Bom Suk Kim is still not mentioned in the same breath as Jack Ma as an Asian business hero, but his company — South Korea’s Coupang — has made one of the splashiest public debuts on the US stock market since Ma’s Alibaba Group Holding wowed investors in 2014.

On Thursday Coupang, the e-commerce company that over a decade has carved out a massive slice of South Korean retail, arrived on the New York Stock Exchange via a USD 4.6 billion initial public offering.

Shares opened more than 80% higher than the USD 35 offering price. By the end of its first trading day the company — which few outside South Korea have heard of — was valued at over $80 billion.

It is the biggest market debut in the US by a foreign company since Alibaba, which raised USD 21.8 billion. Like Alibaba, Coupang also has the backing of Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank Group.

But while Alibaba has a massive home market — China is the world’s second-biggest e-commerce market with a size of USD 1.8 trillion, according to Motaword — Coupang operates mainly in South Korea, which ranks sixth globally with revenues of just USD 74 billion.

And that is not the only issue facing Coupang. The company has yet to have a profitable year despite fast-growing revenues and is facing fresh scrutiny over labor conditions following the death of a delivery driver reported earlier this week.

All of that was set aside yesterday when Kim, a Harvard Business School dropout who founded Coupang 11 years ago and now serves as its CEO, rang the opening bell in New York.

“We’re here today because we focus on a long-term strategy, [a] long-term vision. We’ve had teams and shareholders who are aligned with that vision … We’ll continue to stay steadfast to that DNA,” the newly minted billionaire told Bloomberg in a televised interview the same day.

Coupang exceeded even its own expectations. It originally aimed to sell shares at between USD 27 and USD 30. But that was raised this week after the banks involved in the IPO — including Goldman Sachs, Citigroup and UBS — tested investor appetite.

The debut is also a big success for SoftBank. Its Vision Fund, which has invested USD 3 billion in Coupang, is the largest shareholder with a 33.1% stake that was worth around USD 27 billion at the end of the first day’s trading.

Coupang is part of a big revival for SoftBank and Son over the past 12 months, after the CEO lamented that the coronavirus pandemic was crushing his unicorns. Now he and Coupang are the beneficiaries of investor appetite for a story of accelerating digital commerce in Asia.

Other big shareholders include Greenoaks Capital Partners, based in San Francisco, with a 16.6% stake. Founder Kim is the No. 3 shareholder, at 10.2%. However, Kim maintains control of the company as his Class B common stock, with 29 votes per share, gives him 76.7% of voting rights. His stake was worth USD 11.1 billion at the opening price.

Before its blockbuster IPO, Coupang spent 11 years focusing on the little things to cultivate South Korea’s e-commerce market. Delivery staff, for example, knock quietly instead of ringing the doorbell when bringing diapers to avoid waking babies. More recently it has made a play for eco-conscious shoppers with reusable packaging that it also collects.

“I love that the deliveries come so quickly and in reusable eco-bags, so I don’t have to worry about harming the environment,” said Kang Yu-rok, a digital marketer.

These small touches along with rapid delivery times — its “Rocket Delivery” service promises delivery within 24 hours — have helped Coupang become the country’s biggest online retailer, boasting nearly 15 million customers out of a population of 52 million.

