fund promotion and risk aversion. But recent policies aim to address exactly those issues.

- On April 30, 2024, the Politburo introduced “patient capital” as a directive to “develop new productive forces tailored to local realities.”

- On August 1, 2024, China enacted a fair competition review regulation, banning selective subsidies and preferential tax treatment for specific companies.

- On January 7 this year, Beijing released guidelines to promote the high-quality development of government funds, calling for extended performance review timelines, flexible exit options, and an end to setting up funds solely for investment promotion.

- Shenzhen went a step further. In a draft policy for 2024–2026, it proposed cultivating what it termed “bold capital.”

These measures collectively refine the definition of state capital’s role: not as a market leader, but as a stabilizing force that directs resources toward long-term transformation, innovation, and sustainable productivity.

Since late 2023, government fund professionals have become more discerning. “Investment officers used to only care about hitting land-use targets,” said one advisor. “Now they ask about product-market fit.”

Liang from Inno noted another shift: a rise in direct investments. “In the past, 20–30% of state capital went straight to startups. The rest flowed through parent and guidance funds with varying mandates. That’s changing,” he said. In Beijing, some direct investment funds now operate hybrid models to spread risk and professionalize operations.

Over the past six months, 36Kr conducted an exhaustive survey of active state capital platforms in cities across China. With help from Inno, Lighthouse Capital, 100Summit Partners, Nebula Advisors, Taihe Capital, and data providers like Tianyancha and Qichacha, the report seeks to answer one central question:

What makes a well-functioning model of state capital investment?

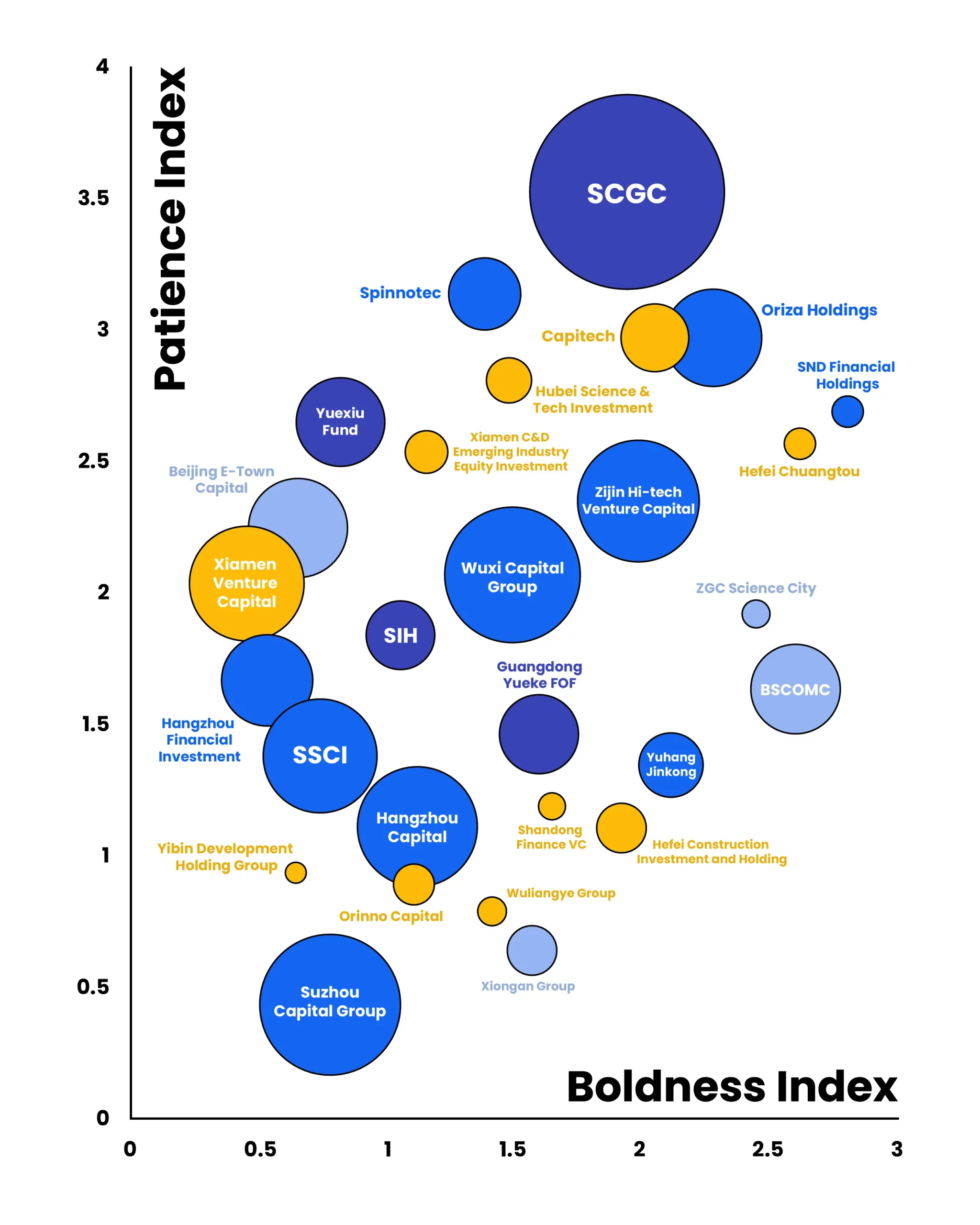

The report introduces two core metrics:

- Boldness index, to measure early-stage activity, direct investments, and partnerships with market general partners (GPs).

- Patience index, to evaluate longevity, consistency, and resilience across cycles.

