Makoto Uchida could not have been clearer. Electric cars, the CEO of Nissan Motor said last month, would be a dominant theme for his financially battered company — with China leading the way.

The Japanese automaker was regarded as one of the early front-runners in commercializing electric passenger vehicles with its Nissan Leaf. Now, Uchida said at a news conference on May 28, electric cars would be something “to focus resources” on for its restructuring plan through fiscal 2023, after the company posted an annual net loss of JPY 671 billion (USD 6.2 billion).

By 2023 Nissan plans to launch more than eight new electric models — including the Ariya, hailed by Uchida as the “flagship of the new Nissan” for its advanced driving assistance technology — while cutting the number of models by 20%, compared to 2018. And Uchida expressed particular hope for China.

“China is highly receptive to new technologies, including connected car-like information technologies and electric vehicles,” he said.

Nissan is far from alone in continuing to bet big that Asian consumers will accelerate their shift into electric cars. Shortly after Uchida spoke, Volkswagen announced that it would invest EUR 1 billion (USD 1.1 billion) to take a 50% stake in the parent company of China’s state-owned Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group, or JAC Motors, and take control of its electric vehicle joint venture with JAC by raising its stake to 75% from 50%.

And Tesla, which became the best-selling new energy vehicle in China in May, said on May 8 that the US electric vehicle manufacturer has agreed with a Chinese bank for setting a credit line of up to RMB 4 billion (USD 565 million) to use for “continued expansion of production at Gigafactory Shanghai.”

But while these investments and plans express optimism in an electric-car filled future, the short term figures suggest consumers are not yet convinced.

China announced last week disappointing sales of new energy vehicles, including all electric, fuel-cell, and plug-in hybrid models, which declined by 23.5% to 82,000 units in May. This was despite a 14.5% annual growth in overall vehicles sales to 2.194 million units in China in the same month, bolstered by the government’s incentives.

In China’s case, the market has been dogged by government U-turns on subsidies for customers, which has hit consumer confidence. But nor is there any clear sign of expansion in other major markets such as Japan and India.

It contrasts with the situation in Europe, which has seen a surge in demand for electric cars, fueled by environmental regulations, even as manufacturers continue to expect that Asia will prove the better long-term growth market.

Analysts say that government incoherence over policies and infrastructure are sending a message that is deterring consumers — and leaving both governments and manufacturers at risk of falling far short of their targets.

“Governments’ subsidies have high uncertainty, although they are necessary to artificially lower the price of EVs to attract consumers. Multiple changes in subsidies may puzzle the market,” said Nobuhito Massimiliano Abe, at A.T. Kearney, pointing out that costly EV batteries are still uncompetitive on a market basis.

Calum MacRae, automobile analyst at GlobalData, also said a lot of consumers were confused by the variety of vehicles on offer. “Consumers can’t yet really discern where’s the best place for their cash in the middle of this market activity,” he said.

