Recovering demand for cars should make this a great time to be selling to the automotive industry — but for a Japanese executive at an affiliate of one of the country’s biggest software developers, it is deeply frustrating.

The software he sells for cars is useless without computer chips to run it. And they are in an unprecedented shortage as a result of a surprise rebound in car sales coupled with a boom in sales of tech gadgets.

As a result it will take six months before his company — which suffered a slowdown last year in the coronavirus pandemic — can resume shipments to big suppliers in the car industry, the executive believes.

“The rebound from car companies ripples out first to suppliers and then to companies like us. Car companies were seeing rebounds from autumn, but chip production has not met this recovery pace,” the executive said. “We need to prepare for another challenge.”

This glum assessment is part of a worldwide problem. Serious shortages of automotive-related chips are prompting global carmakers to cut output, putting the brakes on their post-pandemic recovery.

Honda Motor is slashing production in Japan, North America, and China. Nissan Motor will be scaling down in Japan, while Toyota Motor will do so in the US. Ford, Volkswagen, and Daimler also join the list of automakers curtailing production. Big “tier one” suppliers to carmakers are also feeling the pinch.

The problem reflects how the coronavirus outbreak fueled demand from makers of consumer electronics, with PlayStation 5-led game consoles, laptops, and 5G smartphones racing off shelves.

But it also underlines the complexity of car companies’ supply chains, in which up to 30,000 parts can be required for a single vehicle. While automakers — so-called original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) — produce some components themselves, many other parts, from engines to seats, are provided by dozens or even hundreds of suppliers, which in turn need other suppliers for smaller inputs, including chips.

Dexin Chen, senior analyst at IHS Markit, said strong demand for automotive and nonautomotive chips is creating a shortage that could last about six months.

“This is a typical supply chain bullwhip effect, amplified by the concurrent high demands from other segments. … Our forecast is that it will be resolved by the second half of 2021,” Chen said.

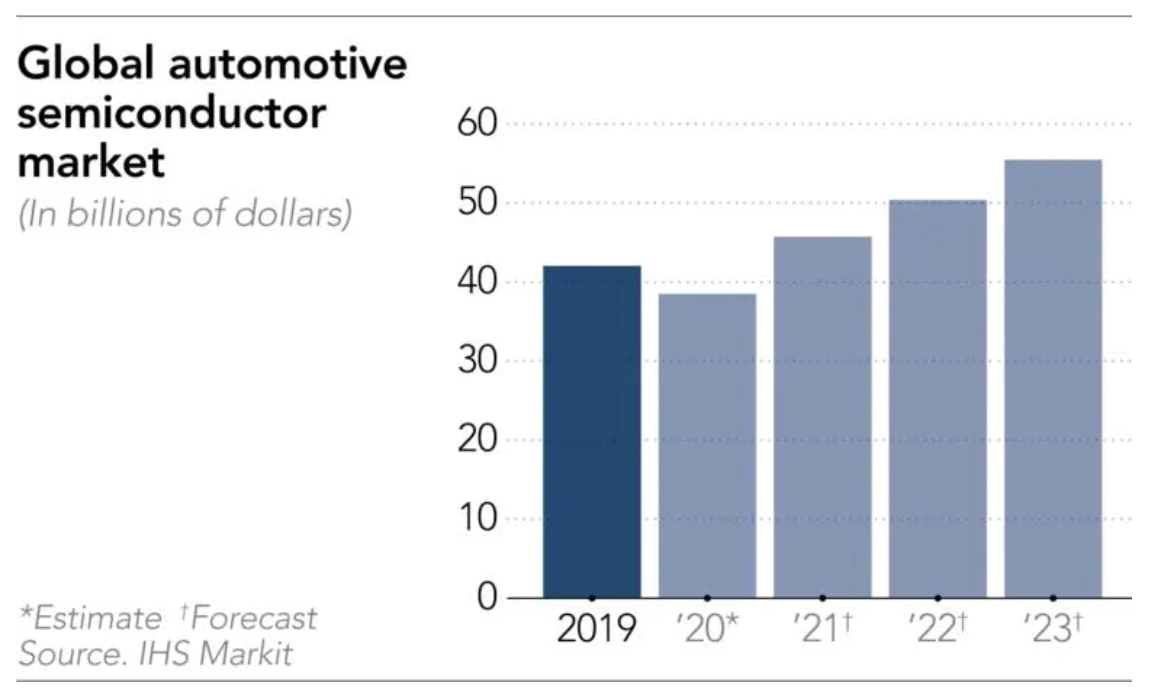

The risks of another chip crunch grow as the car industry moves through the transition to producing more autonomous and electric vehicles, which both need more semiconductors than regular cars. And together with new in-vehicle features such as advanced driver assistance systems, the car industry will only need more chips.