Due to fragmented and opaque data on local funds, this snapshot may lag behind real-world developments. Still, it offers rare insight into the mechanics of state capital in China.

Policy roots run deep

From the beginning, national policy has been the driving force behind China’s push to channel state capital into equity investment.

The origins trace back to 1988, when Beijing established six national-level investment companies as part of a broader effort to reform the country’s investment system. Around the same time, provincial and municipal governments began setting up local investment companies. But it wasn’t until 2003—when the SASAC system was introduced—that state investment entities began to proliferate in earnest.

Following the Asian financial crisis, China entered a new phase of economic growth. Concerned about overheating, central authorities moved to curb large-scale investment. In response, local governments turned to state-owned investment companies as a workaround, allowing them to continue funding infrastructure projects without breaching macroeconomic controls. By 2008, when China launched a RMB 4 trillion (USD 560 billion) stimulus in response to the global financial crisis, these entities had become key vehicles for directing capital into public works. Even fiscally modest counties formed such platforms, swelling their numbers nationwide.

Meanwhile, China was quietly laying the legal foundation for what would later become its government-guided fund system. Starting in 2005, a series of regulations took shape—covering venture investment enterprise rules, partnership structures, and exemptions from state equity transfer requirements for SOE-backed funds.

But the real inflection point came in 2014—not through policy directives, but a shift in accounting rules. As economist Lan Xiaohuan wrote in his 2021 book Embedded Power: Chinese Government and Economic Development, revisions to the Budget Law prohibited local governments from hoarding unspent subsidies and tax breaks. Funds left idle for more than two years could be clawed back by higher-level authorities. Faced with a use-it-or-lose-it constraint, local governments urgently needed new deployment tools. Guidance funds filled that gap.

Together, state-owned investment companies and guidance funds emerged as the two foundational pillars of China’s institutional capital. Those that established early positions—and aligned with favorable policy mandates—gained a clear edge in scaling up.

In its review of today’s most active platforms, 36Kr found a recurring theme: many are embedded within high-tech parks, economic development zones, or newly established national-level zones. These locations often grant them wider investment mandates and deeper policy support.

Proving the playbook

Founded in February 2009, Beijing E-Town International Investment & Development, commonly known as E-Town Capital, is the investment arm of the Beijing Economic-Technological Development Area (BDA). As of June 2024, it manages RMB 123 billion (USD 17.2 billion) in total assets, with a mission centered on advancing industrial development and technological innovation within the BDA.

Established in 1994, the BDA is Beijing’s only national-level economic development zone. Its mandate: attract high-end manufacturing and tech-driven projects to modernize the capital’s industrial base. That directive continues to shape E-Town’s investment strategy today.

In its early years, the fund operated primarily as an investment promotion tool. Just six months after launch, it contributed 370,000 square meters of land to finance BOE Technology’s 8.5-generation LCD production line. By 2015, E-Town had exited its BOE stake, recovering RMB 5 billion (USD 700 million). The project catalyzed the formation of Beijing’s digital TV manufacturing cluster, drawing in suppliers like Corning, TPV, and Sumitomo. The park now generates over RMB 100 billion (USD 14 billion) annually and employs around 20,000 people.

From 2012 onward, E-Town pivoted toward semiconductors, building a supply chain hub in northern China. Its approach has spanned equity rounds, strategic acquisitions, and consortium-led joint ventures, including:

- RMB 700 million (USD 98 million) to expand SMIC’s wafer fab.

- Joint takeovers of US chip firms OmniVision, ISSI, and iML.

- RMB 4 billion invested in Yandong Microelectronics alongside the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund (ICF).

- A RMB 16.1 billion (USD 2.25 billion) joint venture in 2022 to establish Changxin Memory Technologies.

The result is a dense semiconductor cluster anchored by SMIC, BOE, Yandong, Changxin, and Naura Technology. Notably, the BDA now hosts all the core subsystems required for China’s domestic lithography machines, including light sources, objective lenses, and wafer stages.

E-Town Capital has also made bold moves in the automotive sector. In 2010, it teamed up with AVIC Automotive Systems to acquire US-based Nexteer Automotive for USD 480 million. In 2013, it committed RMB 1 billion (USD 140 million) to a Mercedes-Benz factory in Beijing, later joining BAIC Group’s IPO with a USD 100 million cornerstone investment.

Recent bets align with the rise of electric and autonomous vehicles. The fund has backed projects involving Huawei, Xiaomi, PhiGent Robotics, and SemiDrive. By 2023, the automotive sector within the BDA had grown to generate over RMB 200 billion (USD 28 billion), roughly 60% of Beijing’s total output in the field. Today, the zone is home to more than 120 smart vehicle companies and hosts three national R&D platforms.

As of mid-2024, E-Town Capital had supported over 200 projects with cumulative investments exceeding RMB 100 billion. It now functions as a “chain master,” coordinating policy alignment and capital flows across verticals. Its portfolio partnerships include national funds such as the first and second phases of the ICF, initiatives for manufacturing transformation, and a web of co-GP and M&A vehicles spanning biomedicine, telecommunications, and more.

Building up from scratch

In April 2017, China officially launched the Xiongan New Area in Hebei, designating it the country’s third national-level “new area” after Shenzhen and Shanghai’s Pudong. Three months later, China Xiongan Group was established with an initial registered capital of RMB 30 billion (USD 4.2 billion). Its mission: to oversee the transformation of Xiongan from farmland into a model city for innovation, sustainability, and governance.