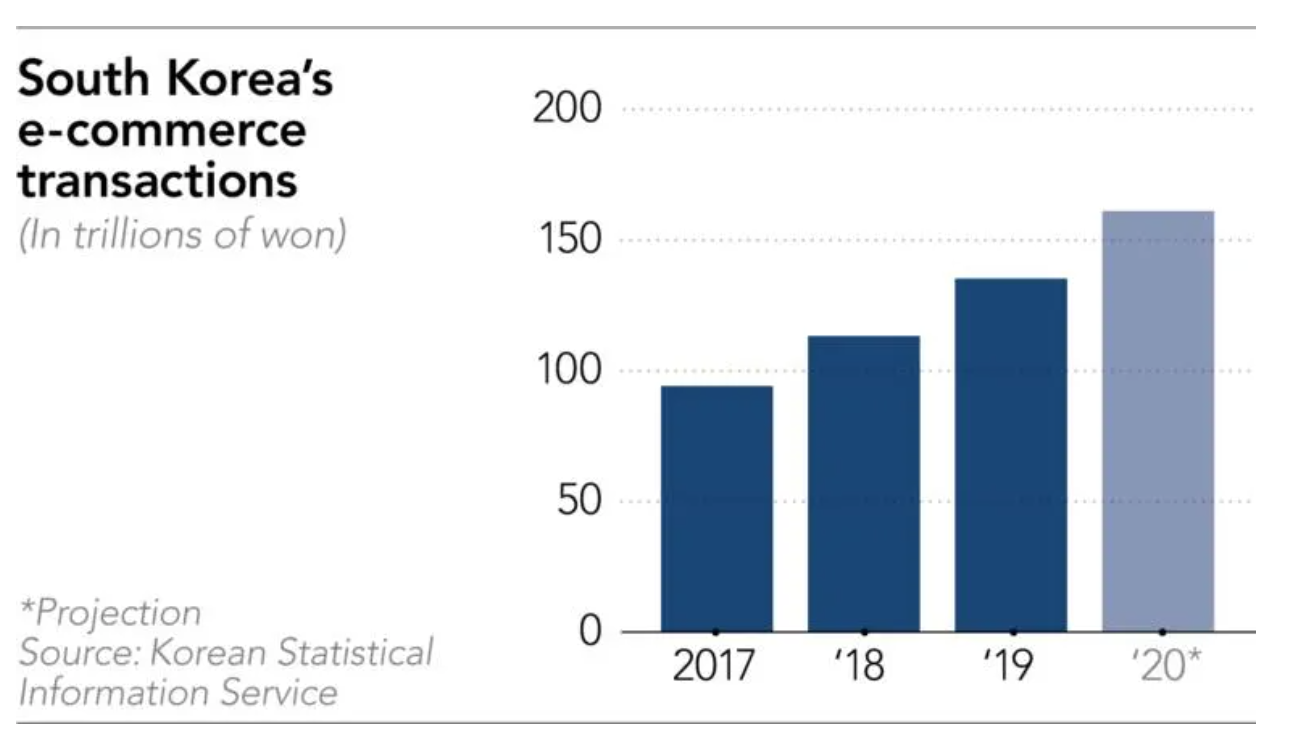

The company says South Korea’s e-commerce market is growing fast and that as the leader, it is poised to capitalize on this growth. Indeed, the country’s total online retails transaction reached 161 trillion won (USD 142 billion) last year, up from KRW 135 trillion a year ago, according to government data.

“COVID-19 drove purchase demand to online shopping, raising sales in almost every product category including foods and furniture,” said the Industry Ministry in its annual review of the retail market.

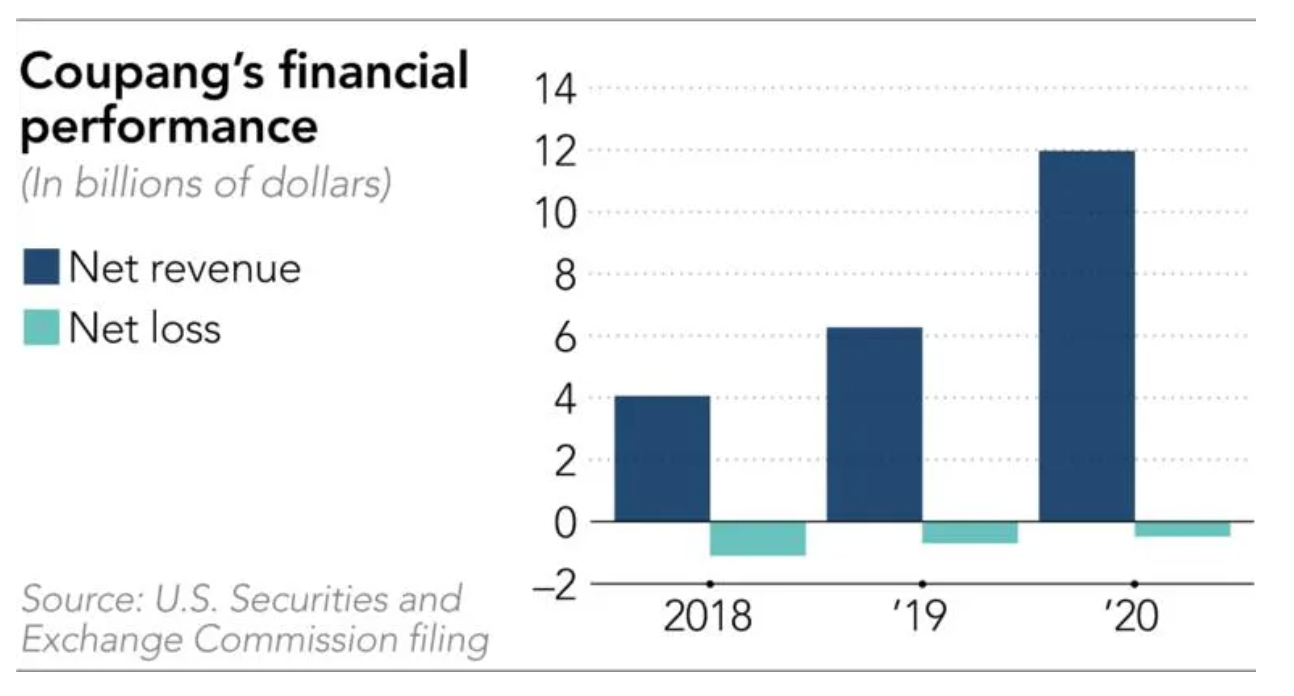

Coupang’s net retail sales outpaced that growth, nearly doubling to USD 11 billion from USD 5.8 billion during the same period. Net revenue per customer also increased to USD 256 from USD 161.