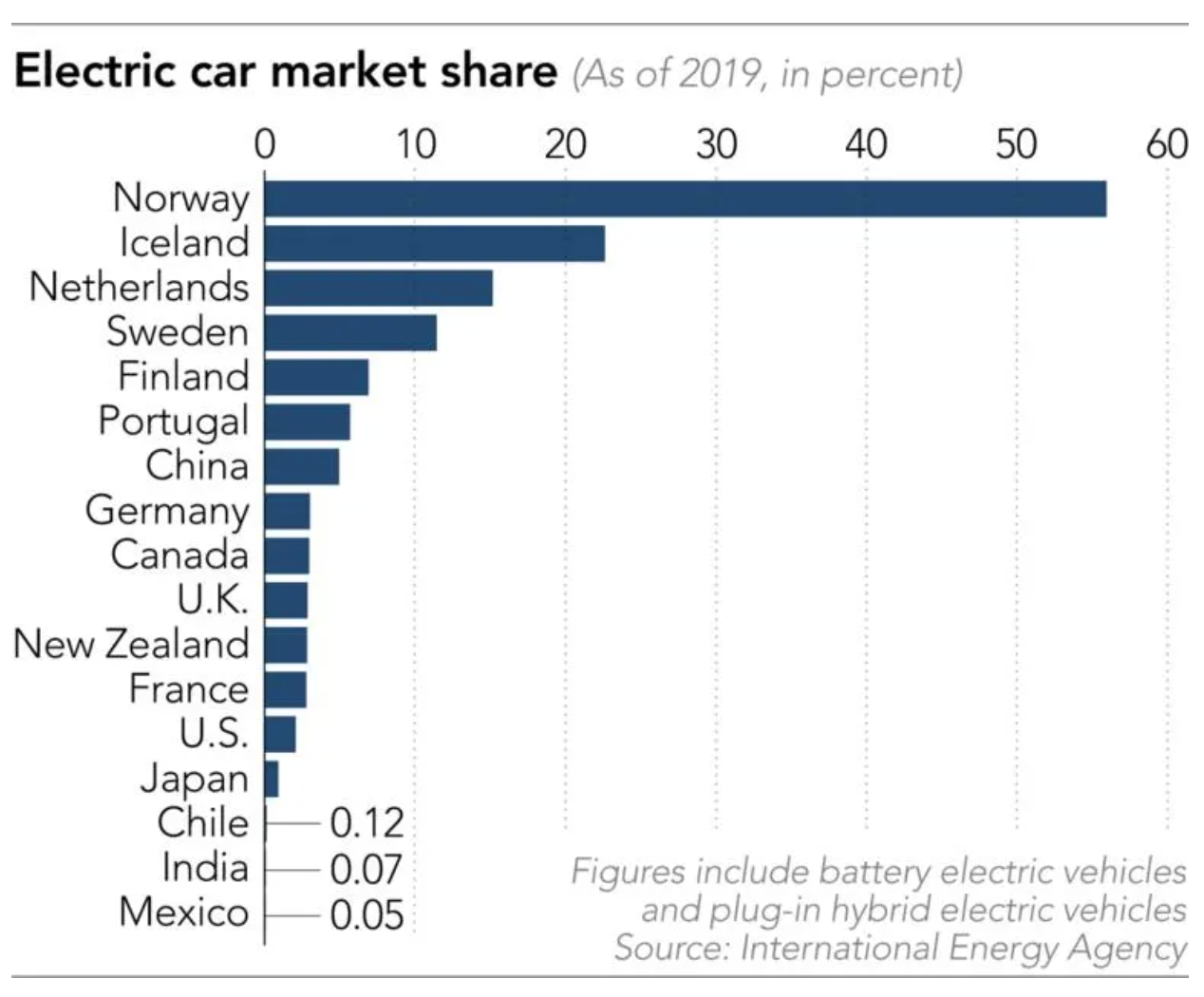

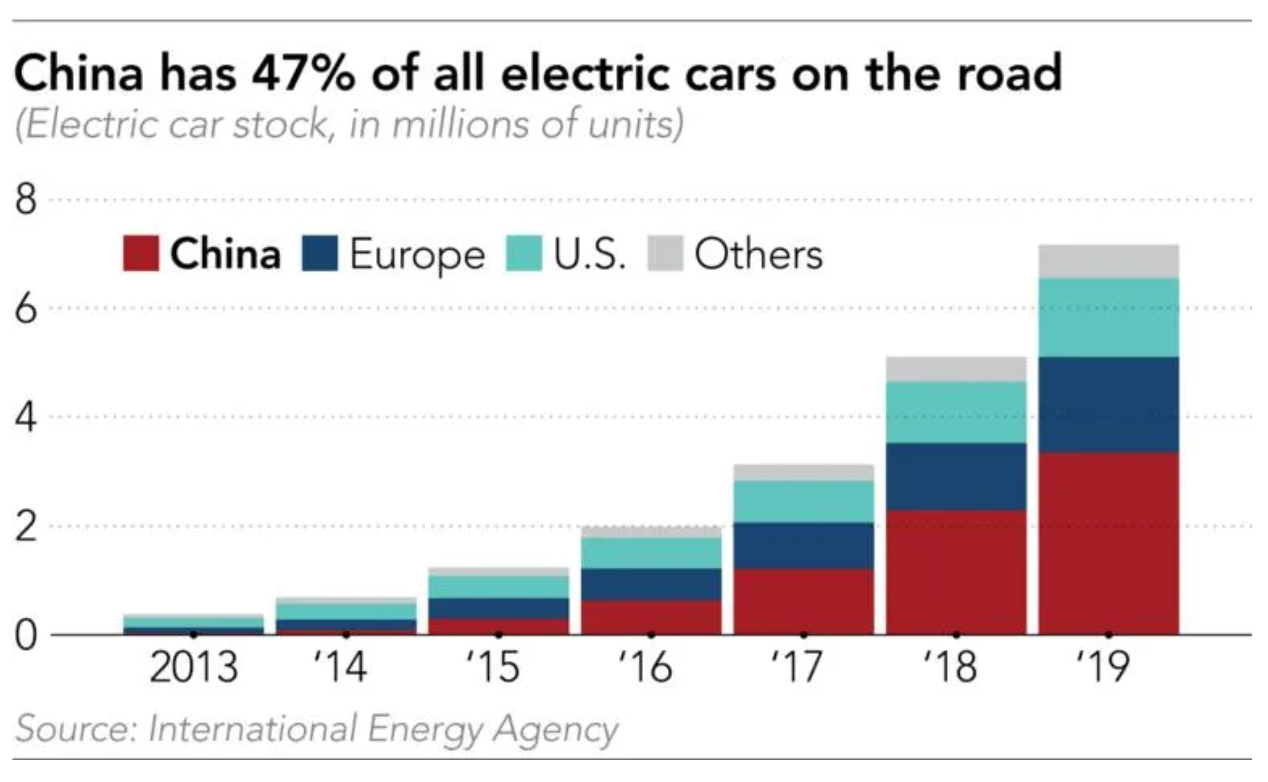

According to BloombergNEF, passenger global electric car sales jumped to 2.1 million in 2019, up from 450,000 in 2015. But electric cars’ share of total vehicle sales is still small: The research company expects it will account for 2.7% in 2020. China is the largest electric car market, accounting for 47% of electric car stocks worldwide, International Energy Agency data shows.

China wants electric, fuel cell, and plug-in hybrid vehicles to account for 25% of new cars sold by 2025, compared with nearly 5% in 2019. Fueled by the government’s massive subsidies, the Chinese electric car market saw at least 60 startups founded since around 2015. Tencent-backed Nio, sometimes described as China’s Tesla, listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 2018 and raised USD 1 billion.

But the government in 2019 reduced subsidies to electric car manufacturers by up to half, as incentives were regarded as jeopardizing their competitiveness.

Growth in the country’s market suddenly slowed down, and its new energy vehicle sales in 2019 dropped for the first time, slipping by 4% from the previous year to 1.2 million units. China’s BYD in 2019 faced “an unprecedented cut in government subsidies,” said the company, as its net profit for fiscal 2019 plunged 42% to RMB 1.6 billion. Nio in 2019 cut 2,000 jobs on the back of falling revenues, but secured a further RMB 7 billion of investment from several state-owned companies in April.

In response to the sudden drop in the market, Beijing in April announced a two-year extension of subsidies that otherwise would have been phased out by year-end. But the May figure suggests it will take time to lure buyers again, especially after the pandemic severely hit consumption.

“People would think: Will the government shift again on its policy, will it make incentives more generous in future, should I hold on before making a purchase?,” said GlobalData’s MacRae. “This causes confusion for consumers.”

Meanwhile, 18 countries in Europe posted a 57% increase in electric car unit sales between January and March compared with the previous year amid a broader plunge in car sales due to the pandemic. Electric’s share of overall car sales, accelerated by regulatory mechanisms, reached nearly 5%.