By 2024, the group had registered eight funds with total assets of roughly RMB 15.7 billion (USD 2.2 billion). Its flagship vehicle was launched just a year after the area’s inception. Planned at RMB 10 billion (USD 1.4 billion), the fund allocated RMB 9 billion (USD 1.26 billion) to ecological protection in the Baiyangdian lake region, and RMB 1 billion to facilitate the relocation of central SOEs from Beijing to Xiongan. Since then, smaller funds have been created to support green construction and infrastructure projects.

After five years of low-profile development, Xiongan’s state capital arm began publicly detailing its progress in 2023. According to Han Wei, head of legal affairs at Xiongan Group and executive director of its fund division, the group’s investment focus centers on cultivating strategic industries. Five key sectors have been designated as anchors for Xiongan’s industrial development: new materials, next-generation IT, biotechnology, modern services, and ecological agriculture.

As of early 2025, Xiongan Group had launched ten funds with a combined registered capital of RMB 22 billion (USD 3.1 billion).

Given the area’s elevated policy status, a central goal is relocating the headquarters of key SOEs. In 2024 alone, Xiongan attracted 40 new SOE subsidiaries. Nearly 300 SOE-affiliated entities now have a footprint in the zone.

This context gives particular weight to Xiongan’s RMB 1 billion “SOE relocation fund,” designed to facilitate mixed-ownership reform and equity diversification among SOEs shifting operations from Beijing. Public records show the fund has already backed firms such as CSCN and China Mobile’s Xinsheng Technology.

Tech is the mandate

If equity investment is the vehicle, technology is the engine.

For China’s state capital, tech innovation isn’t just a preferred direction. It is the raison d’être. That conviction dates back to 1985, when Beijing issued a directive urging more support for high-risk, fast-moving science and tech enterprises. Just six months later, the State Council approved the establishment of China’s first venture capital institution, co-founded by the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Ministry of Finance.

The model caught on quickly. In 1992, the Shanghai municipal government formed the Shanghai STVC Group to tackle the challenge of commercializing research from China’s reform era. A year later, it launched a joint-stock venture platform and partnered with US-based IDG to form Pacific Technology Venture Investment Corporation, the country’s first sino-foreign VC firm. It eventually evolved into what is now IDG Capital.

These early ventures laid the groundwork for two decades of rapid growth. The concept was straightforward yet powerful: mobilize public capital at both the national and local levels to accelerate the commercialization of science and the upgrading of industrial capabilities.

Data from China’s asset registration platforms shows a steady rise in funds labeled with terms like “results,” signaling a growing emphasis on applied science and technology. As of 2024, the number of such funds reached an all-time high.

To understand how state capital fuels tech innovation and early-stage venture activity, 36Kr categorized leading players into four distinct types:

- Regional and integrated services groups, which are entities that combine local governments, research institutions, capital, and major tech companies into comprehensive platforms for applied R&D and commercialization.

- Angel fund-of-funds (FOFs), typically backed by municipal governments, are small funds that focus on small, early-stage, and tech-heavy investments. Their goal is to derisk early innovation and crowd in private capital.

- Incubators and accelerators, backed by the government or institutions, are platforms that manage incubation and commercialization of research-stage projects.

- Local industry and research institutes, which serve as pilot-scale R&D platforms with varying degrees of commercialization capability, acting as bridges between lab research and industrial application.

Zhongguancun: Where science meets startups

In the Haidian district of northwest Beijing, dozens of tech startups are launched every day. This is Zhongguancun Science City—the centerpiece of Beijing’s international innovation corridor and home to some of China’s most renowned institutions, including Peking University, Tsinghua University, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. It also hosts a who’s who of the tech world, from ByteDance and Didi to Xiaomi, Baidu, Megvii, and Lenovo.

The ecosystem here is dense, diverse, and highly integrated. Alongside universities and corporate headquarters are startup incubators, patent firms, venture capital offices, and global R&D centers. It’s a blueprint for what a truly collaborative innovation district can look like.

In 2019, the Haidian district government established Zhongguancun Science City Innovation Development Company with an initial capital of RMB 6 billion (USD 840 million). Fully owned by the district’s state capital arm, the company is structured around three fund families: technology innovation funds, growth-stage tech funds, and government guidance funds.

Some of these funds predate the holding company itself, dating back as far as 2009. As of 2025, the guidance fund arm had directly supported 106 early-stage science startups and launched 47 sub-funds. Notable portfolio companies include Tinavi, Cambricon, Loongson, and Luster LightTech.

Since 2019, the growth-stage family has completed two phases of capital deployment, totaling over RMB 10 billion. These funds have backed a network of science-focused vehicles, including the Zhiyou Scientist Fund, a Sinovation Ventures-led science fund, and CAS Star’s second deep tech fund. They have also supported vertical-specific funds managed by Gaorong Ventures, Glory Ventures, The Jiangmen, and Alwin Capital.

Together, these vehicles form an expansive early-stage investment network focused on frontier technologies.

To date, the platform has made more than 50 direct investments. The first phase emphasized healthcare and semiconductors. The second expanded into AI, big data, next-generation IT, and smart manufacturing. Standout portfolio companies include Zhipu AI, DP Technology, ModelBest, Shengshu Technology, 4Paradigm, Unitree Robotics, and Galbot, as well as semiconductor firms like Moore Threads and Kunlunxin.

In February 2025, Zhongguancun launched the third phase of its growth-stage fund with a total scale of RMB 10 billion. The Haidian government increased its equity in the fund’s sole LP—Haidian State-owned Asset Investment Group—bringing its total commitment to RMB 9.9 billion (USD 1.4 billion).