“That growth reflects our success in attracting, retaining, and increasing the engagement of our customers. In our experience, improvement in customer experience directly correlates with acceleration of customer engagement,” said Coupang in its securities registration before its listing.

But despite its large and growing revenues, the company has yet to make a profit. It logged a USD 527.7 million operating loss in 2020, slightly less than the USD 643.8 million the year before and around half its 2018 operating loss of USD 1.1 billion.

Analysts say persistent losses may not be a major issue for Coupang, as long as they continue to shrink.

“The value of online retailers is not determined by short-term profits, but by market share. In other words, it is revenue and customer traffic,” said Park Jong-dae, an analyst at Hana Financial Investment. “Operating losses do not matter as long as they are closing in on the break-even point. And Coupang is on this course.”

The company’s dominant market position — it controls 15% of the domestic e-commerce market — should also allow it to cut buying costs, Park said.

In fact, its financial performance is one reason Coupang picked New York for its IPO rather than the Korea Exchange in Seoul, which is reluctant to list loss-making companies. Other factors, analysts say, included founder Kim’s American citizenship as well as the presence of US and global institutions among its shareholders, most notably SoftBank.

“The Vision Fund led by Masayoshi Son played a big role in giving Coupang a good reputation in New York,” said Shin Jang-sup, a professor of economics at National University of Singapore. “Coupang is a case of a major global shareholder covering the weakness of a company. New York investors evaluated Coupang highly because they believe in the Vision Fund’s successful track record.”

But while the Son connection may have helped Coupang get off to a strong start on the New York exchange, the company still faces a fundamental issue: Its biggest strength — the Rocket Delivery system — is also a massive cost sink.

To achieve its trademark service, the company maintains more than 100 fulfillment and logistics centers in 30 Korean cities spread over more than 25 million sq. feet of facilities. Coupang spent USD 485 million on real estate and facilities last year, establishing its own logistics centers, according to CEO Score.

Coupang has defended its cost-heavy model, saying its massive infrastructure investments will pay off in the long term.

“We have made and will continue to make significant investments in our technology and infrastructure network to attract new customers and merchants. … These investments will be a key driver of our long-term growth and competitiveness, but will negatively impact operating margin in the near-term,” said Coupang in the form filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

And Coupang is not done beefing up its logistics infrastructure. The company said it plans to invest USD 870 million to build seven regional fulfillment centers over the next few years. It also said expenditures in South Korea for both infrastructure and workforce-related costs will exceed several billion dollars over the next few years.

Maintaining its own drivers and warehouses sets Coupang apart from rivals, who largely rely on outside logistics companies for deliveries. Naver, the country’s largest internet company, works with CJ Logistics for its e-commerce services. To strengthen the partnership, Naver bought a 7.85% stake in CJ Logistics at 300 billion won in October. eBay Korea offers its “Smile Delivery” service through logistics centers jointly run with CJ.

Coupang’s big spending to ensure rapid delivery is a calculated move to fend of growing competition. According to the Industry Ministry, there are 13 e-commerce players in the country, including foreign companies and the partnership between online retailer 11Street and Amazon.

Working conditions are another potential issue for Coupang. It has the largest directly employed delivery fleet in the country, consisting of over 15,000 drivers, while Naver and eBay contract this work out to CJ.

At least two recent deaths among Coupang workers, however, have raised questions over whether delivery drivers and warehouse staff are paying the price for such speedy service.

On Monday, labor groups reported the death of a Coupang delivery driver in his 40s, alleging overwork, a claim that the company denies. Last October, a worker in a Coupang logistics facility died after returning home from an overnight shift. A government commission later found the cause to be work-related.

Coupang is not the only tech company whose rapid growth has been accompanied by such controversy. Last December, a contract food deliveryman of Alibaba subsidiary Ele.me died while making his 34th delivery of the day.

For CEO Kim, this is just one of several challenges he will need to tackle if wants to become the next Jack Ma.

This article first appeared on Nikkei Asia. It’s republished here as part of 36Kr’s ongoing partnership with Nikkei.