The value of the chips inside each car is expected to rise from USD 523 in 2020 to around USD 607 this year, according to Leuh Fang, the chairman and president of Vanguard International Semiconductor, a chip manufacturer affiliated with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. Vanguard’s customers include several global automotive chip providers.

According to IHS Markit’s automotive semiconductor market tracker, despite a big correction in 2020 due to coronavirus lockdowns, the automotive chip market will see a compound annual growth rate of 7.4% from 2019 through 2026 thanks to the transition to EVs and more electronic features in automobiles.

Experts say carmakers need to put more effort into coming up with a “plan B” list of alternative suppliers — learning lessons that were partly adopted in Japan after disruption caused by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

Manufacturers need to expand their “information-gathering” down the supply chain, identifying alternative suppliers “and bracing for production of substitutes when needed,” said Seiji Sugiura, a senior analyst at Tokai Tokyo Research Institute.

Among Japanese carmakers, “Toyota Motor has rebuilt its supply chain in a decade after the earthquake and suffers from the current shortage relatively less than European or US car manufacturers,” he added. A plant that Toyota relied on for semiconductors was destroyed in 2011, prompting Toyota to look for alternatives to the bottom of its supply chain, without needing to rely on factory-stored inventories.

On the other hand, Honda, which is cutting production of Fit vehicles in Japan this month, as well as five models in North America and nearly 20% of its production in China, will be significantly impacted, argues Koichi Sugimoto, senior analyst at Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities. He estimates that the automaker will cut its sales by 300,000 vehicles through March 2022 — mostly in China — assuming that the chip shortage lasts until around June. Honda sold 5.17 million vehicles in 2019.

Honda has a relatively higher dependence on foreign auto parts companies, Sugimoto noted. They tend to rely on foreign semiconductor developers, which outsource to contract chipmakers.

“Chip shortages are affecting our parts procurement,” a Honda spokesperson told Nikkei Asia, without giving details on the depth of the impact. “We are doing our best to minimize the impact by revising vehicle models and number of units to produce.”

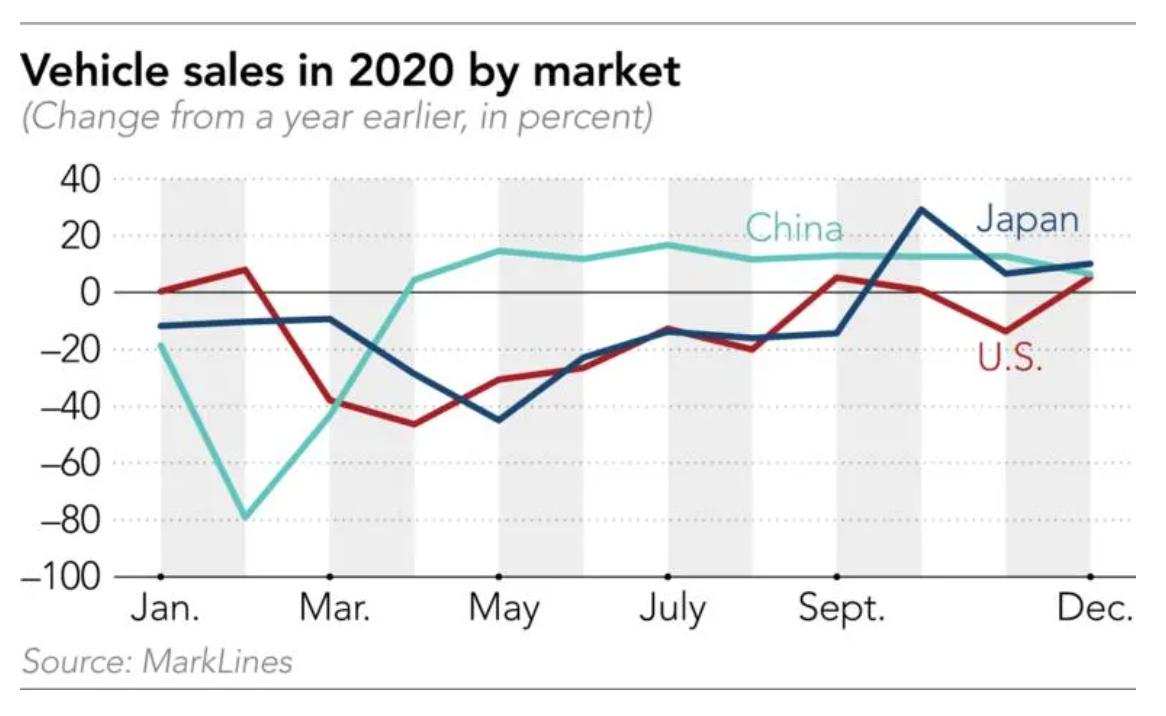

The origins of the chip crunch arguably lie in the way the car market was hit during the pandemic. Supply chain disruptions and plant lockdowns early in the COVID-19 outbreak were followed by sluggish sales that persisted for several months.