Shenzhen’s seeding giants

Launched in 2018 by the Shenzhen municipal government, the Shenzhen Angel Fund of Funds (FOF) is a strategic, policy-driven vehicle designed to back early-stage venture capital firms. With a total fund scale of RMB 10 billion, its mandate is to support Shenzhen’s emerging and strategically important industries—including future-oriented sectors such as AI, biotechnology, and semiconductors.

Unlike commercial LPs, the FOF is not profit-driven. Its goal is to foster a more dynamic startup environment, particularly for companies with the potential to become the next Huawei or Tencent. To that end, the fund is willing to share carry, waive certain gains, or yield economic returns to co-investors to enhance fund competitiveness.

The FOF is run on a market-oriented basis through a joint venture between Shenzhen Capital Group (SCGC) and Shenzhen Investment Holdings (SIH). Together, the two entities vet general partners (GPs) with deep domain expertise and a long-term investment outlook.

As of April 2024, the Angel FOF had backed more than 80 sub-funds operating at the angel stage, collectively managing over RMB 20 billion (USD 2.8 billion) in capital. These sub-funds have in turn invested in nearly 1,000 startups, including 161 valued above USD 100 million and six unicorns exceeding USD 1 billion in valuation.

Its sub-fund portfolio includes some of China’s top early-stage investors, such as ZhenFund, Green Pine Capital Partners, Highlight Capital, and Innoangel Fund. Notable portfolio companies include Moffett AI and Cellbri, which are both still early in their funding journeys but showing promising traction in their respective verticals.

In 2023, the FOF launched a complementary initiative: a science and technology seed fund. Backed by RMB 2 billion (USD 280 million) from Shenzhen’s science and technology bureau, it is China’s first policy-driven seed fund to be supervised by a technology authority rather than a financial one. As of early 2025, it has already begun deploying capital.

Corporates as copilots

Established in 2014, the Shanghai Angel Capital Guiding Fund operates under the city’s Development and Reform Commission with a focused mandate: use public capital to de-risk early-stage innovation and attract greater private-sector participation in science and technology ventures.

The fund’s model is notably collaborative. Rather than simply allocating capital to existing VC firms, it actively partners with listed companies and research institutions to co-create sector-specific sub-funds. These include vehicles affiliated with firms like Fudan Microelectronics and Titan Scientific.

As of October 2024, the guiding fund managed RMB 3.5 billion (USD 490 million) and had approved more than 140 sub-funds. It had exited 27 of them, with a portfolio spanning over 1,400 companies—more than 70% of which were still in the startup phase at the time of investment.

The fund also plays a pivotal role in activating corporate venture capital. Sub-fund collaborations include the Taitan Heyuan Fund, which invests across the scientific services value chain, and Shanghai Healthcare Capital, which supports the commercialization of academic research from institutions such as Fudan University.

Beyond institutional partnerships, the guiding fund works closely with firms like Step Holdings and Plug and Play China to support ultra-early-stage tech ventures. Notable projects backed through these partnerships include Leading Optics, Noematrix, and Tanxu Technology.

The result is a system that does more than fund early-stage companies—it creates pathways for deep tech innovations to move from lab to market, helping ideas achieve real-world application and commercial viability.

From research to commercialization

Leaguer Ventures traces its origins to the late 1990s, when the Shenzhen municipal government partnered with Tsinghua University to establish the university’s local research arm. In 1999, that initiative spun out Shenzhen Tsinghua Technology Development Company—the precursor to what would become Leaguer Ventures.

By 2015, the project had matured into a broader platform. The research institute and its affiliated entities were consolidated under the Leaguer Group banner, transforming the operation into a national engine for tech commercialization. Today, Leaguer blends academic R&D, public policy support, and venture capital into a single integrated platform.

While Leaguer Ventures is ultimately overseen by SASAC, its real edge lies in how it channels the depth of Tsinghua University’s research base. The firm operates on two core pillars: delivering science and technology innovation services, and advancing strategic emerging industries.

Unlike conventional investment firms, Leaguer doesn’t just provide capital. It also builds and manages physical infrastructure—including state-level incubators and co-working labs—to accelerate the journey from lab bench to commercial product. Its footprint now spans a nationwide network of facilities designed to support this transition.

On the investment front, Leaguer invests both directly and through a network of sub-funds. It regularly co-invests with partners like Shenzhen Capital Group (SCGC), Green Pine Capital Partners, and Cowin Capital, collectively supporting a wide range of early-stage science and tech startups.

Crucially, Leaguer’s national presence enables it to connect local innovation nodes into a cohesive, cross-regional ecosystem. Its long-term vision is clear: transform academic breakthroughs into scalable, commercially viable technologies that power the next generation of Chinese industry.

Building value chains

Whereas market-driven funds often pursue high-return bets and fast exits, state capital typically serves a broader mission: building or reinforcing entire industrial value chains.

Unlike lean commercial VCs, state-backed investors must weigh local economic growth goals and national development mandates. Beyond identifying the next unicorn, their role is also to nurture or anchor the sectors that underpin regional economies.

Two standout examples come from cities not traditionally seen as innovation centers: Hefei and Yibin.

Hefei’s bet on technology

Once considered a relatively modest industrial hub, Hefei has emerged as a national model for strategic, high-stakes investment—an approach locals refer to as “invest to attract.”

In 2008, with just RMB 30 billion in annual fiscal revenue, the city made a bold move: investing RMB 17.5 billion (USD 2.5 billion) into BOE to bring its sixth-generation LCD panel plant to Hefei. At the time, China’s display panel industry was heavily reliant on imports, and although BOE had the technical capacity, it was financially fragile from struggling against foreign dumping.