The European Union set rules for carmakers selling in the region to limit carbon dioxide emissions to 95 grams per kilometer from 2021, threatening multibillion euro fines if they did not. This contributed to the success of electric vehicles in recent years and the EU will toughen regulation further from 2030.

Elsewhere in Asia, however, there seems to be limited driving force to shift toward electric cars, with the potentially vast Indian market, like China’s, also unsettled by incoherent government policy.

In April 2019, the Indian government launched phase 2 of its Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles, or FAME, initiative. But high bars set for eligibility made it difficult for many manufacturers to meet the criteria, which included having lithium-ion batteries instead of more conventional lead-acid batteries. India, which had set a target to sell 100% electric cars by 2030, has now cut this to 30%.

Mahindra & Mahindra unveiled in February an SUV-typed electric car which only costs INR 825,000 (USD 10,900) with government subsidy, to cater to price-sensitive local tastes. “If there’s a cost issue in China it will be even more of a problem in India,” said GlobalData’s MacRae, implying that in a market with such low cost car ownership it is too early for mass take-up of electric vehicles.

A lack of battery charging stations is also a burden for the market. Maruti Suzuki, which has nearly 50% of market share in India, announced in fall 2019 that it would postpone a launch of electric car models scheduled this year. “It is not at the stage to launch them commercially,” said chairman RC Bhargava.

Manufacturers are also counting on growth in the electric car market in Japan, the world’s third-largest automobile market after China and the US Honda Motor will introduce a production line which allows assembly of electric cars and fuel-cell vehicles at the same time to prepare for their mass production.

But electric cars remain a long way from a significant position in the country, where the hybrid car market led by Toyota Motor has an important share. Electric cars, including plug-in hybrids, only accounted for 0.9% of total vehicle sales in Japan in 2019, according to the IEA, lagging behind China’s 4.9% and the US’s 2.1%.