Moody’s forecasts that global sales of light vehicles plunged by 16% in 2020 from the previous year to 75.8 million units — a much sharper decline than the 9% downturn in 2008 after the financial crisis.

But recovery has been unexpectedly fast, led by China, where vehicle sales rose for a ninth straight month on an annual basis in December, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. In the US, General Motors reported a 4.8% sales increase for the fourth quarter, while Toyota posted a rise of 9.4% and Volkswagen a 10.8% increase. Auto sales in Japan have posted an annual increase since October.

This whipsawing has been mirrored in the market for automotive chips.

Lee Pei-Ing, president of Nanya Technologies, a maker of dynamic random access memory chips, said the automotive market showed only signs of recovery in the last quarter of 2020. “It’s not returning yet to pre-COVID levels, but it’s improving significantly. We expect demand will continue to recover,” Lee said.

A manager at a chip distributor told Nikkei Asia: “Automotive chip providers were quite conservative throughout last year, and they really didn’t want to have much inventory on hand. … When they finally saw demand coming back by the end of last year, they had very low inventories.”

But as the distributor points out, chip production takes time. A general power management chip, for instance, takes some 50 days, with another a week or two of packaging and testing processes before the product can be shipped. Automobile-grade chips, which have stricter safety protocols, can take even longer — and also need to go through another long automotive supply chain to be added to electric modules and other parts before car assembly.

So when most chip manufacturers started to negotiate with chip developers last September to understand needs for 2021, automakers and their suppliers might not have been aware of the prospects for a sudden pickup in demand.