Hefei Construction Investment Holding (HCIH), then a conventional investment platform, devised a novel structure. It provided capital with a clause requiring BOE to buy back equity once strategic investors came onboard. In return, BOE agreed to root its supply chain in Hefei.

The gamble paid off. After production launched, domestic panel prices dropped 30%, disrupting Japanese and South Korean dominance. The project drew more than 300 suppliers including giants like Sumitomo and Corning, turning Hefei into a full-spectrum display technology hub. By 2023, the local display sector was generating over RMB 200 billion, accounting for 10% of global output.

In 2020, Hefei placed another high-risk bet: a RMB 7 billion (USD 980 million) rescue investment in Nio, then teetering on collapse. The deal came with firm targets, including annual vehicle sales of 500,000 by 2024.

Once again, the risk delivered. Nio relocated its China headquarters to Hefei, built a new factory with 1 million units of annual capacity, and attracted a surge of suppliers spanning battery producers, BMS firms, and component makers. By 2023, Hefei’s new energy vehicle (NEV) sector was generating RMB 300 billion (USD 42 billion), contributing over 10% of national output.

Behind the scenes, Hefei’s strategy blended boldness with discipline. In a televised interview, HCIH chairman Li Hongzhuo said that Nio’s rescue unfolded across four tightly coordinated workstreams:

- Technical and market due diligence with outside advisors.

- Policy alignment for electric vehicle incentives and battery-swap infrastructure.

- Comprehensive legal and financial reviews.

- Deep commercial negotiations.

In 2021, Hefei also invested RMB 2.2 billion (USD 308 million) in optics firm Ofilm to shore up a critical link in the supply chain.

It all began with a daring bet on BOE—a deal that yielded RMB 20 billion in returns and set the stage for a new wave of investment into semiconductors and AI. Today, Hefei is widely recognized as a rare case where municipal capital has come to embody strategic foresight.

From liquor and coal to battery powerhouse

In the late 2010s, the inland city of Yibin in Sichuan stood at a turning point. Long associated with liquor and coal—industries locals dubbed the “black and white” economy—Yibin was grappling with stagnating growth and an accelerating brain drain.

By 2018, liquor still accounted for 55% of the city’s industrial profits, and no viable new growth engines had emerged.

Meanwhile, China’s EV sector was gaining momentum. Spotting a narrow window of opportunity, Yibin chose to go all in on power batteries, despite having no prior footprint in the sector.

Its state capital platform, Yibin Development Holding Group, led the charge with a multi-pronged strategy:

- Industrial logic: Sichuan holds 57% of China’s lithium reserves. Yibin’s location along the Yangtze River offered low-cost waterborne transport—40% cheaper than road freight. The nearby Xiangjiaba hydropower plant supplied abundant green electricity, at costs roughly 30% below those in eastern China.

- Capital leverage: The holding group raised RMB 30 billion via a matrix of industrial funds. It partnered with top-tier institutions like IDG Capital and China International Capital Corporation (CICC), bringing credibility and investment-grade rigor to the initiative.

- Execution: In a nationwide bidding war to land battery giant CATL, Yibin committed to delivering 165 acres of industrial land within just 81 days. The effort was personally overseen by the city’s Communist Party secretary and organized via a “chain master” task force.

To deepen the ecosystem, Yibin’s largest SOE, Wuliangye Group, pledged RMB 13.6 billion (USD 1.9 billion) through an industrial fund to back CATL’s supplier network, creating a tight loop between anchor and downstream partners.

The outcome was transformative. Yibin established a “1+6” industrial cluster: one central zone in the Sanjiang New Area and six satellite parks. These zones attracted more than 120 battery-related companies. Changjiang Industrial Park focused on separators, Luolong on copper foil, and Gongxian on anode materials. Collectively, they form a 580-acre battery manufacturing hub. Major players like Kedali and Dynanonic soon followed.

Wuliangye, too, stepped beyond its legacy business. Through its industrial fund, it supported emerging projects like Tyeeli and SunSync.

The results came fast. From a standing start in 2019, Yibin’s battery output surpassed RMB 100 billion by 2023. Today, the city produces one in every seven power batteries globally, cementing its place as a heavyweight in global EV supply chains.

Equally significant: the boom brought talent back. What began as a high-risk public investment strategy evolved into a sweeping industrial reinvention.

The fragmentation fallout

As state capital expanded across China, so did a new wave of structural challenges. Chief among them: redundancy and fragmentation.

Starting around 2020, nearly every major city launched large-scale industrial fund clusters, with capital pledges routinely topping RMB 10 billion. The language in press releases was almost identical: “cover the entire industry chain,” “nurture innovation ecosystems,” “build a RMB 100 billion fund matrix.”

But as the headlines piled up, so did confusion. For entrepreneurs and GPs on the ground, navigating these overlapping fund networks often led nowhere.

As one venture capitalist told 36Kr:

“You waste months trying to identify which cities actually have money. You’re bounced between agencies, and nobody seems to have a final say.”

The view from within the government wasn’t much better. Without clear roles, fund managers duplicated efforts. Local officials set performance targets that clashed with fund mandates. In extreme cases, entire fund ecosystems became paralyzed—capital trapped in bureaucratic loops instead of reaching the market.

Market-driven GPs have little choice but to adapt—or fail. But for state capital to evolve, systemic reform is essential.