As the region deals with the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, some in the car industry think it provides an opportunity for electric vehicles amid changing mobility habits and a greater appreciation of the environmental benefits.

“In urban congested cities in Asia, especially in China and India, there is room to adopt electric personal mobility,” said Moran Price, CEO of IRP Systems, an Israel-based startup developing electric powertrains for mobility. “When cities are in curfew we all had a chance to breathe clean air and see how it feels,” she added.

But while that may help to spur interest in electric vehicles, the economic effect of the pandemic — and its consequences for the finances of hard-pressed manufacturers — are a difficult headwind to resist.

“The pandemic had a massive impact on the economy, so consumers are even more unwilling to buy expensive cars including EVs,” A.T. Kearney’s Abe said.

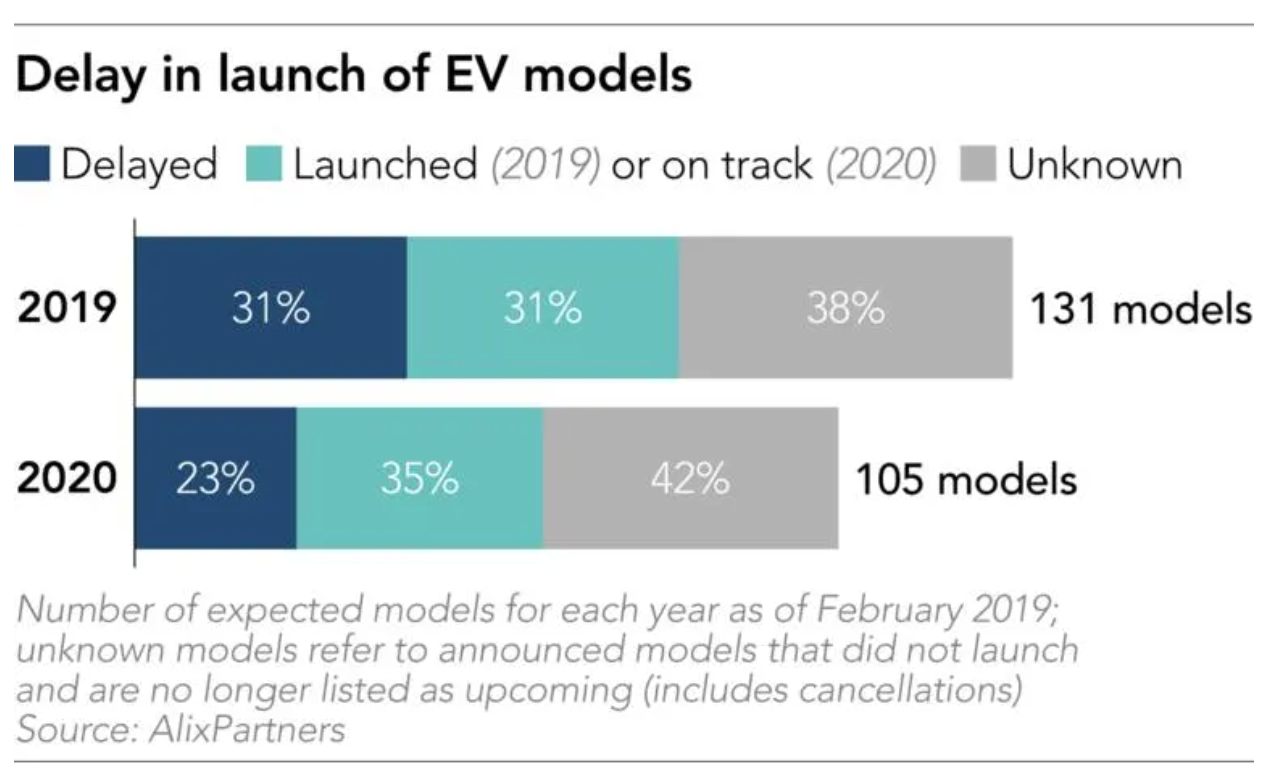

That could cast a lot of plans into question. “Many automakers will probably further delay the launch of new EV models after the coronavirus,” said Koichi Kawaguchi, managing director at consulting company AlixPartners.

Kawaguchi said the launch of 31% of 131 expected electric car models in 2019 was delayed. This year, already 23% of such models have been postponed — and models from China account for nearly one third of these new launches, he added.

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asian Review. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei. 36Kr is KrASIA’s parent company.