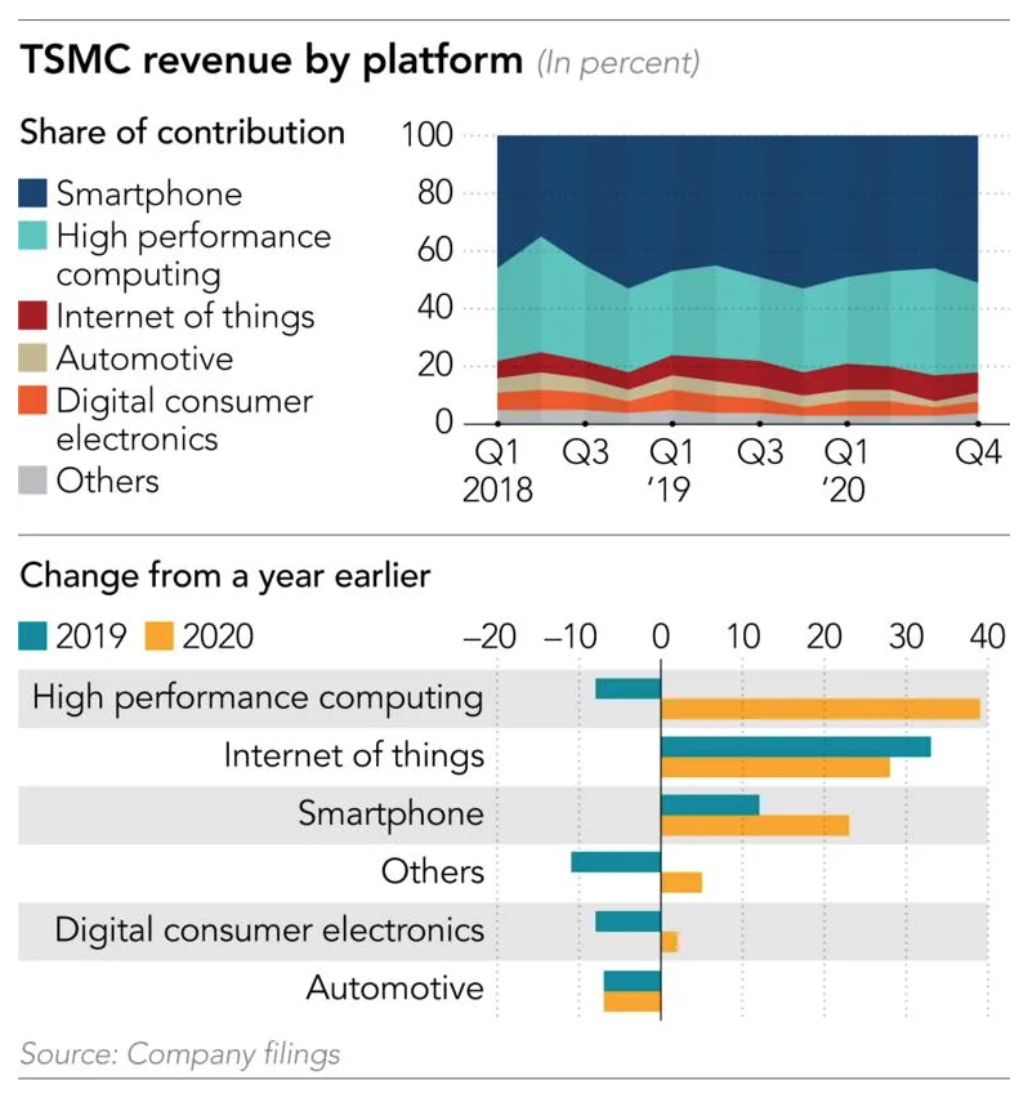

Rather, many tech executives say, automotive chip orders came in late last year and early this year. By that stage, the chip industry was already addressing robust demand for 5G smartphones, game consoles, laptops, and other items for the stay-at-home economy or for economic recovery.

TSMC, the world’s biggest contract chipmaker and a key production supplier to many automotive chip developers — from NXP and Infineon to Renesas Electronics and STMicroelectronics — said the company’s auto-related customers continued to “reduce orders” even in the July-September period.

“We only began to see sudden recovery in the fourth quarter. However, the automotive supply chain is long and complex, while many of our technology nodes have been tight throughout 2020 due to strong demand from our other customers. Therefore, in the near term, as demand from the automotive supply chain is rebounding, the shortage in automotive supply has become more obvious,” TSMC’s CEO, C.C. Wei, said on Jan 14.

The US-China trade and tech conflict also meant fewer semiconductors on the market because of Washington’s curbs on Chinese chipmakers. And the chip industry’s own development priorities have been another factor.

Another chip industry executive told Nikkei Asia that there has been barely any expansion for some mature chip process technologies and older factories over the past few years, despite increasing use of such chips. They are still often required in electronic devices alongside the more advanced chips that are increasingly the industry’s focus.

“People have been eyeing advanced chips for years, but all these cutting-edge processors also require power management chips and other periphery chips [for] the whole device to be functional,” the executive said.

A 5G smartphone needs two to three times as many sub-power management chips as a 4G smartphone, the executive pointed out. “People are expanding capacity for advanced processors, but people did not really expand capacity for [other chips].”

The result is a short-term scramble to secure chip orders.

“Everyone is fighting for capacity now,” another Vanguard International executive told Nikkei Asia. “A senior executive from a chip developer customer even flew to Taiwan and got quarantined for 14 days only to visit our boss briefly in person in the office to secure their production capacity for 2021. The move reflects how badly all these chip developers are trying to secure enough production for an economic recovery in the post-COVID-19 era.”

K.S. Pua, founding chairman of Phison Electronics, a provider of NAND flash memory controller chips and modules to both the consumer electronics and industrial and automobile markets, said there is no reason to be pessimistic for 2021 as all economic indicators are rebounding, but the supply shortage is posing uncertainties for his company’s outlook.

“Whether we can meet our revenue target for 2021 will depend on whether we can secure enough production capacity from production partners,” Pua told Nikkei Asia. “Automotive market is one growing area that we will continue investing in, but it will only be in 2024 to 2025, when cars become a ‘real moving computer and server,’ that we will see cars needing even more chips and much wider ranges of chips.”

Even as the fight for chip supplies heats up, Vanguard International’s Fang said his company is concerned as to whether demand remains as strong as it appears.

“When there is a component shortage, people tend to book a much larger number of orders with suppliers to solve the issues. … Sometimes the record orders could be misleading. Tech companies need to be cautious whether those orders are really reflecting the real demand,” he said.

IHS’s Chen made a similar point: “It is not easy for chip manufacturers to expand capacity in a short turnaround. Considering the capital expenditure, they will be very cautious in expanding [for those chips] unless there is solid commitment.”

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.