That reform is now underway. In early 2025, Beijing released a landmark policy document outlining 12 directives for improving public fund performance. At the top of the list: clarify fund roles and mandates. The document also called for stricter classification, coordination between entities, and the elimination of duplication—laying the groundwork for a more rational fund lifecycle, from launch to exit.

Its underlying message was unambiguous: every fund must serve a distinct function. Those that don’t will be consolidated or phased out.

Some local governments are already moving ahead of the curve.

Specialization at scale

BSCOMC is leading one of China’s most methodical experiments in fund specialization: a family of eight industry-specific guidance funds, collectively totaling RMB 100 billion. Each fund is dedicated to a distinct vertical, reflecting a deliberate effort to move beyond one-size-fits-all public capital deployment.

Once the strategy was finalized, BSCOMC allocated the funds across Beijing’s districts and appointed best-fit general partners (GPs) for each theme. The portfolio includes:

- Shoucheng Holdings (robotics).

- Legend Capital (IT).

- Qiming Venture Partners (AI).

- CBC Group (biotechnology).

- CoStone Capital (advanced manufacturing).

- Zhongguancun Development Group (new materials).

- Fortune Capital (aerospace and low-altitude economy).

- BAIC Capital (green energy and sustainability).

The results so far have been promising. As of late 2024, BSCOMC deputy general manager Guo Chuan reported that the eight funds had made 167 investments totaling RMB 17 billion (USD 2.4 billion), achieving 120% of the year’s deployment target.

Notably, nearly 20% of the deals involved inbound relocation projects, underscoring the funds’ “magnet” effect in reinforcing Beijing’s industrial base.

Consolidation as reform

In early 2024, Shanghai launched a sweeping overhaul of its public investment system aimed at reducing duplication and redirecting resources toward higher-priority strategic goals.

At the center of the reform was the merger of two major state-owned entities: Shanghai State-owned Capital Investment (SSCI) and the Shanghai STVC Group. Though both operated under the city’s state asset regulator, they had long maintained overlapping roles in fund management, industrial support, and strategic equity holdings. The result was fragmented resources, blurred responsibilities, and inefficient capital deployment.

Shanghai’s leadership tackled the problem head-on. In an interview with Jiefang Daily, Shanghai SASAC chief He Qing noted the city’s goal to “coordinate fund governance and define functional roles across private equity structures.”

The consolidation was made official on April 16, 2024. Following final approvals, SSCI absorbed STVC Group, creating one of the largest local government capital platforms in the country. Together, they now manage over RMB 140 billion (USD 19.6 billion) in assets and oversee a fund portfolio totaling RMB 170 billion (USD 23.8 billion).

Under the new structure, SSCI focuses on strategic equity investments and high-level capital operations—managing both parent funds and direct industrial stakes. STVC Group, now a second-tier subsidiary, concentrates on early-stage innovation and emerging tech sectors.

Observers see the merger as a potential pilot for one of Beijing’s core 2025 policy directives: “optimize and consolidate existing funds.” If successful, it could offer a playbook for other cities grappling with bloated, redundant fund ecosystems.

Shenzhen: Four platforms, one playbook

Shenzhen’s state capital system stands out as one of the most intricate examples of top-level coordination in China. Over decades of incremental reform, it has evolved into a mature yet dynamic structure—shaped by shifting policy priorities and market demands.

The city is home to four major state-owned capital platforms, but two are most directly involved in equity investment: SCGC and SIH. In broad terms, SCGC has traditionally focused on early-stage startups, while SIH has leaned toward mature-industry consolidation and strategic capital deployment. Yet over time, the functional boundaries between the two have increasingly blurred.

SCGC was founded in 1999, and much of its history is well-documented. Two pivotal moments, however, mark turning points in its institutional development.

The first came in 2004, when Shenzhen’s SASAC appointed Jin Haitao—then deputy general manager of SEG Group and general manager of SEG Stock—as SCGC’s chairman. Around the same time, SCGC transitioned from a president-led model to a chairman-led structure. Its first two chairmen, Wang Suiming and Li Heihu, were both veterans of the original Shenzhen Investment Holdings, foreshadowing future convergence between the two entities.

That same year, following an in-depth study of the Temasek model, Shenzhen SASAC restructured SIH by merging it with two of its asset management units in commerce and construction. This marked the beginning of a two-pronged strategy: SCGC would remain focused on innovation-driven, early-stage equity investment, while SIH would concentrate on integrating mature assets and deploying strategic capital.

The next major milestone came in 2018, with the launch of the Shenzhen Angel FOF. City officials announced that the new vehicle would be co-managed by both SCGC and SIH. At the time, SIH already controlled several equity-focused entities such as Shenzhen HTI Group and TopoScend Capital. The joint stewardship of the FOF signaled a deeper integration between Shenzhen’s early-stage and strategic investment functions, ushering in a more unified capital ecosystem.

This evolution illustrates a critical lesson: for a municipal SASAC managing trillions of renminbi in non-innovation assets, adaptability to market dynamics and innovation trends is no longer optional—it’s essential.

Walking the tightrope

State capital has always faced a core contradiction: the obligation to safeguard public assets—and the necessity to embrace risk.

After all, venture capital is built on the premise of venturing into the unknown. And innovation rarely flourishes without uncertainty.

For public LPs aiming to catalyze tech ecosystems, the biggest shift is more philosophical than procedural. It entails learning to respect the market, even when that means accepting failure. That requires giving fund managers more autonomy, aligning incentives with long-term outcomes, and—critically—relinquishing control when needed.

Several regions across China are now charting that course.

Futian’s trust-first model

Located in Shenzhen’s Futian district—widely seen as the financial heart of the city and a birthplace of Chinese venture capital—the Futian Yindao Fund stands as a benchmark for market-oriented public capital.

In 2003, Futian became the first locality in China to introduce dedicated regulations for the VC industry. Since then, its flagship public fund has evolved into a model for how local government capital can align with market dynamics.

According to Hurun’s 2024 “Global Unicorn List,” the fund and its network of sub-funds have backed 122 unicorns globally, which is an extraordinary number for a municipal-level LP.

Yet Futian’s greatest contribution isn’t just capital. It’s trust.

As Fosun Health Capital CEO Li Fan put it:

“Futian’s strength isn’t just the capital—it’s the system. The government only exercises veto power over compliance. They don’t interfere in the investment decision.”

That philosophy has translated into real policy innovation. In December 2024, the fund became the first government-backed LP in China to formally embrace the concept of “patient capital,” announcing a blanket two-year extension for all sub-fund durations to better align with long-term investment cycles.

As of November 2024, Futian had backed 51 funds with a combined scale of RMB 160.4 billion (USD 22.5 billion).

Its LP selection strategy has evolved in four phases:

- Local champions, such as SCGC, Fortune Capital, and Green Pine Capital Partners.

- High-return market leaders, regardless of geography.

- Corporate VC funds, backed by listed companies that provide exit and acquisition pathways.

- National policy funds, provided they establish operations in Futian.

Critically, Futian’s LP agreements impose minimal hard terms that are primarily sector alignment and a 50% reinvestment ratio. Aside from basic compliance checks, investment discretion is left entirely to the general partners.

The result: one of the most agile, GP-friendly public capital platforms in the country.

Letting managers own the upside

In theory, government capital has unlimited patience. In practice, it often struggles to attract and retain top-tier investment talent—especially when compensation is tethered to public-sector pay scales.

That was the challenge Jiangsu faced with its flagship state-owned investor, Govtor Capital (also known as Jiangsu High-tech Investment Group). As chairman Xu Jinrong once remarked:

“In the market, people doing what we do earn RMB 5–10 million (USD 700,000 to USD 1.4 million) a year. We earn RMB 300,000–400,000 (USD 42,000–56,000).”

The solution? Mixed ownership and aligned incentives.

In 2014, it established Addor Capital as a fully marketized investment platform. Govtor holds 35% of Addor’s equity, while up to 65% is owned by members of the management team. This structure gives investment professionals access to not just management fees and carry, but also co-investment opportunities—aligning personal incentives with fund performance.

By 2023, Govtor managed over RMB 120 billion (USD 16.8 billion) in total fund assets, spanning government guidance funds, market-based funds, and specialized industry vehicles, making it one of China’s largest provincial-level venture platforms. Addor Capital remains its best-known arm.

But the reform wasn’t just about profit-sharing. It was also about reducing risk aversion.

SND, a local investment group, noted in an interview that Suzhou New District explicitly offers “due diligence immunity” for state-backed equity investments. Without it, investment managers might hesitate to engage with high-risk, early-stage ventures for fear of personal consequences.

Meanwhile, new collaborative models are emerging. TopoScend Capital in Shenzhen—co-founded by SCGC, CDF-Capital, and Haier—has pioneered a tripartite structure that brings together government guidance funds, market-based fund managers, and industrial partners into a unified investment platform.

Xiamen: Small city, big discipline

Xiamen C&D Emerging Industry Equity Investment is a specialized arm of Xiamen C&D, focused on minority equity stakes in innovation-led sectors. While Xiamen itself is neither a major financial center nor a manufacturing powerhouse, C&D has built a credible investment track record by leaning into its strengths and avoiding its structural limitations.

One early success came in 2002, when C&D participated in a capital increase for Xiamen Airlines. As both the aviation industry and China’s broader economy grew, the deal generated outsized returns, setting the tone for C&D’s investment strategy.

To date, the investment platform has committed to over 70 funds, backing more than 800 companies. It frequently co-invests with top-tier GPs such as Legend Capital, China Renaissance, and Qiming Venture Partners, and has supported 37 IPOs—including Bloomage Biotech, MicroPort, and Titan Scientific.

Its core sectors include healthcare, TMT (technology, media, and telecom), and consumer, with portfolio highlights such as Mango TV and Bajiuling. This focus reflects a strategic decision: target lighter, innovation-led industries where capital can punch above its geographic weight.

As general manager Cai Xiaofan put it at a recent forum:

“In most sectors, it’s possible to achieve both market-based returns and meaningful support for industrial development.”

Respecting the market also means trusting market-based GPs. Over the past decade, C&D has backed more than 60 fund managers including Cathay Capital, Gaorong Ventures, Source Code Capital, and Centurium Capital, with 20 maintaining long-term partnerships of five years or more.

Wang Wenhuai, who chairs the platform, said:

“Venture capital is different from what we used to do. Our early investments were mostly in industry, and we weren’t as experienced in tech or innovation-led deals. So, we started by investing in GPs. We became an LP. That’s how we quickly learned the space—by watching how the GPs invest.”

One example is the Mango Wenchuang Fund, C&D’s most strategic partner in the media and culture vertical. Notably, C&D imposes no restrictions on fund registration or reinvestment quotas, and places no additional demands—earning it a reputation among managers as the “ideal LP.”

As Wang summed up:

“Market-based fund-of-funds, when combined with Chinese characteristics and professional LP management, are a cornerstone of the venture capital ecosystem.”

Suzhou’s co-investment model

If the so-called “Hefei model” is defined by top-down conviction and bold, centralized bets, then the “Suzhou model” represents a more collaborative, ecosystem-driven approach to capital deployment.

At the heart of this model is a co-investment structure: local government guidance funds partner with venture capital firms to launch joint sub-funds. These vehicles bring market-based GPs into Suzhou, who in turn invest in local startups—fueling industrial development from the bottom up.

The model’s most emblematic institution is Oriza Holdings, majority-owned by the Administrative Committee of Suzhou Industrial Park, with minority investment from Jiangsu Guoxin Investment Group. Oriza manages a suite of specialized funds, including:

- Oriza Greenwillow, focused on Southeast Asia.

- Oriza Seed, for early-stage deals.

- Oriza Rivertown, for scale-up companies.

- Oriza Hua, for integrated circuits.

- Oriza FOFs, China’s first fully marketized professional fund-of-funds, co-founded in 2006 by Oriza Holdings and the China Development Bank.

What makes Oriza FOFs distinctly “market-oriented” is its operational philosophy: no reinvestment mandates, no interference in capital deployment, and just one simple rule—investee funds must be registered in Suzhou.

Often mistaken for a standard government guidance fund, Oriza FOFs in fact operates with market discipline. That autonomy is rooted in its founding logic. Back in 2006, Suzhou Industrial Park had reached a turning point. Its sole state-backed investment platform, Oriza Holdings, realized that direct equity stakes alone couldn’t scale industrial growth. The solution was to invite venture capital firms into the fold and let them lead, rather than control, the capital allocation. Oriza FOFs was built to serve that mission.

Since then, it has played an active role in attracting VCs to Suzhou by hosting roadshows, coordinating investment summits, and offering operational ease with no reinvestment quotas. The philosophy is simple: if the local environment is strong, capital will follow.

That thesis has proven correct. In recent years, Suzhou has hit critical mass. In the eastern district of Suzhou Industrial Park, the government launched Sandlake Fund Town, a dedicated fund services zone. By January 2023, it had passed official inspection by the Jiangsu Development and Reform Commission. Today, the town is home to 267 investment firms, 563 registered funds, and more than RMB 289.6 billion (USD 40.8 billion) in aggregated capital—surpassing the scale of many headline-grabbing government fund initiatives.

Boldness beneath the bureaucracy

In truth, China’s state capital system has never lacked boldness, or the stories to prove it.

In 1999, the chairman of Hunan TV & Broadcast Intermediary handed his assistant a RMB 100 million check with a simple directive: “Go to Shenzhen and start a venture capital firm.”

The company had just gone public and was starting to taste the fruits of capital markets. The chairman’s timing was inspired by rumors that China’s ChiNext—a Nasdaq-style growth board—was about to launch.

That assistant was Liu Zhou. The firm he founded became Fortune Capital, now one of China’s trailblazing RMB-denominated venture platforms. Liu, newly transferred and untested, took that mandate south and started building. But by 2001, the ChiNext plan had been suspended. For years, Fortune Capital operated in the red. Hunan TV & Broadcast tolerated the losses—until 2005, when the board moved to shut the firm down, preserving only a skeleton crew.

At the time, Liu was in Xiangshan, Beijing. On hearing the news, he spent two days writing what became a legendary “ten-thousand-word plea” to shareholders. The board relented—giving him one last year. In 2006, the firm exited its first deal: Coship Electronics, with a 40-fold return.

Then came Hefei, whose high-stakes rescue of Nio stands as one of the boldest moves in Chinese venture history. With Nio on the brink of collapse, the city stepped in with a RMB 7 billion lifeline. The risk was enormous—and unmatched.

Before that deal, Nio founder William Li had pitched 18 cities, all of which declined. Reflecting later, he said:

“Only the government was thinking long-term. No investment firm was going to save us.”

HCIH, established in 2006, began as a conventional local infrastructure financing vehicle. Its transformation began just two years later.

In 2008, when display panel maker BOE hit a rough patch, HCIH—backed by Hefei’s municipal leadership—made a bold move. Instead of offering a loan, as most local SOEs would have done, it took a direct equity stake. According to China Economic Weekly, HCIH ultimately invested RMB 47.8 billion (USD 6.7 billion) into BOE, exiting RMB 24.4 billion (USD 3.4 billion) and earning over RMB 23.1 billion (USD 3.2 billion) in profit.

“Back then, few local SOEs dared to invest through equity. Most would only offer loans, which are burdensome for companies. But we came in with equity and committed to rise or fall together,” HCIH’s Li recalled.

That decision set HCIH on a path few city-owned platforms have taken, defined by deep, transformative bets rather than passive financial support. It also laid the foundation for its now-legendary rescue of Nio 12 years later.

More broadly, it allowed Hefei to anchor two strategic clusters early: display technologies and new energy vehicles (NEVs). As of today, six major automakers—including JAC Motors, BYD, Nio, Volkswagen, Chang’an Automobile, and Ankai—operate in the city.

The boldness visible in these deals is only the surface layer. What lies beneath is more telling: a willingness among local governments to shoulder risk and responsibility in the pursuit of innovation and industrial transformation.

One journalist, after visiting Hebei, wrote:

“The more responsibility you’re willing to bear, the bigger the mission you’ll be able to carry—and the greater the success you’ll achieve.”

For every local government official now standing beneath China’s banner of tech, industry, innovation, and development, that reflection resonates more powerfully than ever.

KrASIA Connection features translated and adapted content that was originally published by 36Kr. This article was written by Guo Yunxiao, Huang Zhuxi, Xu Muxin, and Shi Jiaxiang for 36Kr.